EXPLORING THE HOMELAND OF THE CHIRICAHUA APACHE IN SOUTHWEST NEW MEXICO

PART 1 OF 2

The cultural history of the Spanish and the later Anglo-American incursion and settlement of Southern New Mexico, Southern Arizona and the Northern Mexican States of Chihuahua and Sonora between the late 1600s and 1886 is inseparably linked and intertwined with that of the indigenous Native American Apache. At its core, this history has a common theme, one repeated countless times since the first European contact with New World in 1492. The theme, of course, is the familiar pattern of discovery, expansion, and exploitation, followed by conflict, defeat, and, ultimately, the domination, assimilation, or elimination of one culture by another.

However, unlike in much of the United States, where ever-expanding development and population has largely obliterated the scene of these events, the cultural history of Southwest New Mexico is still readily visible and waiting to be experienced first-hand by any visitors who find it of interest. The reason for this is two-fold: one, over half of the vast desert and mountainous landscape of Southwest New Mexico remains in Federal and State ownership, open to the public and essentially untouched by development; and two, most remaining private land of this area exists as undeveloped ranch land, little changed since territorial days. Consequently, for the person who enjoys being an up-close-and-personal witness to history, in the same environment of where, when, and how this epic cultural clash occurred, the trails and tales of the Southwestern New Mexico frontier are there for the reliving.

Situated on the edge of the Gila Wilderness, Casitas de Gila Guesthouses is located essentially in the heart of the homeland of the Chiricahua Apache. No matter where you hike or which natural attractions you visit while staying at the Casitas, you will come across sites where Chiricahua and Anglo-American or Mexican cultures collided during the 1800s.

Countless books and numerous films and documentaries have recorded this pageant of Southwest history, ranging from the mostly-fictional to the carefully-researched, factual accounts. A few of the more factual references are listed at the end of this blog, plus a favorite movie, which will provide the would-be traveller and explorer of Southwest New Mexico with an exciting preview of what can be experienced here. Of particular importance, and highly recommended, are the three volumes on the Chiricahua by historian and writer Edwin R. Sweeney, whose meticulous research and writing has provided much of the detailed information in this blog.

THE CHIRICAHUA APACHE

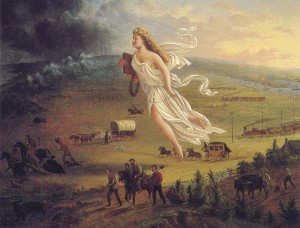

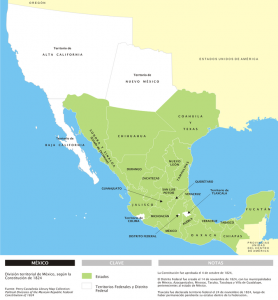

With the signing of the Treaty of Hidalgo on February 2, 1848, ending the Mexican-American War of 1846-1848, the United States was ceded vast areas of Mexico through the Mexican Cession, consisting of all of the present-day states of California, Nevada, most of Arizona, half of New Mexico, and portions of Colorado and Wyoming. Five years later, on December 30, 1853, the Gadsden Purchase was signed, in which the United States purchased from Mexico the remaining portions of what are now Arizona and New Mexico along their southern borders with Mexico. The American Southwest was now complete, and with it, or so its proponents thought, the widely-held belief in the Manifest Destiny of America’s westward expansion could now progress unthwarted and unrestrained. Unfortunately, there was still one remaining “problem”; a problem which would thwart, restrain, and shape the unfolding destiny of the American Southwest for the next 30 years … This problem was the Chiricahua Apache.

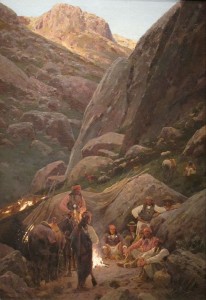

The question of just when the Native American culture known as the Apache migrated into the American Southwest from their northern origins is still open. Some scholars say the late 1500s; others say they were already living in New Mexico and Arizona in the 1400s. A chronicler with the Coronado Expedition of 1540-42 called what was to become Southeast Arizona and Southwest New Mexico the “desplobado”, or uninhabited land, reporting only long abandoned stone and adobe pueblo sites of habitation, which today we know were occupied by the Ancient Pueblo culture and vacated about a 100 years before Coronado passed through. Whether or not the Apache were present in the area at the time of Coronado is also an open question. However, there is no disagreement that it was the Apaches who were the dominant and controlling human presence within the vast, largely unpopulated desert and mountainous landscape of Southwestern New Mexico, Southeastern Arizona, and the northern half of the Mexican States of Sonora and Chihuahua by the 1700s and early 1800s. This was the homeland of the semi-nomadic Chiricahua Apache, a land often referred to as Apacheria.

