IN SOUTHWEST NEW MEXICO

in the Old Southwest

THE SAN FRANCISCO RIVER BACKCOUNTRY – A PLACE WHERE THE MAGNIFICENCE OF NATURE AND THE LEGENDS OF THE OLD SOUTHWEST ABOUND

About 40 minutes north of Casitas de Gila Guesthouses there is a pristine, rarely-visited landscape hidden within the Gila National Forest of Southwest Catron County, where the essence of the Old Southwest awaits discovery for those intrepid seekers of roads and trails less travelled. This area, known as the San Francisco or Frisco River Backcountry, comprises roughly 200 square miles of rugged, highly-dissected mountains and mesas, bounded by US Highway 180 on the east and the New Mexico-Arizona state line on the west; situated between the San Francisco River and Little Dry Creek on the south; and the Blue Range Wilderness on the north. It is a timeless landscape, little changed from the times of the ancient Native American Mogollon Culture, who thrived here from early in the first millennium until around 1350, the subsequent replacement by the Apache Culture in the early 1600s, and the eventual arrival of Anglo pioneer farmers and ranchers in the late 1800s.

Throughout most of this area, the San Francisco River flows parallel to and within one or two miles to the west of US 180, bordered by broad river terraces suitable for farming, between the communities of Pleasanton and Glenwood and a few miles further north in the vicinity of the community of Alma. During the times of the Mogollon Culture, the San Francisco River served as a major north-south trade and travel route. Along those sections where the canyon widened, the trail linked numerous small villages that dotted the adjacent river terraces, which were extensively farmed for maize, beans, and squash. Convincing evidence from recent research suggests that the Spanish explorer Coronado led his expedition along this very same route in 1540, on his way north to search for the legendary Seven Cities of Gold or Cibola.

By the early 1600s, the nomadic Apaches, who had come down into New Mexico from the north, likewise travelled this same San Francisco River trail system extensively for over 200 years as it ran through the very heart of their vast new homeland of Apacheria. Then in the early 1870s, and much to the consternation of the Apache, the first wave of Anglo settlers began moving into the area to take up farming, ranching, and eventually mining.

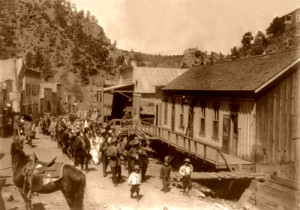

In 1876, Sergeant James Cooney mustered out of the Union Army and returned to the San Francisco River Backcountry to prospect a mineralized vein of silver, gold, and copper that he had discovered a few years earlier while on patrol chasing Apaches. The vein was located in a canyon in the Mogollon Mountains about eight miles east of the community of Alma. The vein proved to be of excellent value and by 1880 the thriving mining camp of Cooney on Mineral Creek was home to some 300 to 400 souls seeking their fortunes in the numerous mines and prospects or in three ore processing mills that now lined the narrow Mineral Creek Canyon. In time, the rich veins of ore in Mineral Creek were traced south into the adjacent drainage of Silver Creek. Here, the veins were found to be larger and richer, and by the late 1880s the mining town of Mogollon was founded, eventually boasting a population of 6,000.

At the same time Cooney Camp was booming, farming and ranching were coming on strong along the San Francisco River. Needless to say, the Apaches were not happy with this expanding intrusion into their homeland, and conflict soon erupted, most notably Chief Victorio’s attack on the Cooney Mine and Alma on April 28, 1880, and Chief Ulzana’s ambush of Federal troops at Soldier Hill on December 19, 1885, near the present day Aldo Leopold Overlook rest stop on US 180, about seven miles south of Pleasanton. Conflict with the Apache remained an ever-present danger throughout the 1880s until Geronimo’s surrender on September 4, 1886.

