LARGEST FOREST FIRE IN NEW MEXICO’S RECORDED HISTORY

It was early on the afternoon of May 16, 2012 while taking the trash from Casitas de Gila Guesthouses to the Gila transfer station, that one first noticed the fire about 25 miles away to the northwest: two small columns of smoke drifting lazily upward on the southern flank of the Mogollon Mountains. At that time the smoke seemed confined to two small areas, possibly the result of a controlled burn by the Forest Service. If not, one thought, then surely the Forest Service was aware of them since their presence and location could be readily seen from the Glenwood District Ranger Station. And surely, because of their apparent small size, they would be put out soon, and easily too. But, on both counts, it was not to be.

The Whitewater-Baldy Complex Fire began with a single lightning strike, first detected on May 9, 2012, as a small quarter-acre burn isolated on steep, grassy slopes on the side of Mogollon Baldy, a 10,770-foot mountain at the western end of the Gila Wilderness. Soon named the Baldy Fire by the Forest Service, the fire was not considered serious initially because of low amounts of fuel and some residual snow in the area where it was burning. Because of this assessment, the Forest Service placed the fire in monitoring status.

Then, about a week later, a second fire, named the Whitewater Fire and also the result of a lightning strike, was detected on May 16, high up in the headwaters of Whitewater Creek on the western slopes of Whitewater Baldy Mountain, the highest peak in the Mogollon Range at 10,895 feet. By May 23, the two fires had merged as a result of three days of winds over 40 miles an hour, and had turned into a raging monster of an inferno, rapidly consuming vast stands of old growth spruce and fir across the highest portions of the Mogollon Range. The Whitewater-Baldy Complex Fire was now a mega-fire, the size and intensity of which had not been seen within the Gila Wilderness in recorded history. The Whitewater Baldy Complex Fire was to burn for another two months. By the time containment of the fire was officially declared on July 17 and controlled status declared on July 31, the fire had burned over 297,000 acres, at an estimated cost of $100 million, making it the largest and most expensive fire in the history of New Mexico.

The progression, suppression, and aftermath mitigation efforts of the Whitewater-Baldy Complex Fire are well documented and make for interesting reading. The five summary documents listed in the References at the end of this blog give a good overview of the fire from several perspectives, plus a current statement of fire fighting protocol of the U.S. Forest Service.

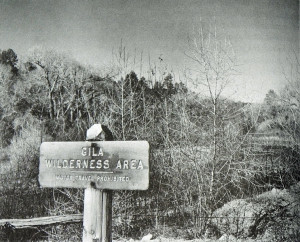

Almost immediately after the start of the Whitewater and Baldy fires, portions of the Gila Wilderness and surrounding National Forest were closed for safety reasons. Gradually, as the fire grew in size and magnitude, more and more areas had to be closed until virtually the entire western half of the Gila Wilderness and surrounding Forest west of the Gila River were closed to public access. This closure continued until August 9, 2013, when all areas and trails were reopened for public recreation and hunting.

THE NATURAL CYCLE OF WILDFIRE IN FORESTS

Forest fires caused by lightning are but one element of a vast, complex, eternally evolving, interconnected web of Cycles of Natural Change that exist within every forest. Wildfires in forests are not new; they have been part of Nature since the first forests began to cover the land in the Late Devonian Period 385 millions years ago.

Considered from Nature’s perspective, forest fires are neither good nor bad; they are simply a Natural Process of Cyclical Change. When viewed from the Human perspective, however, few people appreciate such a philosophical position. No, for most people forest fires are typically considered either good or bad depending upon one’s personal values. Neutral or indifferent positions are rare, especially when it’s a fire coming to a forest near (or dear) to you. Yet the fact remains … inhuman as it is to say it … Nature Doesn’t Care. Only humans care. Unfortunately (or fortunately—your choice), humans care about, or value, different things, values that are often diametrically opposed and mostly irreconcilable. And there’s the rub when you start talking about wildfire in forests. Game hunters or ranchers, for example, typically view forest fires as beneficial in the long run because more grass-covered open land equals more game and more grazing! On the other hand, to the advocate of the endangered Spotted Owl or the devotee of majestic stands of old growth, pristine spruce and fir, or the owner of that little cabin retreat in the pines in a private inholding surrounded by National Forest, wildfire in the forest is a threat and should be stopped. And so it goes—different values, different perspectives. Our National Forests – Lands of Many Uses, Lands of Many Values.

