On September 2, 1877, the Apache Chief Victorio, a major leader of the Chihenne band of the Chiricahua Apache, and four other Chihenne chiefs — Loco, Nana, Mangas, and Tomaso Coloradas — fled the San Carlos Reservation in Arizona, along with some 300 Chihenne and a small band of Bedonkohe Chiricahua Apache1. They left the Reservation in an attempt to return to their ancestral homelands in New Mexico because of the unbearable conditions of disease (malaria), hunger, and mistreatment they had endured after being forced to relocate to San Carlos. Eventually, under Federal orders and escort, two thirds of these Chiricahuas, led by Chief Loco, did return peacefully to San Carlos in late 1878, but without Chief Victorio, who declared he would die fighting rather than return to San Carlos. Victorio hated San Carlos and considered the area known as Ojo Caliente his native land (close to what is now Aragon in Catron County, NM) and was determined to stay there. So strong was his love for this land that he was willing to pledge that “he would fight no more forever” if the government would allow him and his family and relatives to live there.

Over the next two years, acting through intermediaries, Victorio made numerous attempts to negotiate with the U.S. Government for the release of women and children family members and relatives who had been returned with Chief Loco to the San Carlos Reservation. Victorio’s proposal was that if his dependent family and relatives were released from San Carlos and brought to Ojo Caliente, he would agree to return to reservation life there and end the hostilities which he and his followers had engaged in since they fled the reservation. But these proposals fell on deaf ears within the Department of the Interior in Washington. After two years of endless conflict with Victorio and his band, the U.S. Government would simply have no part of it. There would be no reservation at Ojo Caliente, and Victorio would have to return to San Carlos. Finally, in late April 1880, his frustration and desperation having reached the breaking point, Victorio made his fateful decision: he and his warriors would go to San Carlos via the Mogollon Mountains and liberate his family and relatives. Victorio’s War was about to take a serious turn for the worse.

A decade earlier, in 1870, Sergeant James C. Cooney was on patrol as a scout for the 8th Calvary U.S. in the Mogollon Mountains when he discovered a mineral vein about 8 miles up a small creek (now Mineral Creek) in the mountains east of the Frisco Valley (now Alma), a few miles north of present-day Glenwood, NM. In 1875, Cooney mustered out of the Army and with a couple of partners, in 1876, started developing the claim that he had taken out on the vein he had found. By 1880, with the help of his brother, Captain Michael Cooney, and hired miners, their efforts had paid off, with the claim developing into a valuable silver mine, which, in turn, had attracted a number of settlers and other miners to the area.

It was late in the afternoon on April 28, 1880, just as the miners were quitting for the day, when Chief Victorio’s band commenced their attack on the Cooney Mine on what is now known as Mineral Creek. Three men were killed outright, and a fourth man, Mr. Taylor, his leg broken by an Apache bullet, was able to escape by hiding in a cave. The rest of the miners fled into the mountains where they hid until dark. Sensing the danger that the Apaches presented to the unsuspecting settlers down in the valley, Sergeant Cooney and a man by the name of Jack Chick courageously made their way down the Creek to the Frisco Valley, where they were able to warn the settlers. Heeding the impending danger, the settlers then gathered together at the Roberts ranch, where they set about converting one of the ranch buildings into a makeshift “fort”.

The next morning Sergeant Cooney, at the insistence of Mr. Chick, borrowed horses from the Roberts Ranch and headed back to the mine. A short time later the horses returned to the Roberts Ranch covered in blood, an eerie harbinger of what was soon to unfold …

A first-hand account of the details of what took place next on those fateful days at the Cooney Mine and the Roberts Ranch was recorded in 1937, as part of the WPA Federal Writers’ Project, in an interview with Mrs. Agnes Meader Snyder. Agnes Meader was in her early teens and had just recently arrived from Texas with her family to settle in the Frisco Valley when the attack occurred. At the time of the interview, she was considered to be the sole remaining witness to what is now known as the Alma Massacre (original WPA report). This interview, written down by Frances E. Totty, was part of the Folklore Project of the WPA Federal Writer’ Project, which was undertaken between 1936-1940. Her account is nothing short of riveting!