EARLY RANCHING IN THE SAN FRANCISCO RIVER BACKCOUNTRY

During the early 1880s, at the same time that the frenzy of prospecting and mining was intensifying in the Cooney and Mogollon District in the rugged mountains east of the San Francisco River, small farming homesteads and larger ranching operations were starting up throughout the San Francisco River valley. While there was grazing land east of the San Francisco River up to the front of the Mogoollon mountains, it was the land on the west of the river that caught the eye and imagination of these early ranchers. For here, they soon discovered, in the vast rugged mountains and mesa country west of the San Francisco River, were hundreds of thousands of acres of Open Range that were covered with rich virgin grasslands and in the Public Domain, just waiting for their long-horned herds. And, thus, during the 1870s, ’80s and ’90s large-scale cattle ranching came to the San Francisco River Country with the establishment of such historical operations as the SU Ranch, the Siggens Ranch, and the WS Ranch.

Much less is known about these early large-scale ranching operations than is known about what went on in the mining districts (Cooney Camp and Mogollon). Unlike the numerous local newspapers, mining reports, and various government documents that traditionally chronicled the development of these early mining towns and districts, the more isolated and solitary lifestyle of the ranchers and the wranglers that worked for them tended to leave a very short paper trail. And such is the case for most of the early ranching that took place within the San Francisco River Country, with one very important exception: the fascinating book: Captain William French’s book Some Recollections of a Western Ranchman, 1883-1899, New Mexico1.

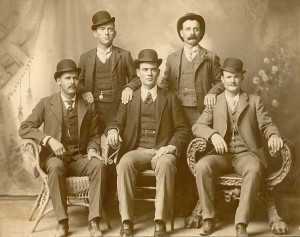

Captain William French was born in 1854 in Dublin, Ireland. He was an officer in the British Army from 1876 to 1882, attaining the rank of Captain before emigrating from County Roscommon, Ireland, on November 4, 1883 to the United States, where he soon became a partner in the expansive WS Ranch operation at Alma, New Mexico Territory. At that time the WS Ranch was owned by English interests and was grazing a vast area of Public Domain land that stretched from the San Francisco Hot Springs near Pleasanton, NM on the south, to Saliz Pass on US 180 on the north, and from the headwaters of Mineral Creek and Whitewater Creek in the Mogollon Mountains west to the Blue River in Arizona. Through French’s eyes and writing the early history of the San Francisco River Country comes alive in fascinating first-person detail. He tells it as he lived it, and he witnessed it all, from saloon shootings up at the mining camps at Cooney and Mogollon, to his transportation of the fallen soldiers from Ulzana’s Ambush at Soldier Hill back to the WS Ranch cemetery, to his professed eventual realization that some of the former wranglers that worked for a time at the WS Ranch included none other than the outlaw train robber Robert Leroy Oarker, alias Butch Cassidy, and possiby Harry Alonzo Longabaugh, alias The Sundance Kid, and probably several other members of the famous Wild Bunch gang.

THE SAN FRANCISCO RIVER BACKCOUNTRY’S BOOT HILL CEMETERY

The last three decades of the 1800s saw tumultuous times in the San Francisco River Backcountry as increasing numbers of homesteading farmers, miners, and ranchers moved into the area drawn by the diverse natural resources of this wild and rugged landscape. In many ways the area in those days was a microcosm of what was taking place throughout the American West. Clash of values, individual and group self-interest, and major cultural differences were inevitable, ubiquitous and unending. Homesteaders built fences, closing off water and good pasture, whereas ranchers demanded unlimited access to open public range. Miners demanded both the right to prospect and then develop mineral properties wherever they were found, unfettered by government regulation or interference. And then, of course, were the indigenous Apaches who considered this country their sacred homeland, and were simply defending it from the defiling invaders. Finally, add to this mix the individual lawless opportunists, scoundrels, outlaws, rustlers, claim jumpers, purveyors of desultory pleasures and other unsavory characters who followed the frontier developments, and you have a rather unstable mix that was subject to explosive events that could detonate at the drop of a hat.

Boot Hill cemeteries are a legendary staple in the traditional lore of the American West. Most commonly they refer to those particular havens of everlasting rest where persons—typically Alpha males—such as outlaws, gunfighters, drunken cowboys, gold-crazed miners, gamblers, etc., who died with their boots on after being shot, hung, stabbed, choked, or otherwise terminated, are interred. The term, however, can also refer to those who died in the pursuit of more honorable activities such soldiers, ranchers, farmers, or travelers who were killed or murdered simply because they happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. The small WS Ranch Cemetery located near Alma falls mostly, and possibly totally (as there being two sides to every story), in the latter category. All were men, all died violently, all were shot, and all died with their boots on . . .

