TRACING ANCIENT TRAILS IN SOUTHWEST NEW MEXICO

by Frederic Remington, 1861-1909

The year was 1539 and the young Spanish Conquistador Francisco Vasquez de Coronado had just been installed as the new Governor of the Kingdom of Nueva Galicia, a province of New Spain located in northwest Mexico and comprising the present-day Mexican states of Jalisco, Sinaloa, and Nayarit. It was in September of that year when the Franciscan priest Friar Marcos de Nisa returned from an expedition into what is now northern New Mexico, confirming to Coronado the existence of a land of great wealth far to the north, the rumored Seven Cities of Gold, in a region known as Cibola. The rumor of golden cities was easily believed since only 20 years had passed since Hernan Cortes’s victorious conquest of the Aztec Empire in Mexico, and less than 10 years since Francisco Pizarro had conquered the rich Inca Empire in Peru, both of which had provided the Spanish Conquistadors with vast treasures of gold, silver, and precious stones.

In late February 1540, under commission from the first Viceroy of New Spain, Antonio de Mendoza, Coronado set forth from Compostela, Nayarit, as the leader of a major expedition to find and conquer the wealthy cities of Cibola. Documents written at the time report a very large expedition, which by one account consisted of some 250 horsemen, 70 Spanish foot soldiers, 300 native Mexican allies; plus over a 1,000 Indian servants, 4 Franciscan monks, (including Friar Marcos de Nisa as guide), and several slaves. In addition to the human contingent, it is thought that thousands of domestic animals were taken for transportation and food, including many hundreds of extra horses, pack mules, oxen, cows, sheep, and swine. The Expedition was divided into two groups: an advance party, under the leadership of General Coronado, of some 200 able-bodied men and servants who were able to move quickly and scout out the trail ahead, and the much-larger following party that traveled more slowly herding the support animals. By the time the advance party crossed the border into Arizona, the following support group was about three months behind the advance party.

The Coronado Expedition was to last three long years. Upon reaching and conquering by force the pueblo of Hawikuh in the Zuni Indian territory of Cibola (which Friar Marcos had seen only from a distance on his previous expedition), it was soon realized that Friar Marco’s exciting stories concerning the great wealth and treasures of the golden cities of Cibola were completely false. Indeed, as expedition foray after foray into the surrounding region returned empty-handed, it was obvious that the stories were no more than the wishful fabrications of the Friar’s imagination, based on nothing more than sunlight reflecting off the distant adobe pueblo walls of the Zuni Indians. Accordingly, Friar Marcos was sent home in disgrace.

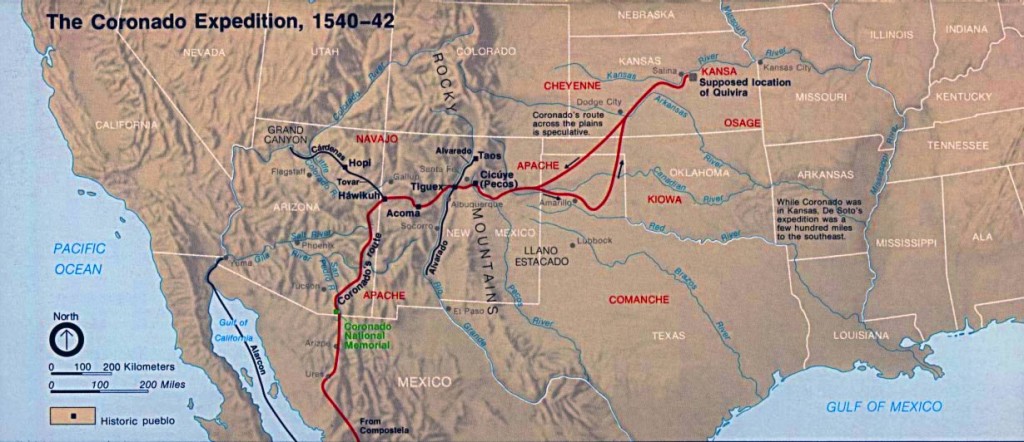

Not willing to give up, Coronado continued to explore areas to the west and east of Cibola over the next two years. The expedition made many new discoveries, including the Colorado River and the Grand Canyon to the west, and eventually journeyed east through vast areas of what is now northern New Mexico, northern Texas, the Oklahoma Panhandle, and south and central Kansas, in search of the rumored wealthy civilization of Quivira, that Indians assured him existed in that area (see map above—click on map for larger image). But it was not to be. There were no gold or other riches to be had in Quivira either.

