A THANKSGIVING HOLIDAY HIKE UP LITTLE DRY CREEK IN THE MOGOLLON MOUNTAINS OF THE GILA NATIONAL FOREST IN SOUTHWEST NEW MEXICO

Finding Nature’s Treasure Where Early Miners and Prospectors Toiled

A HIKE FOR THE OVERINDULGENT

The day after Thanksgiving dawned bright, crisp, and clear, absolutely perfect for walking off those over indulgences of the previous day’s feasting. It was to be a group hike, a mixture of three long-time, returning guests to Casitas de Gila Guesthouses, a couple of our good neighbor-friends and their dog Red, both of the Casita’s hosts, and our dogs Chloe and Bower.

Our destination of choice for the day was the Little Dry Creek Trail, Gila National Forest Trail 180, in the magnificent Mogollon Mountains of Catron County. The drive north along U.S. 180 was once more a visual feast but now of a totally different palate, with October’s golden leaves of the Mogollon High Country having been replaced a few days earlier by a heavy coating of snow, glistening brilliantly in the early-morning sun. Arriving at the trail head, it was not at all surprising to find that there were no other vehicles there. Nor would we encounter another soul on the trail that day; a typical experience and one of the most wonderful aspects of hiking in the Gila.

The Little Dry Creek Trail offers spectacular access into the heart of the Gila Wilderness. From the trail head on Little Dry Creek, at an elevation of 6,300 feet, the trail extends some 11.5 miles to terminate at Apache Cabin, at a lofty 10,200 feet in elevation, where it junctions with the Holt–Apache Trail, FT 181, coming in from the west. Our goal for the day was, of course, much more modest: a leisurely hike of two miles to the Gila Wilderness boundary, and if time permitted, possibly a little further to explore some of the old ruins and workings of the mining activity that thrived here in the Wilcox Mining District during the glory days of mining and prospecting that took place throughout Catron and Grant Counties during the past century.

THE WILCOX MINING DISTRICT OF THE MOGOLLON MOUNTAINS

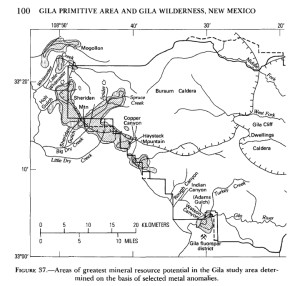

Between 1968 and 1971 an extensive and comprehensive mineral survey (Ref. 1) of the entire Gila Wilderness and adjacent Gila Primitive areas, was conducted by the U.S. Geological Survey and the the U.S. Bureau of Mines. The study, published by the U.S. Geological Survey in 1979 as USGS Bulletin 1451, delineated several areas in which anomalous concentrations of metals including beryllium, mercury, bismuth, antimony, arsenic, gold, silver tellurium, copper, molybdenum, lead, zinc, and manganese occur. The study concluded that the portion of the Gila Wilderness and adjacent primitive areas having the greatest mineral potential was within an area known as the Wilcox Mining District.

The Wilcox Mining District comprises an area some 15 miles long and a few miles wide that straddles the Gila Wilderness boundary that extends south and southwest along the front of the Mogollon Mountains between the towns of Glenwood and Gila. This area has been the focus of extensive prospecting and mining activity since 1879 when gold was discovered on Little Dry Creek. During the 1880s additional discoveries of gold were made within the district and in 1889 John Lambert and Dan Lannon discovered tellurium along with gold on a ridge about one mile east of Little Dry Creek near the top of Lone Pine Hill. Over the next 100 years approximately 1,500 claims were made within the district, including 16 patented claims and 2 patented mill sites. Quite a few of these claims were along Little Dry Creek, with the most intense activity concentrated near the present Gila Wilderness boundary.

During the many decades following the initial discoveries, countless prospectors and miners flocked into the rugged Mogollon High Country along Little Dry Creek and the rest of the Wilcox District area, setting off a gold and silver fever-fueled frenzy in which an incalculable amount of blood, sweat, and tears were expended. It is probably not much of an exaggeration to say that by the end of this hundred-year interval there was hardly a stone left unturned from the deepest canyons to the highest rocky peaks during their relentless search for the precious gold, silver and other metals.