HISTORIC AMERICAN RESPONSE TO WILDFIRE IN FORESTS

The history of response to wildfire in the forest in the United States, especially in the American West where periods of extended drought are more common, has varied throughout our history. Prior to 1900, most people saw the American Forest as something to be used; lumber, minerals, potential farm or ranch land, source of food, etc., all God given and free for the taking. And from this perspective, fires in the forest were mostly considered not good, something to be feared and fought, and to be put out wherever possible. Unless, of course, one wanted to start one’s own fire and use it as a means to clear land for other uses. Concepts such as conservation and preservation were given little thought in the Western Frontier. By the early 1900s some scientists and naturalists, such as Aldo Leopold, were beginning to speak out about these concepts, as greater insight and understanding emerged regarding the role that various natural cycles, such as wildfire, played in forest ecology.

Then came the Great Fire of 1910, also known as the Big Burn or the Big Blowup. As inconceivably large as the Whitewater-Baldy Complex Fire at 300,000 acres seems to most people today, by Big Burn standards it would be considered perhaps nothing more than a good-sized brushfire. When the Big Burn Fire was finally extinguished by Mother Nature in the form of a cold front that brought major rain and snow, over 3 million acres or 4,700 square miles (roughly the area of Connecticut) had been charred over Northeast Washington, the Panhandle of Idaho, and Western Montana in

With the aftermath of the Great Fire of 1910 came a National Policy for the newly established, five-year-old U.S. Forest Service: a non-negotiable policy of complete fire suppression. This far-reaching policy was to last until the 1960s when discussions began to take place at the National level regarding the recognition that fire in the forest was a natural process and that forests should be managed as ecological systems, a concept embracing the conviction that total suppression was not always the best solution. As a result of these discussions, and with the passage of the Wilderness Act in 1964, naturally-caused fires were permitted to burn within the newly-established Wilderness Areas. In 1968, the National Park Service policy regarding wildfire was likewise changed, recognizing fire as a natural process. As a result, wildland fires were permitted to burn within our National Parks as long as the fires achieved management objectives. Finally, in 1974, the U.S. Forest Service abandoned its 64-year policy of complete fire suppression (which had been formalized in 1935 by the adoption of the so-called 10:00 AM Policy, a hard-line, no excuse policy that mandated that all fires within National Forests would be suppressed by 10:00 AM the day after they were detected), and embraced a more ecologically-based policy of prescribed fire management involving both suppression, allowing certain fires to burn, and the setting of prescribed controlled burns. Since that time, the protocol for prescribed fire management has evolved as experience was gained from major fires that occurred within fire suppression or exclusion zones, wildfire escapes from controlled burns, and the extensive monitoring of naturally-occurring wildfires throughout the West. As a result of this experience, although today’s management programs will vary somewhat from agency to agency, the first priority and prime directive for all federal wildland fire programs is that of firefighter and public safety.

FALL 2013: A RETURN TO THE TRAILS OF THE GILA NATIONAL FOREST AND WILDERNESS

As of August 9, 2013, all areas of the Gila Wilderness that were closed in 2012 because of the Whitewater-Baldy Complex Fire are once again open to the public. For the remainder of 2013, visitors to the Gila Wilderness and National Forest should be aware that some roads, trails and recreational areas are still being repaired or remain in poor condition as a result of the fire and subsequent damage from the 2012 and 2013 Monsoon rains.

The Monsoon Season for 2013, which began at the Casitas de Gila Guesthouses on July 1, is now over throughout the area, with the last rain received here on September 20. This year’s Monsoon Season was a long one, with most areas receiving substantial rainfall. Here at the Casitas total rainfall for the period was 11.4 inches, about twice the normal average. Higher elevations in the mountains and Wilderness areas, however, received greater amounts, with some areas, particularly in the western part of the Mogollon Mountains, reporting as much as 25 inches. While the Whitewater-Baldy Complex Fire covered a vast area of the Gila Wilderness, the most severely burned areas also occurred in the highest elevations in the western part of the Mogollon Mountains. Consequently, serious flooding occurred here in the latter part of the Monsoon Season, particularly in the Whitewater Creek, Silver Creek, Mineral Creek, and Gilita Creek drainages, leading to downstream damage in the communities of Alma, Mogollon, and Glenwood.