Exhausted and dispirited, Coronado returned to Mexico in 1542. He remained governor of New Galicia for two more years, before the costs of the failed expedition forced him into bankruptcy since he had invested most of his and his wife’s wealth in the financing of the expedition. To complete his loss of prestige and honor he was ultimately accused of war crimes against the Pueblo people. He died in Mexico City of an infectious disease on July 21, 1554.

TRACING CORONADO’S TRAIL THROUGH ARIZONA AND NEW MEXICO

Until recently, traditional scholarly thought, such as that of Herbert E. Bolton, has been that Coronado, after crossing the border into Arizona and resting for several days at an abandoned pueblo site called Chichilticale in Coronado’s journals, was led north by native guides along a trail (see map above) just west of the Arizona–New Mexican border for a couple of hundred miles before turning east into New Mexico to arrive at the Zuni pueblo of Hawikuh, in the land of Cibola. In recent years, however, extensive field research in southeastern Arizona and western New Mexico by two independent investigators (S.M. Wells and N. Brasher) has presented substantial evidence in support of an alternative to the Arizona route that suggests that the most likely route north was in New Mexico, a few miles east of the Arizona State Line.

Based on a 10-year period of personal investigation studying ancient pueblo indian sites, Wells has mapped a number of ancient Indian trails in Southwest New Mexico which he believes served as important travel and trading routes between Northern and Southern population centers within the State. In time, Wells came to conclude that Coronado, using native Indian guides, most likely followed some of these same trails in his expedition north from Mexico to the Zuni pueblo of Hawikuh, particularly along the segments of what he considered a primary north-south Indian trail used from prehistoric times. This was a trail that came up from the south in Mexico to follow a route north through New Mexico, passing near today’s town of Deming, following the Arroyo San Vincente and Mangas Creek drainages south of Silver City, crossing the Gila River in the Gila and Cliff areas, and then continuing on north through today’s communities of Glenwood and Reserve. Much of this ancient trail followed the same route that one now travels today along US Highway 180 between Gila and Reserve, NM.

Wells’s map proposes that this primary Indian trail extending to the north had a significant junction point a few miles west of today’s junction of US Highway 180 and NM State Road 78, near the present day community of Mule Creek. Here the primary route was joined by another trail that came up from the southwest through what is now the community of Mule Creek. Wells’s investigations suggested that the trail coming up from the southwest closely followed a route now traversed by Brushy Mountain Road in Grant County, through the Apache Creek and Pine Cienega Creek drainages, before turning east to pass through Mule Creek and joining the primary north-south trail route now followed by US 180. About 14 miles south of Mule Creek, Wells proposes that this ancient Indian trail now followed by Brushy Mountain Road divided at a place now called Agate Spring. Here, one trail headed southeast to join the Gila River a few miles west of Red Rock, NM, near where Blue Creek joins the Gila from the north, and the other headed southwest to descend the Mogollon Rim escarpment from the Mule Creek Plateau near the Apache Box to cross the Gila River near Duncan, Arizona. (A great aerial view of the Mogollon Rim and Apache Box can be seen by entering Apache Box, NM, in Google Maps and toggling satellite view.)

Brasher has been conducting independent, ongoing research of Coronado’s route north from Mexico to Hawikuh in the Zuni Country since 2004. His research began with the objective of determining the exact location of the ancient abandoned pueblo site of Chichilticale, where, as described in a journal written by an expedition member, Coronado reportedly camped for a few days soon after leaving Mexico. Based on the details recorded in the journal regarding the Chichilticale campsite, Brasher considered its location an essential starting point in determining the continuing route north through Arizona and beyond. After several seasons of field work, Brasher and his team where successful in finding evidence which strongly suggests the location of Chichilticale as being the archaeological site now known as the Kuykendall Ruin, which is located on the southwest flank of the Chiricahua Mountains in Southeast Arizona. Here, Brasher’s team recovered numerous artifacts which further research indicated were most probably from the time of Coronado’s expedition. A detailed account of this initial research on Chichilticale, including many photos, can be found on Brasher’s extensive website.

