CLIMATIC OSCILLATION CYCLE WITHIN THE BEAR CREEK NATURE PRESERVE

AT CASITAS DE GILA GUESTHOUSES

CLIMATIC AFFECTS OF EL NIÑO AND LA NIÑA WINTERS ON SOUTHERN NEW MEXICO

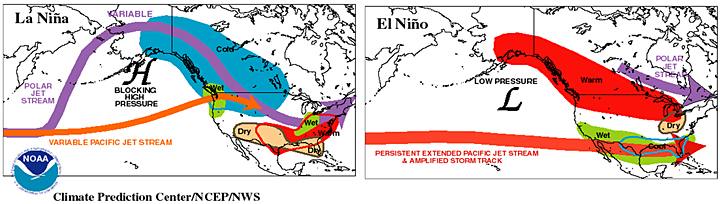

Historical records show that El Niño winters in the Southwest are marked by increased precipitation and warmer temperatures, while La Niña winters are marked by decreased precipitation and colder temperatures. During El Niño years, moisture-laden low pressure systems coming in off the Pacific Ocean tend to follow a southern route, carried along by the west-to-east flow of a persistent Pacific Jet Stream across the Southwest and into southern New Mexico (see Figure 1 below.) During La Niña years, however, eastward-moving, moisture-laden low pressure systems coming in off the Pacific Ocean tend to take more northerly routes across the western U.S., carried along by the west-to-east variable flows of the Pacific and Polar Jet Streams, bringing dry, sunny high pressure conditions to prevail over the Southwest and New Mexico.

MONITORING OSCILLATIONS OF EL NIÑO AND LA NIÑA BY THE OCEANIC NINO INDEX (ONI)

Sea surface temperatures fluctuate constantly in the Central Pacific along the equator, and when monitored and averaged over time demonstrate repeated oscillations between El Niño (warm) and La Niña (cold) episodes. The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) monitors these oscillations by averaging monthly measurements of surface sea water temperatures collected over an area that covers the central portion of the Pacific Ocean between 5°N and 5°S latitude and 120° to 170° W longitude. These temperature fluctuations, when averaged over successive three-month intervals during the year (which NOAA refers to as “seasons”), yield temperature anomalies that NOAA calls the Oceanic Niño Index (ONI). ONI values generally lie within 3°C of the average temperature for any given area at any specific time of the year. Anomalies that deviate from the average temperature in excess of +0.5°C mark a shift towards a warm El Niño episode, whereas anomalies in excess of -0.5°C mark a shift towards a cold La Niña episode. Anomalies that are between ±0.5°C are called a Neutral Episode, or, as they are sometimes humorously referred to, a La Nada episode. By NOAA’s definition, an El Niño or La Niña episode can only be so named when the average of three consecutive ONI three-month seasonal values exceed the ±0.5°C threshold.

CYCLES OF EL NIÑO AND LA NIÑA FOR NORTH AMERICA 1950 to 2015

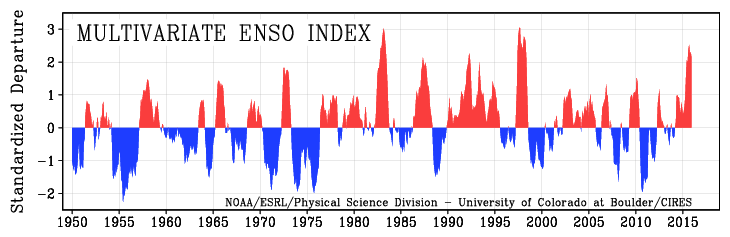

When plotted through time as shown in Figure 2 below, it is very clear that El Nino and La Nina episodes are predictably cyclic in nature, with an average duration between 3 and 4 years. Although these episodes do show variability in both duration and intensity, they are not unusual in any way, and are just another of Nature’s cycles that has a pronounced affect upon the natural environment and plant and animal populations in the American Southwest.