In the same context that the San Francisco River Country can be considered a microcosm of what was taking place throughout the American West in the late 1800s, the WS Cemetery abides as a virtual time capsule chronicling the events and culture of the surrounding area during this same time period. Situated on the north side of a small hill on Gila National Forest land just of US 180 near Alma, New Mexico, the WS Ranch Cemetery today contains four tombstones commemorating seven burials, resulting from four separate traumatic events that occurred during the time that Captain William French managed the ranch from the mid-1880s to late 1890s.

According to Captain French, the first body to be buried in the cemetery was that of Edward W. Lyon, a young man whom French had met two years earlier on board the Royal Mail Ship Arizona during his move to the United States, who worked on the SU Ranch 35 miles to the north. Lyons had come down to Alma to pick up the ranch’s mail, and was killed by Apaches on his way back. His tombstone consists of a small, greatly-weathered and difficult-to-read marble stone topped with a cross. The stone is inscribed: EDWARD W. LYON, CLONHOLME? DERBYSHIRE ENGLAND, KILLED BY APACHES MAY 30 1885, AGED 25 YEARS

In his book, Captain French reports, “The poor fellow had evidently been reading his mail and was utterly oblivious to such a thing as an Indian when shot, for an open letter of his was picked up on the trail, evidently where he had fallen off his horse and a short distance from where his body was found. He had evidently crawled into shelter to die and the Indians took no further notice of him.”

The next burials took place on December 21, 1885, following the ambush of Troop C of the 8th US Calvary at Soldier Hill, seven miles south of Pleasanton, by the Apache Chief Ulzana and nine warriors on December 19, 1885. Four or five troops (accounts vary) and a surgeon by the name of Dr. Maddox were killed. On same day as the ambush, Captain French received a message at the WS Ranch sent by Lt. Samuel W. Fountain, officer in charge of C Troop, stating the following: “Troop ambushed on Dry Creek Hill. Maddox and five others killed. Would you kindly send up a wagon to help to bring up bodies.” Captain French complied and reports in his book the following: “As I walked back to the camp with Fountain that night he talked over the final disposition of the bodies, and expressed a wish to bury them in our little cemetery. He said that both Maddox and he had always admired its situation, and he was sure the poor doctor would like to be buried there, even if it was only a temporary resting-place. So it was arranged.

French further describes how two graves were dug following the return to the WS Ranch: a large mass grave for the soldiers and a separate temporary grave for Dr. Maddox, who would be subsequently returned to his family. He reports in great detail on the funeral ceremony, which he estimates was attended by nearly 200 residents of the local area.

Today, a single white government tombstone, erected in 1950, is found at the mass grave of the enlisted men killed that day. Inscribed are the names of four soldiers, two on each side. On the west side of the stone is inscribed: DANIEL COLLINS, MASSACHUSETTS, BS 8 CALVARY; GEORGE GIBSON, PENNSYLVANIA, PVT 8 CALVARY, DECEMBER 19, 1885, KILLED BY APACHES. The east side of the stone is inscribed: FRANK E HUTTON, ILLINOIS, WAGR 8 CALVARY; HENRY E MCMILLAN MICHIGAN PVT 8 CAVALRY, DECEMBER 19, 1885.

