THAT TRANSFORMED CASITAS DE GILA GUESTHOUSES

INTO A WINTER WONDERLAND

WINTER CLIMATE IN THE SOUTHWEST:

CONTROLLING FACTORS, AVERAGES, AND EXCEPTIONS

The average Winter snowfall received at Casitas de Gila Guesthouses and Southwest New Mexico is a function of several factors, including:

- the large scale alternating weather pattern in the Pacific Ocean known as the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), which results in the periodic warming and cooling of sea surface temperatures across the Pacific within the tropics and subtropics, and the creation of the important climatic patterns commonly referred to as El Niño (warm) and La Niña (cool) episodes

- large-scale Jet Stream patterns over western North America

- prevailing local atmospheric pressure and temperature

- local elevation

Climatic Affects of El Niño and La Niña Winters on New Mexico

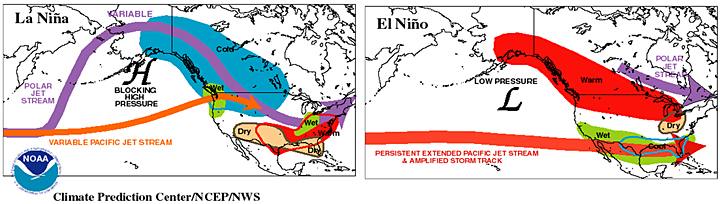

Historical records show that El Niño winters in the Southwest are marked by increased precipitation and warmer temperatures, and La Niña winters by decreased precipitation and colder temperatures. During El Niño years, moisture-laden Low Pressure systems coming in off the Pacific Ocean tend to follow a southern route, carried along by the west-to-east flow of a persistent Pacific Jet Stream across the Southwest and into southern New Mexico (see figure below.) During La Niña years, however, eastward-moving, moisture-laden Low Pressure systems coming in off the Pacific Ocean tend to take more northerly routes across the western U.S., carried along by the west-to-east variable flows of the Pacific and Polar Jet Streams, bringing dry, sunny High Pressure conditions to prevail over the Southwest and New Mexico.

Monitoring Oscillations of El Niño and La Niña by the Oceanic Niño Index

Sea surface temperatures fluctuate constantly in the Central Pacific along the equator, and when monitored and averaged over time demonstrate repeated oscillations between El Niño (warm) and La Niña (cold) episodes. The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) monitors these oscillations by averaging monthly measurements of surface sea water temperatures collected over an area that covers the central portion of the Pacific Ocean between 5°N and 5°S latitude and 120° to170° W longitude. These temperature fluctuations, when averaged over successive three-month intervals during the year (which NOAA refers to as “seasons”), yield temperature anomalies that NOAA calls the Oceanic Niño Index (ONI). ONI values generally lie within 3°C of the average temperature for any given area at any specific time of the year. Anomalies that deviate from the average temperature in excess of +0.5°C mark a shift towards a warm El Niño episode, whereas anomalies in excess of -0.5°C mark a shift towards a cold La Niña episode. Anomalies that are between ±0.5°C are called a Neutral Episode, or, as they are sometimes humorously referred to, a La Nada episode. By NOAA’s definition, an El Niño or La Niña Episode can only be so named when the average of three consecutive ONI three-month seasonal values exceed the ±0.5°C threshold.

The Oceanic Niño Index has been in a Neutral or La Nada episode since the March-April-May seasonal ONI of 2012, and current projections (.pdf file) as of January 19, 2015 are that of a 50-60% chance of weak El Niño conditions during February and March, with a ENSO Neutral episode thereafter.

PREVAILING CLIMATIC CONDITIONS THAT SET UP

THE GREAT SNOW OF JANUARY 2, 2015

Typically, winter snowfall at the Casitas for the past 16 years has consisted of two or three light snowfalls each year, with each amounting to two or three inches or less. Generally, these snowfalls occur in the following predicable pattern: As low pressure systems come in from the west, winds are out of the southeast bringing warm air up from Mexico, which causes the precipitation to start as rain. Then, as the low pressure system passes by heading east, the precipitation may turn to snow overnight as the winds shift to the north. Once the storm has passed by, the skies clear, and the brilliant New Mexico Sun returns, the snow melts off quickly, typically during the following day.