THE TRANSITION OF THE RECENT LA NADA EPISODE OF MARCH 2012 TO EARLY 2015 INTO THE VERY STRONG EL NIÑO OF 2015 – EARLY 2016

As can be seen in the Oceanic Niño Index, the American Southwest entered a Neutral or La Nada episode beginning around March of 2012. This La Nada episode continued throughout the rest of 2012, 2013, 2014, and into the first two three-month monitoring periods of 2015. However, beginning in the third three-month interval of February/March/April 2015, the ONI shows a weak El Nino episode gradually strengthening throughout the year to become a very strong El Nino episode by December 2015. Current projections (.pdf file) as of January 4, 2016, have the strong El Niño conditions continuing throughout the rest of the 2015-16 Winter, followed by a slow transition into an ENSO Neutral episode or La Nada situation by Late Spring or Early Summer.

PRECIPITATION DATA COLLECTED AT CASITAS DE GILA ILLUSTRATE THE TRANSITION OF A PERSISTENT LA NADA EPISODE TO A STRONG EL NIÑO EPISODE BETWEEN MARCH 2012 and DECEMBER 2015

Precipitation at Casitas de Gila has been monitored electronically on a daily basis for many years. Some of this data is presented in Tables 1 and 2 below. Examination of this precipitation data illustrates the transition of a persistent La Nada episode to a strong El Niño episode between March 2012 and December 2015.

As can be seen in Tables 1 and 2, there is a marked increase in precipitation from 2012 to 2015, on a yearly total basis and also when comparing Fall and Winter month totals. The NOAA projection for the Oceanic Niño Index (ONI) for the remainder of the 2015–16 Winter is to remain in an El Niño episode, returning to a Neutral or La Nada episode in Late Spring or Early Summer. If this projection holds true, the Fall and Winter total precipitation should exceed the 2014-15 total precipitation.

SOME OBSERVED POSSIBLE AFFECTS OF THE TRANSITION OF THE LA NADA EPISODE OF 2012 TO 2015 INTO THE STRONG EL NIÑO EPISODE OF 2015 UPON THE FLORA AND FAUNA OF THE BEAR CREEK NATURE PRESERVE AT CASITAS DE GILA

Casitas de Gila is situated on the western edge of Bear Creek Canyon about 80 feet above the Creek overlooking the 265 acres, 3/4 mile of Bear Creek, and 6 miles of trails that constitute the Bear Creek Nature Preserve.

During the time period from March 2012 and December 2015, various changes have been observed in the flora and fauna of the Bear Creek Nature Preserve at Casitas de Gila Guesthouses which may be in response to the transition from the La Nada episode to a very strong El Niño episode as documented in Tables 1 and 2. Some of these observations are presented below. In considering these observations, it must be stressed that they are the result of long-term, daily, on-site personal observations only, and not the conclusions of a rigorous scientific study. It is also important to remember the important principle that must always be kept in mind when dealing with any study of Nature, namely: that “Correlation does not necessarily equate to Causation”. With those caveats stated, the following possible affects of the transition of the La Nada episode of 2012 into the strong El Niño of 2015 are presented:

OBSERVED TRENDS IN FLORA AT THE BEAR CREEK NATURE PRESERVE 2012 to 2015

• During and in the months immediately following the very dry year of 2012 (total precipitation 6.86 inches), and cold Winter of 2012-13, flowering and seed production of trees, shrubs and grasses at the Casitas were much below normal. Numerous individual plants of several species, such as the Turpentine Bush (Ericameria laricifolia) and Engelmann Prickly Pear (Opuntia engelmannii), on the Casitas’ Self-Guided Nature Trail were observed to die. Spring flowers in particular were notably absent.

• As yearly and Fall/Winter precipitation steadily increased during the transition from La Nada to El Nino, flowering and seed production likewise increased, culminating in the Spring of 2015 when a profusion of flowers occurred over the Casita lands. So profuse and obvious was this prolific flowering of diverse species (some of which had not been seen in many years, and others, such as the Doubting Maricopa Lily (Calochortus ambiguus), had never been observed or recorded previously at the Casitas), that it became the subject of two Nature Blogs in March and April of 2015.