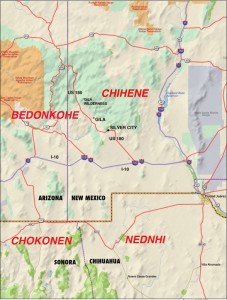

The Chiricahua Apache consisted of four main bands: the Bedonkohe, the Chihene, the Chokonen, and the Nednhi. These bands were loosely affiliated, intermarried, and lived for the most part in separate but adjoining areas of what is now Arizona, New Mexico, and northern Mexico. This vast area can be roughly divided into four geographic quadrants delineated by the modern day features of an east-west line along Interstate I-10 in Arizona and New Mexico, and a north-south line consisting of U.S. Highway 180 in New Mexico and its extension south of the U.S. Border along the Sonora and Chihuahua state line in Mexico. Using these geographic landmarks, the Bedonkohe would be found living in the northwest quadrant (north of I-10 and west of US 180), the Chihene would be in the northeast quadrant (north of I-10 and east of US 180), the Chokonen would be in the southwest quadrant (south of I-10 and west of US 180 and the Sonora-Chihuahua state line), and the Nednhi would be in the southeast quadrant (south of I-10 and east of US 180 and the Sonora-Chihuahua state line).

EARLY CONFLICT BETWEEN THE CHIRICAHUA AND NEW SPAIN AND MEXICO FROM THE 1600s to MID-1800s

Beginning in the 1600s and continuing until the mid-1800s, the Chiricahua were at war with the expanding Spanish presence in what was first a part of northern New Spain and later Mexico, after Mexican independence in 1821. This period was an on-going, tumultuous, and chaotic time in this vast desert and mountain landscape, encompassing what is now Sonora and Chihuahua States and the northern province of New Spain and Mexico, known at the time as Santa Fe de Nuevo Mexico, which eventually became New Mexico and Arizona in the United States.

To the Apache mind, this land was theirs by heritage, given to them by their Creator, Ussen. While initially the Spanish incursion was tolerated, it was only a matter of time before conflicts arose because of the proliferation and expansion of Spanish agricultural and mining settlements and the Chiricahua began their enduring campaign to drive the settlers out. Year after year, decade upon decade, Chiricahua raids upon the expanding towns, villages, ranches, mines, and commerce to take cattle, horses, property, and human life were merciless and unrelenting. In return, these raids would, of course, instigate coordinated military reprisals by Mexican authorities against the Chiricahua. Attack, revenge, and counter attack were a perpetual way of life. Periodically, however, the conflicts would cease temporarily in local areas when treaties would be made between the Mexican government or local authorities and the Chiricahua. Typically, these treaties would involve an arrangement in which the Chiricahua would agree to live in peace near the settlements in return for rations of food and clothing. Virtually all of these peace treaties were of short duration, ending abruptly with some facet of the treaty being broken and both parties returning to the next cycle of attacks and retaliation. And so it went for over 200 years!

COPPER BREEDS CONFLICT

Up until the early 1800s most of the conflict was confined to the provinces of Sonora and Chihuahua, with the Chiricahua often retiring to safe havens in New Mexico and Arizona Territories between depredations south of the Border. Perhaps one of the more significant developments during this time concerned the Chiricahua’s relationship with owners of the Santa Rita del Cobre Mine (Saint Rita of the Copper), at what is now the Chino Mine (Chinaman Mine) at Bayard, New Mexico, located 15 miles east of Silver City, and operated today by Freeport-MacMoRan Copper and Gold Company.