The next burial to take place was that of Charlie Moore, employee on the WS Ranch and friend of Captain French. According to Captain French, Old Charlie had a great interest in mining and invested heavily in numerous mining prospects in the area. In this regard he developed a friendship with a prospector he had grub-staked by the name of Mike Tracy. At that time, there was a saloon in Cooney operated by two men by the names of Penny and Shelton that Tracy was prone to frequent. As Captain French relates, it seems that this particular saloon had a bad reputation for getting patrons drunk, and then, having once relieved them of their money, beating them up and tossing them out into the street. After one unfortunate night of carousing, Tracy suffered this particular fate himself, and the next day went down to share his troubles with Charlie Moore. As Captain French confides “Charlie was not a man to be trifled with” and post haste went to Cooney with Mike to right the situation. After verbally confronting Penny and Shelton regarding the error of their ways, another afternoon and evening of drinking ensued with the ultimate result that Charlie was shot by Penny in the saloon. Upon hearing the news, brought by a messenger sent from Cooney, of Old Charlie’s demise, Captain French and others from the ranch rode up to Cooney. Appraised of the happenings by Uncle Billy Antrim (William H. Bonney’s, alias Billy the Kid, step-father), French succeeded in getting Penny arrested for murder and personally escorted him to Socorro where he spent a year in prison before being tried and acquitted by jury. Captain French remained forever convinced that Charlie had been murdered by Penny, as is clearly evidenced on the tombstone he bought and had inscribed and erected in the WS Ranch cemetery: CHARLEY MOORE, AGED ABOUT 60 YEARS, MURDERED AT LOVNEY [inscription error, should have been COONEY], OCTOBER 30, 1888.

The last burial in the WS Cemetery was that of Luke Flanagan, long-time Foreman of the WS Ranch and personal friend of Captain French. Flanagan had followed French to the United States from Ireland, where French relates his family had been tenants on French’s land for centuries.

The year of Flanagan’s death was 1899, and during these final years of the 19th century the winds of change were beginning to howl in Southwest New Mexico. With the surrender of Geronimo in 1866, the fear of Apaches raids ended, encouraging an ever-increasing influx of homesteaders, miners, and entrepreneurs into the San Francisco Country. The mines in the Mogollon District and neighboring Grant County were booming, with new discoveries being made every day. The standard gauge Santa Fe Railroad had reached Silver City in 1886, and on August 24 1889, the Silver City, Piños Altos and Mogollon Railroad Company was incorporated to build a railway north to Mogollon. At the same time, big changes were taking place in the vast surrounding lands of Public Domain.

In response to increased population growth, and the accompanying increased use, overuse, and in some areas abuse that was occurring within Public Domain Lands in the West, the Land Revision Act of 1891 gave the president authority to set aside and reserve parts of Public Domain land, wholly or partly covered with timber, regardless of whether it had commercial value or not. The first of these reserves was the Yellowstone Park Timberland Reserve established on March 30, 1891. During the next decade, millions of additional acres were set aside throughout the West during the Cleveland and McKinley administrations, including The Gila River Forest Reserve established by proclamation of President McKinley on March 2, 1899. Eventually, these early Forest Reserves would become part of the U.S. National Forest System.

With the establishment of these forest reserves and the probable inevitability of additional rules and regulations, the days of unlimited, unchallenged, and unfettered use of Public Domain lands were coming to an end, and Captain French was surely aware of it. Such legislation did not bode well for the future for the large operations such as the WS Ranch that, up until this time, had considered these Public Domain lands as their own private domain. In addition to the problems posed by the Forest Reserves, private land acquisition was increasing within the San Francisco River Country, greatly accelerated by Congress’ expansion of the Homestead Act of 1862 by the Desert Land Entry Act of 1877, which provided purchase of a section (640 acres) of Public Domain Land for $1.25/acre if the buyer irrigated within three years; and the Timber and Stone Act of 1878, authorizing settlers and miners to buy up to 160 acres of land with potential timber and mineral resources at $2.50 per acre. Natural water sources long used by the large cattle operations were being bought up and fenced off. Compounding these threats to large scale ranching, in 1889, the New Mexico Territorial Assembly passed an act to prevent the overstocking of ranges by limiting the use of Public Lands to the extent that livestock would be supported on by water to which the owner of the livestock had title.

All of these factors undoubtedly weighed heavily in the decision by Captain French and his partner Wilson in 1899, to purchase private land in northern New Mexico, near Cimarron in Colfax County, where it would be put into cultivation to raise alfalfa for the cattle. To accomplish this, French decided that his right-hand man, Luke Flanagan, would have to move there from the WS Ranch. On November 9, 1899, Captain French left for Cimarron by train from Silver City, leaving Flanagan behind to bring up French’s buggy and team.