OBSERVED TRENDS IN FAUNA AT THE BEAR CREEK NATURE PRESERVE 2012 to 2015

• 2012 was a year of severe drought and a very difficult time for animals both at Casitas de Gila and at the adjacent Gila National Forest and Gila Wilderness. This was also the year of the Whitewater-Baldy Complex Fire which became the largest forest fire in New Mexico’s recorded history.The fire started on the west side of the Mogollon Mountains just within the Gila Wilderness about 25 miles northwest of Casitas de Gila on May 9, 2012, when two dry-lightening strikes touched off the drought-parched forest. The resulting conflagration was finally declared controlled on July 31, after burning some 297,000 acres of the 600,000 acres of the Gila Wilderness, at an estimated cost of $100 million dollars. This incredibly destructive fire was the subject of a Nature Blog in September 2013.

The combination of the Whitewater-Baldy fire and the ongoing drought of 2012 resulted in some expected and unexpected changes in animal populations and occurrences within the Bear Creek Nature Preserve.

• With the lack of Spring rains in 2012, stock tanks in the mountains adjacent the Bear Creek Nature Preserve dried up early and normal Spring grass and shrub vegetation in the uplands was deficient to completely lacking. Consequently, Bear Creek in front of the Casitas (which always has water in it year around) saw an increase in animals, both large and small, as it was the only source of water and food around. Some of the increase was probably also due to animals fleeing the Whitewater-Baldy Fire in the adjacent Gila Wilderness. Black Bear, Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep, and Mountain Lion (the only predator of the Bighorn Sheep) sightings at the Casitas and on Bear Creek were up. Adult Bighorn populations seemed normal; however, only two newborn lambs were observed during 2012 at any one time on the cliffs following lambing in Late Spring. In June a mother Black Bear brought her two cubs to Bear Creek for food and water, and for the first and only time in the 18 years history of the Casitas, garbage cans were raided by the bears.

• In 2013 and 2014, precipitation increased as the overall climate moved towards the El Niño episode. In the early morning hours of September 22, 2014, the largest flash flood ever recorded at Casitas de Gila in its 18-year history occurred when the remnants of a major hurricane in Baja California triggered a series of thunder storms traveling down the Bear Creek drainage from its headwaters in Pinos Altos, creating a flood crest of 12 feet above normal Creek level. The effect of this flood upon less-mobile animals, such as reptiles and amphibians, was undoubtedly devastating, as their observed populations were significantly less in succeeding months.

Most other animals were observed to prosper during 2013 and 2014. During this time the frequency and count of both Bighorn Sheep and Mule Deer sightings increased in 2013, with five Bighorn lambs observed in Late Spring. No Bighorn lambs were observed or recorded in 2014, however.

• In 2015, the El Niño episode arrived with the greatest total yearly rainfall in four years. It was a year of relative plenty in terms of both food and water for all animals, big and small. Bighorn sightings increased with up to 16 individuals observed at one time, 5 of which were lambs. Mule Deer sightings were also up in frequency and count number. Small animals such as Rabbit (both Cottontail and Jackrabbit), Gray Fox, and Field Mice appeared to be much more abundant than in previous years. By the end of the year the Gray Fox population obviously had boomed, based on the amount of scat observed around the Casitas. The chipmunk population, however, was noted as having greatly declined by the end of 2015. Mr. and Mrs. Fox? Most likely.

SUMMARY

When all of these various observations are considered together, it is clear that the climatic impact of the La Nada to El Niño transition upon plant and animal populations and the overall food chain during the cyclical transition from the 2012 drought to abundant precipitation in 2015 is definitely mirrored in the observed cycles of plant and animal population and reproduction variability. Some of these cyclical changes are obvious, others only suggested. What is certain, however, is that the overall ecology of the Bear Creek Nature Preserve provides a unique opportunity to observe first-hand the eternal cycles of Nature on a micro-scale for those who have the patience to observe, study and learn.