While it would be six long years after the Alma Massacre before the Apache Wars ended with the surrender of Geronimo, mining operations along Mineral Creek continued to develop without further incident. With the continued expansion of the Cooney Mine, plus the discovery of additional rich veins of ore nearby, the small conclave at Cooney Camp gradually evolved into a prosperous silver, gold, and copper mining camp. Eventually, at its peak around the turn of the century, Cooney Camp could boast to having a population of some 300 to 400 souls, numerous buildings, and various commercial enterprises supporting the mines. Unlike the feeling of isolation that one experiences when hiking up Mineral Creek canyon today, Cooney Camp was well connected to the outside world through regular service provided by wagons and other conveyances over a road that had been constructed along the Creek, up the narrow canyon from Alma. Additional veins of valuable ore continued to be found, with the result that by 1900 a significant portion of Mineral Creek was under claim and being prospected and mined. Three separate ore processing mills were in operation along the Creek, the largest being a 100-ton-a-day mill owned by the Mogollon Gold and Copper Company. But major change was soon to come2.

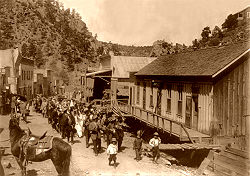

In time, the continued prospecting and mining of the ore veins along Mineral Creek revealed that the ore bodies continued to the south, out of Mineral Creek canyon, over the mountain and down into the adjacent Silver Creek drainage. Excitement grew when it was discovered that the veins there were more extensive and most likely richer than those along Mineral Creek. With this discovery, within a few years a new mining camp had sprung up, one that grew rapidly into the much larger town of Mogollon. By 1910, and the full potential of the Mogollon mining district understood, Cooney Camp was largely abandoned. Most of its buildings and mining equipment were dismantled and transported to bustling Mogollon, which was now growing by leaps and bounds. Within a few years, Mogollon had become a “real” town, sporting a theater, hotels, stores, numerous saloons and a school, all served by regular stage and freight lines out of Silver City. Soon, even the telephone and the new-fangled automobile made their appearance! At its heyday in the early 1900s, Mogollon was reportedly home to some 6,000 to 8,000 miners and their families, all seeking their fortunes from the numerous mining claims throughout the Whitewater Creek drainage.

But, as with Cooney, Mogollon’s heyday was short lived. Following the boom times during the 1920s and 30s, Mogollon, like Cooney Camp, simply faded away when the mines closed in the 1940s as a result of world war, the low price of gold and silver, and need for other, more strategic minerals. Today, Mogollon is essentially a ghost town, with only a handful of year-round residents. But, perhaps, when considering the current price of gold and silver, it is just quite possible that a new chapter in the history of Mogollon will be written and the old mines will once more yield their riches.

The histories of Cooney Camp and Mogollon overlap and are inseparably linked, an all-too-familiar story of many an evolving mining district in the Old West. Both have fascinating stories to share with the visitor to the area. In Mogollon the presentation is a more recent one, well preserved and accessible to all. Mogollon’s old mines, most of the original buildings, and the old graveyard are easily accessible by automobile or short hikes in magnificent mountainous terrain, and are just waiting to be explored. On weekends during the Summer and early Fall, visitors to Mogollon can enjoy a relaxing respite from their outdoor explorations and hiking with a nostalgic sojorn in a great little mining museum, a down-home gastronomic treat of excellent burgers, pie, and milkshakes at the Purple Onion Cafe and Heritage Center, a quiet interlude savoring the unique local arts and crafts at the Galloping Gourd Gallery, or an extended perusal of the eclectic offerings in the Antique Store.

Unlike Mogollon, however, the story of Cooney Camp is much more of a mystery. Who were these miners? Did they have families with them? Where did they come from? How and where did they live? In terms of actual years, Cooney Camp only preceded Mogollon by 20 years or so; yet when one visits the site it seems much, much farther back in time, as Nature has all but wiped away most signs of what was once a small but substantial and vibrant community. Starting with the systematic dismantling of almost all buildings and mining equipment down to their foundations and their subsequent removal to Mogollon, followed by numerous floods and forest fires through the years, not much stands out for today’s casual visitor to the area that would indicate the magnitude and intensity of the activity that took place there.