On the same afternoon of Captain French’s departure, Luke Flanagan went up to Mogollon to say goodby and have a few drinks with some friends and pay off some bills. On the following day, a telegram from Silver City caught up with French just as he arrived in Springer, New Mexico. The telegram contained the news that Flanagan had been murdered and requested that he return. Devastated, Captain French immediately returned to Mogollon, where he found out that Flanagan had been shot in James Johnson’s saloon at the hotel by a man by the name of Saunders or Sanders (accounts vary) after a previous encounter that evening in Landerburgh’s Saloon. Saunders, a local man, had recently been appointed town marshall by the authorities in Soccoro, the County seat, to enforce a new town ordinance prohibiting the wearing of firearms within town limits. This new ordinance had resulted from complaints by the new owners of the Last Chance Mine who were, as Captain French puts it, “shocked at the Western habit of going about armed and the reckless manner in which they loosed off their guns on slight provocation”.

Accounts vary as to the exact sequence of events leading up to the shooting and how and why Saunders shot Flanagan, but apparently it had something to do with the gun that Flanagan insisted on wearing despite the ordinance. Evidence at the scene and witnesses accounts suggested that death came instantaneously to the unsuspecting Flanagan, as Saunders had shot him in the back of the head. Saunders had been arrested on the spot, and over the ensuing weeks, Captain French pressed charges for murder, engaged special counsel to assist the prosecuting attorney, and took care of bringing the witnesses to court in Socorro. But it was all in vain, for despite, in French’s words “the judge’s summing up practically told the jury that if they believed the evidence then they had no choice except to convict him”, the jury’s deliberation was short, returning a verdict of not guilty.

Much to the dismay of his family in Ireland, and despite a great effort, Captain French was unable to obtain consecration of Luke Flanagan’s gravesite. Having made an application to the padre in Silver City, French received the reply that it was outside his parish and jurisdiction, and that he would have to use a padre on the Rio Grande over 200 miles away. It seems that this padre would only visit the Alma area every four years, and by the time he did pass through again, Captain French had long since left the San Francisco River Country, having moved his ranching operation to the Cimarron area in 1900, and was by then living in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

As in the case of Old Charlie Moore, Captain French was convinced that Luke Flanagan had been murdered in Mogollon, as is indicated on the tombstone that be bought and erected: LAKE FLANAGAN [inscription error, should be LUKE], AGED 44 YEARS, MURDERED AT MOGGOLLON [inscription error, should be Mogollon], NOV. 9, 1899.

EXPLORING THE HIDDEN BACKCOUNTRY LANDSCAPE WEST AND NORTH OF THE SAN FRANCISCO RIVER

Traveling north or south on US 180 between Alma and the Gila/Cliff area one’s eyes are constantly drawn to the east to the magnificent towering front range of the Mogollon Mountains. Rarely is one’s gaze drawn to the west except for the occasional fleeting views of the San Francisco River where it closely parallels the highway, beyond which there is relatively little to catch the eye other than a mostly continuous and rather monotonous front of low, partially-forested mountains. But just as books shouldn’t be judged by their cover, the same holds true for the vast, fascinating landscape that lies waiting on the west and north sides of the San Francisco River, totally hidden from view by the low mountain front seen from the highway.

With the exception of a few small private inholdings near the San Francisco River and US 180, almost all of this hidden backcountry landscape is today part of the Gila National Forest. This is the Public Domain and Open Range land on which the cattle from Captain French’s WS Ranch and other nearby ranches grazed. Today, this vast area remains essentially unchanged since the pioneer days of the WS Ranch. Cattle still graze here, although the once Open Range has long since been divided up into large grazing allotments, bounded by rusting old barbed wire fences, which are regulated and administered by the Gila National Forest.

Roads are few and far between over this area, and those that are there are mostly rough gravel roads that generally require high clearance vehicles and are often rendered impassable during wet seasons. Most of these roads through this rugged landscape of forested mountains and intervening elevated rolling grassy mesas follow old cow, horse, and wagon trail routes established and used by the pioneer ranchers and loggers. With the establishment of the Gila National Forest some of these old cattle trails were eventually upgraded to official National Forest road status and improved to permit modern vehicular travel. In the last few years, some of these National Forest roads as designated and numbered on older maps of the Gila National Forest have been further upgraded, renumbered, and signposted as County Roads, which are now maintained by Catron County.