Once the site of Chichilticale was conclusively determined, Brasher’s team focused their field research northward. Their efforts soon provided evidence that suggested Coronado, after leaving Chichilticale, had passed over the Chiricahua Mountains through Apache Pass, and had then crossed into New Mexico at Doubtful Canyon, a few miles north of where I-10 crosses into New Mexico from Arizona. From there, Brasher proposes that Coronado’s route headed north to cross the Gila River at, or just east of, where the major tributary of Blue Creek joins the Gila from the north. Interestingly, this crossing point correlates closely with the ancient Indian trail mapped by Wells, extending southeast from Agate Spring to the Gila River. From the Gila River northward, field research coupled with consideration of topographic and logistic restraints that would have faced Coronado’s large expedition, plus the finding of additional artifacts, have led Brasher and his team to outline a proposed route all the way north to Kawikuh. From Mule Creek north, both Wells’s and Brasher’s proposed routes are in agreement that Coronado’s route closely followed the present day route of US 180 between Mule Creek and Reserve.

TRACING CORONADO’S TRAIL IN MULE CREEK COUNTRY, GRANT COUNTY, NEW MEXICO

The Mule Creek Country of Southwest New Mexico offers all seekers of pristine Nature and Southwest history an exceptionally diverse and unique landscape to explore, hike, ponder, and enjoy. For purposes of discussion in this blog, the term “Mule Creek Country” describes a vast area in excess of 300 square miles, bounded on the west by the New Mexico–Arizona border, on the north by the San Francisco River, on the east by US 180, and a southern boundary line running from the community of Cliff on US 180 due west to the state line near the Apache Box Wilderness Study Area.

Topographically, the area is a rugged, highly-dissected, uplifted plateau of volcanic origin, having an average elevation of around 6,000 feet and mountain peaks up to 7,600 feet. Highest elevations of the plateau are in the western portions adjacent to the New Mexico-Arizona border, where the 1,500 to 2,000 foot escarpment of the Mogollon Rim rises abruptly from the Basin and Range desert lowlands of Arizona. From the crest of the Mogollon Rim the mountainous uplands extend eastward about eight miles through ponderosa, pinon, and alligator juniper forested terrain, before gradually dropping in elevation to the more open, gently rolling, juniper and pinon dotted grasslands that characterize the landscape in the vicinity of the community of Mule Creek and eastward to US 180. Except for a few private ranch land inholdings in valleys along major creek drainages that date from pioneer days, most of the mountainous western portion of the Mule Creek Plateau is part of the Gila National Forest. Most of the lower elevation grasslands in the eastern portion are large, privately-held ranch lands, which arguably is some the finest land for grazing in Southwest New Mexico.

The work of both Wells and Brasher suggests that after entering New Mexico, Coronado’s route north passed through Mule Creek Country. Wells’s research has suggested two ancient Indian trails that Coronado’s route may have taken north after crossing the Gila River. The first is a short but initially very steep trail that climbs up and over the Mogollon Rim to the Mule Creek Plateau in the vicinity of Apache Box, as shown on the Hobart Survey map of 1891, labeled the “Old Apache Trail”. The second is a longer trail several miles to the east that gradually ascends the Mule Creek Plateau by following the Blue Creek drainage northward from the Gila River. As described above, Wells suggests that these two trails merged at Agate Spring within the Apache Creek drainage and then continued northward along what is now Brushy Mountain Road. After leaving Agate Spring the trail would have followed Apache Creek upstream, soon passing by what in those days was probably a small pond or cienega (cienega is a Spanish word meaning “marshy place”) in the Apache Creek valley and then over a low topographic saddle to descend the Pine Cienega Creek drainage, passing by another marshy area at what is now Pine Cienega before turning east to follow Pine Cienega Creek downstream through what is now the community of Mule Creek. At this point the trail would have turned eastward to join with the ancient north-south trail now followed by US 180.