Nor is the written record much help. If one is willing to spend some time researching the history of Cooney, some documents, personal written accounts, and photos can be found3. But it takes some serious digging, and even then, after looking at the accounts, one is left with more questions than when they started. No, for the arm-chair historian, the story of Cooney is not to be found neatly and completely chronicled in some dusty old tome, but can only be gathered slowly in small yet tantalizing bits and pieces over a period of time.

For the seasoned and curious hiker, however, and a person who relishes the thrill of the hunt and the teasing out of well-hidden clues of times gone by in a spectacular, wild, and pristine setting, a hike up Mineral Creek to explore the overgrown remnants of the all-but-forgotten Cooney Camp offers a time-travel hike of intriguing and exceptional insight into the early pioneer history of the Mogollon Mining District.

ALMA AND THE MINERAL CREEK TRAIL

The small community of Alma, New Mexico, site of the Alma Massacre of 1880, is located about nine scenic miles north of the larger community of Glenwood on U.S. Highway 180. Upon reaching Alma (or the Frisco Valley, as it was called in 1880), not much has changed. The creek still flows amongst the ancient cottonwoods, and a few more modern structures can be seen. But that’s about all. Having read the Agnes Meader interview on the incident, it’s not hard for one to envision and relive the scene of the Massacre from the side of the highway before heading east up Mineral Creek for a hike to Cooney Camp …

Just as Alma’s only store comes into view, a signpost for Mineral Creek Road will be found on the right as one heads north from Glenwood, on U.S 180. Mineral Creek Road, which becomes Forest Road 701 upon entering the Gila National Forest, is a six-mile-long, county maintained, all-weather gravel road, suitable for all types of vehicles, that dead ends at the trailhead. About halfway to the trailhead, the road enters the Gila National Forest, and then passes through several privately-owned inholdings which are surrounded by National Forest. The no-trespassing signs that one encounters when passing through these private parcels are for the land on either side of the road. The road to the trailhead is a public right-of-way.

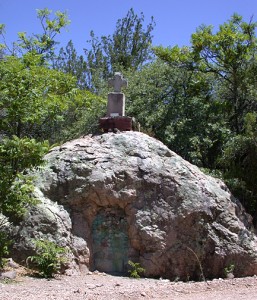

About 0.6 miles before the road dead ends at the Mineral Creek Trailhead, the road passes close by a huge boulder about 12 feet high on the right side of the road. This is Cooney’s Tomb. It was near here that Sergeant James C. Cooney and Jack Chick were ambushed by Chief Victorio and his warriors on April 29, 1880. It is here that Sergeant Cooney’s brother Michael and some miners blasted out a hole in the boulder for his coffin, sealing the opening with cement and ore from the Cooney Mine. A small pioneer cemetery is located behind the boulder, now known as Cooney’s Tomb. Be sure to visit the cemetery behind the tomb, too. Continuing on, the road ends at the trailhead. Here, a corral for pack horses using the trail, a small parking area, and a Forest Service kiosk marking the beginning of FT 701, the Mineral Creek Trail, will be found.

Forest Trail 701 up Mineral Creek to the old site of Cooney Camp follows the Creek closely, switching back and forth on both sides of the Creek, but never diverging more than a few hundred feet from the Creek itself. Most of the time water depth within the Creek is generally less than a foot and does not present a problem for the numerous 5 to 20 foot wide creek crossings that will be required. Higher water exceptions to this can sometimes be encountered during Spring runoff (with melting snow in high country during February or March) or during the brief flash floods that can occur during Monsoon Season (July through early September). Abundant boulders and downed trees in the Creek make dry crossings possible, and if you haven’t brought a walking stick with you, Mother Nature provides an ample supply of dead branches for such use whenever needed.