Today, remnants of these perpetual pursuits can be encountered almost anywhere and when least expected while hiking the Forest trails within the District. Sometimes the evidence will be nothing more than an anomalous piece of rusted pipe or corrugated metal roofing poking through the leaves where an old cabin once stood. In other places the evidence is much more obvious, such as an abandoned piece of mining equipment near a grown-over prospecting trench, horizontal adit or shaft. And, oh what stories these remnants could tell regarding the many grubstakes won, lost, or squandered, only to be pursued again and again until the lack of funds, hope, or failing health brought these endless quests to their final demise!

Unlike some of the other mining districts in the Mogollon or Piños Altos Ranges or the Burro Mountains, there are no great strike-it-rich legends or success stories associated with the Wilcox Mining District. At least, that is, none that survive today. Known recorded production for the District is reported as consisted of only 10,912 tons of fluorite, 1.23 oz. of gold, 19 oz. silver, 50 tons of copper ore, 5 tons of copper-silver ore, 1.5 tons of copper-lead-zinc ore, and 5 tons of tellurium ore. What was really extracted and never reported, of course, will never be known. Prospectors and small-time mining operators are traditionally secretive by nature and not prone to keeping written records.

What is known, following the extensive sampling and chemical analyses made on materials collected at numerous known sites and workings within the district as part of the 1979 U.S. Geological report, is that the concentration of gold, silver, and other metals within the Wilcox Mining District is generally quite low, except for very thin veins and fracture fillings, typically only a few inches thick, which occasionally show promising concentrations.

Perusing the overall rather-uninspiring concentrations of heavy metals reported from the sample analyses of the 1979 USGS report, one can only wonder what kept these legions of prospectors and miners enthusiastically pursuing their elusive dreams of riches for all those years. Was it a case of simply blind hope, or perhaps the just-frequent-enough return of a marginally-rich-enough assay that kept them going? Or, perhaps, was it a more psychological attitude that prevailed in which the strike-it-rich stories constantly coming out of the very rich mineral discoveries and mines in the surrounding areas of Piños Altos, Silver City, and the Burro Mountains that goaded them into believing that surely those same riches lay just another few feet deeper in their own claims on Little Dry Creek. Or, which seems probably likely in some cases, did they really find small pockets of valuable concentrations and just kept quiet about it!

FINDING NATURE’S TREASURE ON LITTLE DRY CREEK

We’ll probably never know whether those seekers of treasure in decades past found what they were looking for. But at the end of the day on November 29, 2013, all of those participating in the Hike of the Indulgent agreed that they had found a superfluous abundance of Nature’s treasure on our little hike up Little Dry Creek.

Starting from the trail head parking area, which is accessible for all types of vehicles, the Little Dry Creek Trail follows an unmaintained, old mine road for a half mile or so before becoming a well-defined foot and horse trail that closely parallels and at widely-spaced intervals crosses Little Dry Creek as it heads up the canyon. While burned areas resulting from the Whitewater-Baldy fire of 2012 could be seen in the surrounding mountains as we worked our way up the trail, fire damage along the trail within the canyon was found to be minimal with almost all of the old growth ponderosa, fir, and spruce surviving with only scorched bark to show where ground fire had passed through. Studying the large slabs of bark on these massive giants of conifers that range up to three feet in diameter, it was obvious that many of them had experienced fire before.