Access across the San Francisco River to this rarely visited portion of the Gila National Forest is limited. Only one bridge provides year-around access, and the few roads that ford the river require high clearance, almost always require four-wheel drive, and are only passable part of the year.

Close to the San Francisco River these County access roads are generally in fairly good condition. However, as one proceeds farther into this increasingly rugged and rarely visited terrain, the roads gradually become narrower and rougher, until the bone jarring and head snapping stage is reached were one begins to think maybe it’s a good time to turn around before the vehicle suffers something more than a cosmetic malfunction and help is a mere 20-mile-hike away. Part of the poor condition of these roads can be attributed to lack of use and less-than-frequent maintenance. However most of the roughness, or torture, as the case may be, is primarily due to the nature and composition of rocky terrain over which these roads pass. For this is volcanic rock country, consisting of a vast complex of mostly basaltic andesite and andesite lava flows which spread out from broad nearby shield volcanoes during the Late Oligocene to Early Miocene Epochs, between 24 and 29 million years ago, plus some occasional younger basalt flows that were extruded as the last gasp of volcanism in this part of New Mexico at the end of the Late Miocene about 5.5 million years ago.

GEOLOGY OF THE SAN FRANCISCO RIVER BACKCOUNTRY

The geology and geologic history of the mountains and uplifted mesas of the San Francisco River Backcountry differs significantly from that of the uplifted Mogollon Mountains and Gila Wilderness east of the San Francisco River. Separating these two uplifted areas is an essentially north-south trending valley averaging about six miles wide in an east-west direction. Between Alma on the north and Pleasanton on the south, the San Francisco River flows south along the western boundary of this valley.

In geological terms, this valley is what is known as a graben, which is a block of the Earth’s crust bounded on each side by high angle normal dip-slip faults that has subsided or moved downward vertically relative to the adjacent uplifted blocks of the Earth’s crust, which are called horsts. This particular graben is known in the geological literature as the Mangas Trench2, and is a major geologic feature that stretches southeast from Alma, through Glenwood, Pleasanton, Cliff, and Gila towards Silver City, forming a broad valley between the Burro Mountains on the south and the Mogollon and Piños Altos Mountains on the north. When driving north along US Highway 180 from Cliff and Gila towards Glenwood and Alma, one is driving up the middle of the Mangas Trench.

The Mangas Trench graben can be considered an elongated, subsiding, sedimentary basin which, over millions of years, has been filled with sediments that have been eroded and carried by streams flowing out of the uplifted mountains on either side of the trench. Over millions of years, these sandy and gravelly sediments can gradually solidify and become cemented into sedimentary rocks which can be mapped and named as distinct formations, such as the Gila Conglomerate which is found throughout the Mangas Trench.

The Mangas Trench is one of several similar basins in the area which began to form about 19 million years ago, during which time the Earth’s crust began to be stretched in an east-west movement, known as the Basin and Range Province extension, producing a landscape of alternating subsiding basins (grabens) and uplifted mountain blocks (horsts).

The vast uplifted area comprising the Mogollon Mountains and the surrounding Gila Wilderness east of the Mangas Trench and the uplifted mountains of the San Francisco Backcountry west of the Mangas Trench are both volcanic in origin; however, they differ markedly in composition, rock type, age, and manner of formation.

As described in the March 23, 2012 blog on the Supervolcanoes of the Gila Wilderness, the volcanic rocks found in the Mogollon Mountains and the Gila Wilderness were formed primarily by the eruptions of several large super-volcanoes which occurred in two time periods, the first around 34 ma (million years ago) and a second one around 29-28 ma. These eruptions were very explosive due to the high silica (SiO2 content 63-70%) of the magma which forms a highly viscous melt that does not flow easily. Owing to their highly silicic composition, the greatest volume of the volcanic rocks in the Mogollon Mountains and Gila Wilderness would be classified as rhyolite in composition with most of the material being violently ejected from the exploding caldera as pyroclastic ash that formed welded tuffs, rather than flowing out on the surface.