The history of the Santa Rita del Cobre mine is long and fascinating. The story begins in the year 1800, when an Apache Indian showed Spanish officer Lt. Colonel Jose Manuel Carrasco the site where the Apaches had been mining pure veins of native copper for many years. Lacking knowledge in mining, Carrasco sold the mine, which he had named Santa Rita del Cobre, to Francisco Manuel de Elguead in1804, who mined the deposit with convict labor. Many thousands of tons of pure copper were extracted from these early workings. The ore was then transported by mule train to Chihuahua, where it was made into coinage. During the 1820s and 1830s the mine was managed by Americans Sylvester Pattie, James Kirker, and Robert McKnight. While Elguead had many problems early on with Chiricahua raids and had to build a fort or presidio to protect his men, these problems disappeared when the Americans came into management. According to a number of reports from the times, it seems that Kirker came up with the idea of selling the Chiricahua rifles, ammunition, and whiskey in return for livestock taken during their raids in Sonora and Chihuahua! Kirker’s support for the Chiricahua campaign seems to have gone significantly further in that contemporary reports indicate his able-bodied presence and participation in some of the Chiricahua raids in Mexico.

A BOUNTY ON CHIRICAHUA SCALPS

In most cases the Mexican military forces proved ineffectual in dealing with the lightening-swift depredations of the Chiricahua, with the result that local militias were set up within towns and communities, encouraged and aided by the legislature of Sonora, which in 1835 established a bounty for each Apache scalp turned in. For the Mexican government these were desperate times; if the Chiricahua could not be turned to peace by force, then complete extermination would be pursued. By December 1839, raids in Chihuahua had become so bad that a private army of mercenaries was set up, to be funded by a tax on local businesses. The mission of this army was brief and stark: hunt down and kill or capture all Apaches possible. Contracted by the Chihuahuan government, who in 1837 had also enacted a law offering a bounty on Apache scalps, this army consisted mainly of American traders and trappers, Mexicans, escaped black slaves, and a number of Delaware and Shawnee Indians, and was led by none other than the same previously-mentioned, Irish-American mine manager, entrepreneur, and opportunist extraordinaire: James Kirker.

Kirker’s operations against the Apache were initially not that effective, and if anything, served to increase the number of Apache raids. At one point his contract was retracted, but renewed in 1846. It was on July 7th of that year that the Massacre at Galeana, Chihuahua, took place. Under the protection of a treaty, a large group of peaceful Apache men, women and children, mostly Chokonens and Nednhis, were invited to a feast. Reportedly, great quantities of mescal (a potent alcoholic drink made from the agave plant) and whiskey were provided to the Chiricahua guests. According to Chiricahua accounts, by the morning of the next day most of their people were in a drunken stupor, at which time Kirker’s men, aided by local Mexicans, slaughtered 130 of them, taking their scalps for bounty, which were reportedly then put on display in Chihuahua City. This horrific event would live in the Apache mind forever, and served to inflame Apache distrust, hostility, and hatred for all Mexicans in general, and soon Anglo-Americans as well, resulting in wars of vengeance for years to come, not only in Mexico but throughout the vast New Mexico Territory as well.

THE DISCOVERY OF GOLD AND SILVER IN SOUTHWEST NEW MEXICO

With the end of the Mexican-American War and the enactment of the Mexican Cession and the Gadsden Purchase in 1853, the floodgates were now opened for expanded Anglo-American presence and settlement in the New Mexico and Arizona territories. Major deposits of gold and silver were soon found in what is now Southwest New Mexico. These would eventually develop into several prosperous mining districts located in Grant and Catron Counties in Southwestern New Mexico. With the discovery and development of these mineral deposits, the safe-haven of the Heartland of Apacheria was to be forever changed as wave after wave of prospectors, ranchers, and settlers poured into the area.

In May 1860, a significant gold deposit was discovered in what was to become Grant County at the headwaters of Bear Creek in southwestern New Mexico Territory, some 20 miles upstream from Casitas de Gila. This deposit was discovered by three prospectors: Henry Burch, Jacob Snively, and James W. Hicks. They made the discovery while panning their first shovelful of dirt from a tributary of the Gila River which Snively named Bear Creek. Word of the discovery spread quickly and prospectors flocked to the area. By September of that year in a letter to the Mesilla Times published on October 25, Snively reported that between 500 and 1000 men were prospecting and engaged in mining in the surrounding area, both in placer and hard rock deposits. By the 1880s and 1890s, the Piños Altos Mining district had become a bustling boom town.

In 1870, a large deposit of silver was discovered near the old Spanish settlement of San Vincente de Cienega (Saint Vincent of the Marsh), about 7 miles southwest of Pinos Altos, and 25 miles south of Casitas de Gila. This silver discovery led to the founding of Silver City in the same year. Over time, Silver City became the commercial hub for all mining activity throughout the area.