Casitas de Gila is situated at an elevation of 4,800 feet. Small differences of elevation on the order of just a few hundred feet can result in a change in precipitation falling as rain or snow. For example, it is not uncommon during a Winter precipitation event at the Casitas for the 5,500 foot summits of North and South peaks (they rise up directly east of the Casitas on the other side of Bear Creek) to be coated with snow, while the Casitas receive nothing but rain. As another example, Silver City, which lies at an elevation of 6,000 feet, gets at least twice as much snow as the Casitas during the Winter.

The Great Snow of January 2, 2015, however, did not follow this usual pattern at all, but instead resulted from an unusual set of climatic factors: 1) A La Nada to very weak El Niño pattern had prevailed during the last weeks of 2014, and 2) Jet Stream patterns in the western U.S. were complex, not resembling either of the simple patterns shown in Figure 1. Instead, the Jet Stream patterns were repeatedly developing into very unusual, complex loops that came south down along the west coast of the U.S. from Canada, bringing masses of cold arctic air to the Southwest before angling northeast to bring rain to East Coast. By January 1, the Jet Stream had split, developing a pattern more like the El Niño pattern shown in Figure 1, with a Northern Polar Jet Stream and a southern Pacific Jet Stream which was now bringing up warm, moist air from Baja California. With cold air still lingering in the upper atmosphere from the previous loop pattern and the subsequent influx of moist air from the south, the stage was now set for the Great Snow of January 2, 2015. On that day it snowed all day, dropping a total of between 7 and 8 inches and turning Casitas de Gila into a Winter Wonderland. While old timers of the Gila area said they could remember greater snowfalls in the past, younger locals could not, and for certain it was the greatest snowfall the Casitas had experienced in 16 years of operation. Even so, by noon the following day with the combined efforts of El Sol and the trusty Casita tractor, all roads were passable, permitting both departing guests to leave and arriving guests to arrive.

A WINTER WONDERLAND AT CASITAS DE GILA GUESTHOUSES

The snowfall began in the early morning hours of January 2 with a couple inches of light dry snow on the ground by 8 AM. Despite a few brief periods when it appeared that the snow would soon stop, in never did until late in the afternoon when, as darkness approached, the skies finally began to clear.

With dawn, the habitual early morning walk past the Casitas and down along Bear Creek to the horse corral revealed a true Winter Wonderland. On the flat to the west of the Casitas, Mule Deer (Odocoileus hemionus) and Desert Cottontail Rabbit (Sylvilagus auduboni) tracks criss-crossed the snow-covered road. Here and there Bobcat tracks followed the rabbit tracks, although evidence of an actual encounter was not found. Our two English Springer Spaniels were very excited by it all, sniffing, frolicking, rolling, and chasing one another all the way to the corral and back. The One-seed Juniper (Juniperus monosperma), Soaptree Yucca (Yucca elata), and Cane Cholla Cactus (Cylindropuntia spinosior) were all resplendent in their new, thick blanket of white, the juniper branches sagging under the unaccustomed weight. For most of the guests, it was a great day for hunkering down inside their Casita, enjoying the cheer of hot chocolate and a good book by their kiva fireplace; but by the afternoon the incredible natural beauty steadily enveloping the Casitas was too much to ignore, prompting several photographic pilgrimages down to the Creek.

With the low pressure system now past and heading east, the night of January 2 came on cold and clear. Slowly, the near-full moon rose above North and South peaks, casting the snowscape in the mystic bluish light and dark shadow that can only be experienced following a fresh heavy snowfall. Magical!

With the next morning’s light, the dogs found the trip to the Creek even more exciting, the deeper snow coming up to their bellies. It seemed, however, that most of Nature’s furry friends were still sleeping in, as only a few deer and rabbit tracks were found crossing the road by the Creek. As expected, when dawn broke and the first rays of El Sol emerged from behind North and South peaks, the landscape surrounding the Casitas was immersed in endless waves of brilliant light. A trip along the Creek was a must to document this rare natural spectacle before it melted away.

Traveling upstream from the Casitas’s southern boundary, it was hard to progress more than a few yards before yet another photo opportunity would present itself. Bear Creek gurgled sharply in the morning silence. The maze of cottonwoods and willows lining the creek glistened yellow-white in the morning light, with every snow-frosted branch and twig etched in sharp contrast against the cerulean sky, while deep shadows of cobalt blue criss-crossed at their feet. Here and there the maze of yellow-white and blue would suddenly be broken, as a lone sycamore would burst into view, its rusty-red leaves ablaze in the light.