During the Fall Season from late September through December, hiking, birding, touring, camping, and other recreational pursuits are at their best in the Gila National Forest and Gila Wilderness. Typically the skies are clear, the air cool and crisp, and precipitation nil, with rivers and creeks running at normal levels and clear. This statement, of course, was significantly compromised last year in the aftermath of the 2012 Whitewater-Baldy Complex Fire, with major trail, road, and area closures; rivers and creeks running black from colloidal ash and silt runoff; and charred, barren landscapes in the high country. This year, just one year later, however, visitors to the area will once again be able to experience the solitude and magnificence of the Gila Country and all that it has to offer.

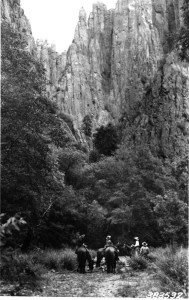

Most popular day trips and hikes along roads and trails within the lower elevations and periphery of the Gila National Forest and Gila Wilderness show little or no sign of burning from the Whitewater-Baldy Complex Fire since the most severe burning was confined to the highest elevations in the interior of the Wilderness. Where such effects are encountered they tend to be isolated and small in area extent, the result of localized fire spotting from wind blown embers. Most lower elevation canyons and creeks show minimal effect, whereas adjacent ridge-tops may exhibit more extensive burning.

It is true that some favorite area trails in the high country are difficult to access and traverse, and will remain so for considerable time, as many of these areas were greatly changed by the fire. Yet if one does choose to travel these areas, one will be impressed to find a forest well into comeback mode, with much of last year’s barren landscape now showing an abundant growth of new grass, shrubs, and young trees. The Natural Cycle of Forest Regeneration and Succession has begun. And if one is able to focus on the present and what will eventually be again, without excessive obsessing on what once was, such a visit offers the potential for a rewarding experience of observation and insight as to how Nature never gives up, but instead adapts and perseveres within the never-ending Processes of Cyclical Change.

When planning a hike or visit within the Gila National Forest or Wilderness this Fall or Winter, it is strongly suggested that one contact the Gila National Forest District Ranger Station in Glenwood (575-539-2481) regarding road and trail conditions in specific areas, as maintenance and repairs following the Whitewater-Baldy Complex Fire will be ongoing during this time period. Visitors that have computer access will find the Google Earth program to be of great value in planning and previewing a hike or outing since new high-definition imagery of the Gila Wilderness was taken this year on February 22, 2013. By comparing this imagery with the newly revised map of the Gila National Forest that came out on September 13, 2013, one should be able to determine probable conditions on various trails and roads.

Here at Casitas de Gila we do our best to stay updated on existing conditions on various roads and trails and are always happy to provide information and maps for our guests. And, as always, we will be pleased to give full directions and information regarding any hikes discussed or pictured in this blog.

REFERENCES

These reports and documents present a good detailed summary and statistics of the beginning, progression, and aftermath of the Whitewater-Baldy Complex Fire.

- Wildfire Review Report of Whitewater-Baldy Complex and Little Bear Fires in New Mexico, May through June 2012 (.pdf file), William A. Derr, Legislative Fellow for Steve Pearce, Member of Congress, Second District, New Mexico.

- Narrative of Whitewater Baldy Complex Fire May, 23rd, 2012 to June 19th, 2012 (.pdf file), Observations and actions by Doug Bohykin, Socorro District Forester, NM EMNRD, Socorro District, New Mexico.

- Whitewater Fire, A Lasting Legacy (.pdf file), Alan Campbell.

- Whitewater-Baldy Complex, Burned Area Emergency Response (BAER) Team, Executive Summary, Glenwood, Reserve, Black Range, and Wilderness Ranger Districts Gila National Forest (.pdf file)

- 2013 U.S. National Forest Service Wildland Fire Response Protocol (.pdf file)