In contrast, the volcanic rocks of the San Francisco Backcountry are somewhat younger, mostly in age from 24 -29 ma with some very late extrusions of basalt which have been dated to 5.5 ma. These rocks are also quite different compositionally, since the magma that formed the volcanic rocks west of the Mangas Trench was much lower in SiO2 content (45-63%), resulting in a less viscous, more fluid melt that flowed easily from the various local volcanic vents, or that rose up along major faults to form sheet-like layers of volcanic rock ranging in classification from mostly andesite and basaltic andesite to occasional basalt.

The volcanic pyroclastic rhyolitic rocks of the Mogollon Mountains and the Gila Wilderness, while rich in the hard, chemically stable mineral quartz, are often poorly fused or cemented together, and somewhat porous. As a result they are structurally weaker, more susceptible to erosion, and are more easily worked by road machinery. In contrast, the andesite, basaltic andesite, and basalt volcanic rocks of the San Francisco River Backcountry are primarily composed of softer and chemically unstable minerals such as plagioclase, pyroxene, and amphibole silicate minerals. When freshly exposed these rocks are typically massive, dense, and hard, making the construction of roads a difficult undertaking. If, however, these silica deficient volcanic rocks, are exposed to the atmosphere and subjected to chemical and physical weathering over thousands of years, these minerals will break down through chemical and physical alteration to form a rich, clayey soil capable of supporting a dense cover of vegetation. This, then, is the origin and nature of the soils that cover much of the San Francisco Backcountry, where forested, rugged, low mountain highlands intersperse with broad expanses of nearly flat mesas covered by a lush growth of grasslands, the same land so greatly prized and grazed by the WS Ranch 130 years ago.

EXPLORING THE SAN FRANCISCO RIVER BACKCOUNTRY

To travel these old pioneer roads of the San Francisco Backcountry is to travel back in time to witness a landscape essentially the same as Captain French saw. It is raw nature at its finest where, depending on the time of the year, a wide diversity of animal and birds life can be observed in a variety of habitats ranging in elevation from 5,000 to 7,000 feet, from riparian forests of cottonwood and sycamore along the San Francisco River and its major tributary canyons, to ponderosa-lined mountain canyons, to vast expanses of upland mesa grasslands dotted with juniper and pinon.

For the photographer and the artist, it is a spectacular landscape offering endless vistas in all directions, as well as close-up nature studies. For the hiking enthusiast, the opportunities are endless, ranging from easy walks along rarely-travelled primitive roads across gently rolling grassy mesas to challenging hikes down into deep rocky canyons that flow into the San Francisco River. For the strong of heart, and even stronger of vehicle, the San Francisco River Backcountry is a great place to reconnect with nature and to explore and experience the New Mexico Territory of the late-1800s.

NOTE: The San Francisco River Backcountry is easily accessed from the Alma area by several gravel County roads that extend deeply, in some cases more than 20 miles, into this rugged portion of the Gila National Forest, some of which go all the way to the New Mexico-Arizona State line. While unlimited hiking is available over a variety of terrain, other than the County roads and the primitive forest tracks that lead off from them, there are no official, numbered Forest Trails. Consequently, visitors to the area are strongly advised to carry maps such as the new, 2013, Gila National Forest map or relevant USGS Quadrangle maps, plus, a compass or hand-held GPS if planning to hike off road.

Because of the rough condition of county roads and primitive forest tracks in this area, a high clearance vehicle is essential, and in some place 4-wheel drive is necessary. In wet weather, many of these roads become impassable for any vehicle due to the clayey gumbo soil that covers much of the area.

There are no sources of water available in this area, other than stock ponds and occasional springs and runoff in the deeper canyons.

As always, Casitas de Gila Guesthouses is happy to provide our guests with maps, detailed directions, current trail status and conditions, and updated weather information for any of the hikes or travels discussed in these blogs.

REFERENCES:

1. French, Captain William, 1928, Some Recollections of a Western Ranchman, 1883-1889, New Mexico, Frederick A. Stokes Co., New York.

2. Geology of the Late Cenozoic Alma Basin, New Mexico and Arizona (.pdf)