The first mile or so of the trail was found to be in relatively good shape and easily followed, and the various creek crossings easily navigated by stepping across the many boulders that fill the crystal clear, shallow creek. Progressing further upstream into the second mile of our journey, in places the trail became a little more difficult to follow, particularly where the canyon bottom floodplain broadened and steep slopes of the adjacent canyon walls force the trail to the opposite side of the creek. At these places no trace of the trail existed across the floodplain due to the deposition of a two to four foot-thick layer of gravel and boulders that had been carried down the canyon late this past summer by major runoff following a 10-hour period of continuous stationary thunderstorm activity over the highest peaks in the southwest corner of the Mogollon Range on September 15, 2013. Crossing these boulder-strewn floodplain deposits was slow but not very difficult, and since the trail stays along the canyon bottom throughout this stretch of the trail, in most cases it was easy to predict where the trail would pick up on the opposite side above the floodplain.

About 1.25 miles into the hike, a well-constructed stone wall was encountered standing in mute testimony to one of the early miner’s cabins that once existed here on the east bank above the creek. From this point on, more remnants of former mining activity were encountered, each prompting their own set of questions, intrigue, and challenge to our curious minds as we pushed ever further up the canyon.

By 1:30 PM our GPS indicated that we were within two-tenths of a mile of the Gila Wilderness Boundary, our first goal for the day. However, with the canyon walls now closing in and towering increasingly high above, the trail was already in deep shadow and the first cold drafts of air of were beginning to flow down the canyon. In addition, there began to be grumblings of “when are we going to eat” and “I’m hungry” coming from the lesser indulgent of yesterday’s feasting. As the grumblings began to spread through the group and increase in frequency and intensity, it was with no little relief that as we rounded a bend in the canyon the perfect lunch spot appeared just 300 feet ahead … And it was still bathed in the afternoon Sun!

Settling ourselves down amongst the huge, flat-topped boulders that lined the creek, a great lunch was enjoyed by all, which we finished just as the Sun sank behind the western canyon rim 1,200 feet above. Donning our packs once more, some of our group scattered to explore our lunch spot before heading back. Within a few minutes they soon discovered that we were not the only ones to have found this a perfect spot. For just a hundred feet away from our picnic site were the scattered remnants of another miner’s cabin on one side of the creek and a shallow adit on the other. Oh, that rocks could talk, for what stories these stones could tell!

The retracing our of steps back down the canyon was a magical end to a perfect day, a journey through time as well as space. Increasingly, as the sun slid ever lower in the west, the trail along the canyon floor was transformed into a kaleidoscope pattern of light and dark as shafts of brilliant sunlight piercing through the trees alternated with chill-laced shadows cast from the cliffs far above.

Trudging along, it was noticed that in a similar way, one’s mood and thoughts seemed to fluctuate as well. While traversing the light, the immediacy of the surreal beauty of the sunlit pools and stones was overpowering, banishing all thought. Yet upon passing into the cool shadows, one’s thoughts would repeatedly return to pensive contemplation of those early miners and the spectrum of emotions that they must have experienced, as day after day they, too, trudged to and fro along this same canyon trail in their endless pursuit of the yellow and silver metal …

And then, an hour and a half later, it was over, as we emerged from the canyon and found ourselves at the trail head and once more back in the world of today. It had been a great day, and we returned home satisfied that we had indeed been successful in finding a full day’s worth of Nature’s Treasure on Little Dry Creek.

NOTE: The Little Dry Creek hike is an easy to moderate hike that for the first two miles follows a mostly easy-to-follow trail. The trail head is accessed from a maintained Forest road suitable for all types of vehicles. While there is water in the creek year around, it will require purification because of the presence of the protozoan parasite Giardia. Ample water, sunscreen, long sleeves and pants, and a wide-brimmed hat should be considered essential. The trail for the first two miles is generally accessible all year. Beyond that distance, snow may be encountered during December and January. During the Summer Monsoon season hikers should remain aware of thunderstorms and possible flash flooding in the afternoon. As always, Casitas de Gila will provide to our guests up-to-date weather and likely trail conditions, directions, and maps for any of the hikes in the area.

REFERENCES:

1. James C. Ratte, David L Gaskill, Gordon P.L. Eaton, Donald L. Peterson, Ronald B. Stotelmeyer and Henry C. Meeves, 1979, Mineral Resources of the Gila Primitive Area and Gila Wilderness, New Mexico, U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1451