Brasher’s research proposes that Coronado’s route through Mule Creek Country crossed the Gila River just east of where Blue Creek joins it from the north and then followed the Blue Creek drainage north into the rolling, grass-covered eastern portion of Mule Creek County before turning east to join up with the US 180 route north.

A CHOICE OF TWO TRAILS

So if Coronado did pass through Mule Creek Country, which trail would he have taken: The Brushy Mountain High Country Trail or the Blue Creek Drainage Low Country Trail? At this point in time there is no definitive answer. Certainly much additional field research is needed. If and when it is done, the effort might result in conclusive evidence as to whether one of these two ancient Indian trails was indeed the route followed by Coronado over this segment of his journey.

While the two routes are separated by less than 10 miles in an east-west direction, for the first 12 to 15 miles each of them are very different in terms of types of terrain and vegetation. The Brushy Mountain High Country Trail would have offered a forested trail at an average elevation of 6,200 to 6,300 feet. At the time of the Expedition it would have offered a trail passing beneath towering, mature ponderosa pine, giant, centuries old alligator juniper, pinon pine, and gray oak, following Apache and Pine Cienega Creeks with shallow ponds or marshy areas along their courses. Large game animals and birds would have been abundant along this route, including elk, mule deer, and wild turkey.

The Blue Creek Low Country Trail, by contrast, would have presented a considerably longer trail through a much drier, mostly barren, creosote bush and mesquite and cactus studded rocky plateau and dry wash dissected country at an average elevation of 4,500-5,000 feet for the first 15 miles or so. Game animals and birds would probably have been very scarce over this stretch of trail. Continuing north, however, the trail would have gradually ascended into higher elevations of around 6,000 feet where more abundant grasslands and water sources typical of the eastern half of Mule Creek Country are found.

DID PREVAILING CLIMATE AND WEATHER FACTORS DETERMINE THE CHOICE?

To this writer it seems plausible that the Indian guides on the expedition would have been aware of both trails and what could be expected along each of these routes. Assuming that both routes were physically and logistically feasible for the expedition, it also seems likely that the weather and climatic conditions prevailing at the time of the expedition could have well been the deciding factor as to which route was taken.

Based on the accounts written by members of Coronado’s expedition, Brasher has put together calendars of both the Advance Party of the expedition’s journey north, which have Coronado passing through Mule Creek Country between July 4 and July 6, 1540, and the larger Following Party coming along some three months behind. In Southwestern New Mexico the Summer Monsoon Season rains historically start around the first week in July and last into the middle of September, following the two or three hottest and driest months of the year of April, May and June. Overall amount of rainfall received during the Summer Monsoons can vary considerably over the region, as well as on a local basis, depending on global weather and regional weather patterns, plus the local elevation (higher elevation receive greater rainfall). It is often the case in this area, particularly in La Nina years, that Spring rains are weak to nonexistent, and that the Monsoonal rains can be late arriving. As a result grasslands can be brown and dormant into August. Consequently, the status of the Spring rains and subsequent Monsoonal weather patterns in 1540 may have played a determining factor in choosing between the two trails.

There is no question that a trail ascending the Mogollon Rim by way of Apache Creek through the Apache Box would be extremely challenging if not impossible for the expedition because of the extreme topography of sheer, vertical canyon walls and cliffs, plus the chaos of fallen boulders choking the canyon. However, building upon Wells’s research, this writer’s analysis of satellite photography of the area shows that a little over a mile south of the Apache Box, at what is probably the location of Hobart’s Old Apache Trail, there is a smooth, constantly-sloping, and only slightly vegetated, broad-crested ridge running from the bottom to the top of the Mogollon Rim that displays no cliffs, rocky precipices or other insurmountable obstacles. Rising from the headwaters of Bitter Creek, which drains southwest to the Gila River about 14 miles away, this broad, ramp-like ridge rises about 900 feet vertically to a crest elevation of about 6,300 feet over a horizontal distance of just a little over one-half mile, at a remarkably constant slope of about 18-1/2°. While steep, it is not too steep and could be easily ascended by horse and humans in an hour or less. Having reached the summit of the Mogollon Rim on Hobart’s Old Apache Trail, it is then only about a three-mile trek across a slightly dissected upland grassland and juniper terrain to the Agate Spring trail junction in the Apache Creek drainage.