welded tuffs and flows in lower part of canyon

Within a quarter of a mile after leaving the Forest Service kiosk at the trailhead, the Time Travel hiker enters a spectacular, narrow slot canyon bordered by very steep to vertical canyon walls composed of horizontal layers of extremely colorful volcanic rocks, consisting of welded ash-flow tuffs, and rhyolite and andesite flow rocks. At the beginning of the canyon, the rocks exposed in the lower part of the canyon walls and the canyon floor consist of the Cooney Tuff formation, some of the oldest rocks in the Mogollon Range4. The Cooney Tuff is considered to be the oldest of the major caldera-forming ash-flow tuffs (ignimbrites) of the Mogollon Range5, which were deposited when the Mogollon Caldera6 erupted explosively some 34 million years ago during the Late Eocene or Early Oligocene Epochs of the Tertiary Period7. As one proceeds further up the canyon, successively younger rocks make up the canyon walls and the canyon floor such as the Fanney Rhyolite and Last Chance Andesite formations which were deposited during eruptions of the Bursum Caldera some 28 million years ago during the Oligocene Epoch.

Within a narrow stretch of the canyon an old mine entrance on the south side of the creek is soon encountered (now sealed with concrete because of safety concerns), the first of the many signs and remains of the numerous mines, prospects, and three ore processing mills that will constantly peak ones curiosity over the next two miles of trail up Mineral Creek. About a third of a mile in, the trail, which has been winding its way across a mostly sand and gravel creek bottom, gives way to solid bedrock filled with interesting stream-filled, circular potholes in the stream bottom. These holes are the result of the repeated cutting action that takes place over thousands of years when the colored, rounded pebbles and cobbles of rock one observes in the bottom of the holes get caught up in the churning whirlpool action of the rushing creek waters during flood stages.

(now sealed off)

A little further on, a small waterfall is encountered, below which are shallow pools of deeper crystal clear water. What a refreshing respite they offer on a hot day! Here and there, as one negotiates one’s way past the waterfall, the sharp eye will observe solid bars of iron sticking out of the rocks on the side of the canyon and the bottom of some of the pools. When and why were they placed here, one wonders? These bars, and many more like them that will be found along the bedrock portions of stream bottom upstream, are all that remain of a road that was constructed up the canyon from Alma to Cooney Camp, probably sometime during the 1880s. Proceeding upstream, one can only marvel at the pioneer engineering ingenuity, effort, and perseverance that was needed to construct this road; a road that saw the passage of hundreds of miners and their families on foot, on horseback, or by wagon or stage coach, plus huge lumbering, multi-mule team freight wagons loaded with massive, heavy equipment for the mines and processing mills. Today, little remains of this two-mile long, deep slot canyon road constructed my mule and hand labor. To build the road, the construction process began by first drilling holes into the solid bedrock on the side of the creek to hold numerous mining drill stem rods. Once securely anchored in the bedrock, these rods would serve to hold in place a massive platform of large logs which, in turn, would serve as a base for the thick layers of coarse rock, followed by finer gravel and crushed rock (tailings) from the mines used to finish the roadbed.

Thanks to M & H Castillas, guests from Texas,

for this photo!

Around the half-mile point, while passing through a somewhat wider, flatter and nicely wooded section of the trail, a mystery is encountered. Here, right next to the trail, a large brick-lined steel box is encountered, lying on its back with its open front gaping skyward through the trees. It takes a few minutes before one realizes that this is an old iron safe! Not only that, but with further examination it looks like, yes, the hinges and door have been blown off, definitely a long, long time ago! “What happened here?” one muses. Looking for other clues, one notices a little farther upstream on the other side of the creek the telltale regularity of an extensive retaining wall built of heavy stone. Could this be the site of one of the three ore processing mills that were reported to have existed along Cooney Creek? One crosses the creek to investigate further. Returning to the trail again one’s thoughts return to the mystery of the safe. Was this safe once housed in the mill office, perhaps to hold payroll or maybe gold concentrate? Why was the door blown off? Was the safe robbed, was the combination lost, or might it have just failed to open? Hiking onward, the immediacy of the trail fades, as these and other possible scenarios play out in one’s mind.