Along the margins of the Creek, narrow bands of wet, reddish-brown sand and gravel marked the edge of the warm, upwelling spring-fed waters. For most of its course past the Casitas, the waters of Bear Creek rarely freeze in the Winter because of the vertical circulation and mixing of warmer waters rising and colder waters sinking within the thick deposits of loose sand and gravel sediment that make up the stream bed of Bear Creek. Through this upwelling circulation the waters are warm enough in places that occasional patches of bright Springtime-green Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) and Pale Duckweed were encountered, flourishing in defiant counterpoint to the surrounding Mid-Winter snowscape.

Continuing further up the creek, immersed in the cold shadows of the towering cliffs above, one soon came to a higher-energy, rocky portion of the creek where, during the Great Bear Creek Flash Flood of last Fall, concentrations of large pebbles, cobbles, and boulders were deposited in thick gravel bar deposits along the margins of the Creek, while the finer sediments were swept away. Here in this cliff-shadowed segment of the Creek, there were no signs of the warm, upwelling spring-fed waters just observed a short distance downstream. Instead, the stream bank remained frozen solid to the water’s edge, and where former gravel bars were once observed, the Creek margin was now transformed into a lumpy expanse of stoney-cored, oversized marshmallows glistening in the morning Sun.

Tracks of animals, some fresh, some old, were abundant in most places along the Creek – Mule Deer coming to drink and feed on the Watercress and Duckweed, Rocky Mountain Big Horn Sheep coming down off the cliffs to the water, the five-toed, telltale track of the elusive White-nosed Coatimundi (Nasua narica), small tracks of Mice (Family: Cricetidae) and larger tracks of the Gray Fox (Urocyon cineroargenteus) hunting the mice; but on this day, no sign of Mr. or Mrs. Mountain Lion (Puma concolor).

As the morning wore on and the snow began to fall from the trees, creating a little plop here and a little kerplop there, a variety of birds including the Wood Thrush, the Ruby-Crowned Kinglet, and the Black Phoebe were found feeding on insects near a large pool of water situated in the middle of the floodplain, a short distance east of the main Creek Channel. The pool, which has persisted at this particular location for several years now, is elongated in shape, measuring up to several feet across and a couple of hundred feet long, with water depths ranging from a few inches to up to a foot. Interestingly, the water level in the pool is elevated a foot or two above the level of the main channel of the Creek into which it drains.

Observations made over the years reveal that this pool is formed by confined subsurface creek waters that rise to the surface of the floodplain at this spot from an abandoned main creek channel that was buried with fine silt and mud when the creek changed its course during the Great Flood of 2005. Because the pool is fed by warm water rising to the surface of the floodplain, Watercress and Duckweed flourish on the pool’s surface year around, which seems to be a delicacy for the Mule Deer in the winter, judging by the abundance of tracks at the water’s edge. Peering into the water, small minnows could be seen cruising up and down the length of the pool continuously, only to instantly disappear and hide beneath the floating Watercress and Duckweed whenever danger was sensed in the shadows cast from above. A variety of small insects also abound here year around, in the water, along the margins of the pool, and incredibly and to the obvious delight of the Black Phoebe on this sunny warming day, even flying just above the surface of the water. Observing this smorgasbord of Nature’s bounty it was as if one had suddenly time-travelled from a Mid-winter Snowscape into Early Spring.

By noon the melting of the snow was in full display, with snow dropping noisily from the branches of the large oaks and junipers bordering the floodplain. Having just started the short hike back to the Casitas, a bird flew close overhead to land on the trunk of a tall juniper about 60 feet distant and instantly began pecking away. At that distance, it appeared to be a Ladder-Back Woodpecker and remained there fully engaged in its foraging for about a minute, quite long enough to permit several telephoto pictures. Looking at the photos back in the studio, it was quickly obvious that the bird was not a Ladder-back, but rather a new bird that had never been reported at the Casitas. It was a Red-naped Sapsucker! What a colorful and handsome bird they are. And, what a marvelous hike it had been!