BRUSHY MOUNTAIN ROAD: A PASSAGE THROUGH ANTIQUITY

While there is presently no definitive research proving that Coronado’s route passed through Mule Creek Country following the Apache Creek/Pine Cienega drainages and present-day Brushy Mountain Road route, there is considerable evidence to suggest that this was an important, much used ancient trail that had been travelled by Native Americans for centuries. Numerous Indian sites are found throughout Mule Creek Country and along Brushy Mountain Road. Archaeology Southwest, a private nonprofit organization involved in preservation archaeology, has had an active program in the Mule Creek area for several years. A major research interest of the organization has centered on early cultural migration, change, and exchange routes throughout the Southern Southwest during the period between 1200 and 1540 A.D. An interesting part of this research has centered on the role that Mule Creek obsidian, as discussed in the August 2012 Casitas de Gila Nature Blog, has played as a major source material for projectile points and other stone tools for the Pit House and Pueblo Cultures throughout Southern Arizona and New Mexico. Mule Creek obsidian is a naturally occurring volcanic glass that occurs as abundant small nodules within the northwest quadrant of Mule Creek Country. Comparative spectrographic analyses of the trace element chemistry of obsidian stone tools found at archaeological sites as far west as Phoenix, some 200 miles away, have identified Mule Creek as the source area. Considering this, the question then emerges by what route did the Mule Creek obsidian make its way west to far off Southern Arizona or Southern New Mexico? Regardless of the ultimate final destination, in either case it is highly probable that the trail began with a journey south along the Brushy Mountain Road road route through Pine Cienega and Apache Creek to where the trail junctions at Agate Spring.

Historians and anthropologists both share disagreement as to when the nomadic Apache Indians first came into Southern New Mexico and Arizona. Some researchers place their arrival in the late 1500s, while others have them present there in the 1400s. Were they present when Coronado passed through? Possibly, but again, there are no definitive answers here either, for, as the Mexican and American Soldiers of the late 1800s came to know all to well, if the Apache didn’t want to be seen or found, they weren’t. In any case, it is highly probable that the Brushy Mountain Road route was well known and used by Native American people right up until the end of the Apache Wars and Geronimo’s surrender in 1886. It seems highly likely that the nomadic Apaches had used it extensively for at least 200 or 300 years, if not longer. That the Apaches used the Brushy Mounain Road route in more recent times is fairly certain as the war records and geographic place names still attest: Hobart’s 1891 map showing the Old Apache Trail, the Apache Box canyon, Apache Creek, and the side canyon off Apache Creek known as Geronimo Draw.

Without question, the route now followed by Brushy Mountain Road through Mule Creek Country is truly a Passage Through Antiquity, and for the visitor to the area it is a journey easily undertaken. Brushy Mountain Road begins at its signposted junction with NM State Road 78 in the center of “downtown” Mule Creek at the US Post Office at an elevation of 5,240 feet. For the next 15.5 miles the road runs through the heart of Mule Creek Country, mostly through the Gila National Forest, before ending at a locked gate where the road enters private land. The road is a well-kept, county-maintained gravel road that offers excellent hiking access into vast areas of rugged mountainous terrain within the very heart of the Mule Creek Plateau Country. The road is readily traveled by all types of vehicles, requiring neither high clearance nor four-wheel drive. About 12 miles south of Mule Creek, the Radar Station Road, a well-maintained road for all types of vehicles, goes off from Brushy Mountain Road to the north at a topographic saddle separating the northward flowing Pine Cienega Creek drainage from the southward flowing Apache Creek drainage. Radar Station Road offers an interesting drive up to the top of Brushy mountain at 7,600 feet, where spectacular views of Mule Creek Country and the far distant beyond greet the eye and camera in all directions.

Here at Casitas de Gila Guesthouses, we are quite familiar with several of the many special places to see, hike, photograph, and explore along this fascinating route through Mule Creek Country, having enjoyed many visits to the area ourselves. For Casita guests wishing to take a self-guided motor tour or off-road hike in this unique area, we have a written guide and maps that we can provide.