After another quarter or half-mile, one next comes to an another inviting rest stop – a broad, flat, grass-covered area with an absolutely huge apple tree rising in the middle. More signs of habitation are found close by: rusting pieces of discarded metal, a few rotting boards, a sagging wooden shed built into the side of the canyon, some stone foundations, the remains of an old outhouse, now all but fallen over.

A little further on the trail comes to an area on the south side of creek with more extensive foundations and more retaining walls. Climbing up on the flat terrace behind the retaining wall one comes to an arched brick and stone structure built into the hillside. Broken pieces of what appears to be an old cast iron stove lie outside the arched structure. What went on here, one wonders. Did it have something to do with ore processing or possibly a strong, dry structure for the storage of dynamite? storage area? And, if so, where was the source of the ore? Where were the mines? More mysteries.

It’s well past lunchtime now, but one decides to press on. Sergeant Cooney’s old mine can’t be much farther. And it isn’t. At about the two mile mark, one comes to it. Ahead, on the south side of the creek, one observes the discarded, broken rock of a mine dump cascading down from the upper vertical shaft high above on the canyon wall. Approaching closer, the looming, rusting hulk of the old boiler that provided the steam for the mining equipment, plus more retaining walls and part of a remaining stone wall of a mine building, come into view. Well aware of the extreme dangers of old mines, the gaping blackness of the creekside adit (horizontal mine tunnel) is observed temptingly, but not entered, for our hiker has heard far too many stories of the unfortunate tragedies of those who have ignored the warnings and met their demise in such situations. No, it’s much better to sit at the bottom of the mine dump, eating lunch, while picking through the broken rock in hopes of finding some azurite, chalcopyrite, or small pieces of discarded ore material. Did Sergeant Cooney’s pick dislodge this piece of ore, one muses before gazing up on the mountainside at what looks to be a small opening in the canyon wall. Focusing on the cave with binoculars, one wonders if perhaps that small opening could be the cave where Mr. Taylor, his leg broken by an Apache bullet, safely hid out when Chief Victorio and his warriors attacked that fateful afternoon on April 28, 1880 …

With the sun now beginning its downward slide in the West, one begins the two-mile return trek downstream. Still musing over the many mysteries and questions one has encountered this day, of one thing this hiker is certain … the Mineral Creek Trail is indeed a journey back through time.

REFERENCES

- Sweeney, Edwin R., 1919, From Cochise to Geronimo, The Chiricahua Apaches, 1874–1886, University of Oklahoma Press, 706 p. A very comprehensive, definitive, and thoroughly-researched book on the latter part of the Apache Wars. His earlier book, Cochise, Chiricahua Apache Chief, published in 1991, also by University of Oklahoma Press, tells the earlier half of the American Apache history.

- Rakocy, Bill, 1988, Mogollon Diary No. 2, Bravo Press. A very interesting history book concerning the early days of the whole Mogollon region, filled with old photographs, mining records, and personal accounts of people who lived and worked in Cooney Camp and Mogollon.

- Hoover, H. A., 1958, Early Days in the Mogollons: Tales from the Bloated Goat, Texas Western Press, 63 p. (out of print).

- An interesting early United States Geologic Survey Bulletin (787) written by Henry Gardiner Ferguson in 1927, which details the geology and ore deposits of the Mogollon Mining District.

- A downloadable report and geologic map done by the United State Geological Survey and the New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources, written by Jim Ratte, Scott Lynch, and Bill McIntosh, 2006, which summarizes the most recent research on the volcanic history of the Mogollon Range and Gila Wilderness.

- Mogollon Caldera and Bursum Caldera: Gila Nature Blog entry for March 2011, which gives an overview of the geologic history and evolution of the Super Volcanoes of the Gila Wilderness.

- Late Eocene or Early Oligocene Epochs of the Tertiary Period: This link will enable the reader to download the latest Geologic Time Scale produced by the Geological Society of America. This chart synthesizes and correlates the latest in absolute geologic dating (by radioactive decay methods) with the various Periods and Epochs of the geologic stratigraphic record.