By the late 1860s, 70s, and 80s, gold, silver, copper, and other minerals were being mined extensively throughout the north-south chain of the Burro Mountains, which lie about 10 miles west of Casitas de Gila.

With the discovery of gold and silver on Mineral Creek, in what is now Catron County, by Sergeant James C. Cooney in 1870, the gold rush was also on in the Mogollon Mountains, about 35 miles north of the Casitas. By the 1880s some 300-400 souls were mining the rich veins surrounding Cooney Camp. In time it was found that the veins extended to the south into the next drainage of Silver Creek, where eventually the mining town of Mogollon was established in 1889. The veins were larger and richer here, to the extent that by the early 1900s Mogollon boasted a population of 6,000 to 8,000 people seeking their fortune from the mines.

EARLY CONFLICT IN THE NEW MEXICO TERRITORY 1848-1861

During the Mexican-American war the Chiricahua allowed the U.S. Army safe passage through what was to become Southwest New Mexico to fight the Mexicans, ascribing to the old adage “the enemy of my enemy is my friend”. With the close of the war and the acquisition of the Mexican Cession in 1848, a peace treaty was signed between the U.S. and the Chiricahua, but shortly broke down as inevitable conflicts broke out between the Chiricahua and some of the thousands of prospectors, miners, and settlers. In 1851 the great Chihene Chiricahua Chief Mangas Coloradas was allegedly attacked by a group of miners near Pinos Altos, tied to a tree and severely flogged. Numerous subsequent violations of the treaty resulted in the inevitable Chiricahua reprisals. One particularly egregious event occurred in December 1860, when 30 miners conducted a surprise attack on a group of Chihene Chiricahua east of Pinos Altos, killing 4 and capturing 13 others. Then, on January 27, 1861, the infamous Bascom Affair occurred in which the great Chokonan Chief Cochise and members of his family were captured at Apache Pass in the Chiricahua Mountains under duplicitous circumstances by Lt. George Bascom and a large force of of U.S. Infantry. Cochise escaped, but in subsequent days Cochise’s brother and two nephews were hanged by Bascom’s forces. It was this event that precipitated the following 12 years of Cochise’s War. It was also shortly after the Bascom Affair that Mangas Coloradas declared war on the Americans himself, joining forces with his son-in-law Cochise.

THE GILA RESERVE APACHE RESERVATION

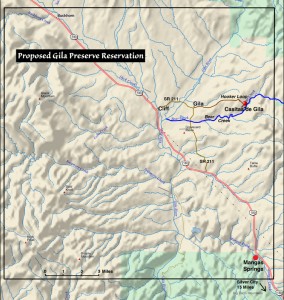

In 1849, 31-year-old Dr. Michael Steck went to New Mexico as a contract surgeon with the U.S. Army. In 1854 he was appointed Indian Agent for the Southern Apaches, as they were called at the time, who would now be considered primarily Chiricahua. Steck set up his agency near Ft. Thorn, a settlement and army outpost on the Rio Grande, near the present-day town of Hatch, NM. Unlike many of the Indian Agents appointed in these early days of the Southwest, Steck was an honest, hard-working official sincerely dedicated to his two-fold mission of looking after the well-being of the Apache and maintaining the peace between the Apache and the increasing influx of miners and settlers to the area. Responding to the mood and policy of the U.S. Government at the time, in 1859 Steck suggested the establishment of a reservation to which the Gila Apaches, including the Mogollon and Mimbres bands of the tribe (today considered the Bedonkohe and Chihene bands) would be moved. The reservation would comprise 225 square miles, or 144,000 acres of land, 20 miles or so northwest of Silver City. The proposed reservation would commence at the Southeast Corner at Santa Lucia Springs, and run North 15 miles; then West 15 miles; then South 15 miles; then East 15 miles to the place of beginning. Santa Lucia Springs is now known as Mangas Springs or Mangus, in a fertile valley located along U.S. Highway 180 just 8-1/2 miles south of Casitas de Gila Guesthouses.

During the days of Mangas Coloradas, a Bedonkohe Apache by birth but also a highly-influential leader to the Chihenne in his lifetime, Santa Lucia Springs is reported to have been a favorite place for large tribal gatherings of both Bedonkohe and Chihene. It is one of the few places in the area where copious amounts of water spring from the ground over a large area within a large, extremely fertile valley. These springs are dependable on a year-round basis, even during periods of extended drought.

Steck’s proposal for the reservation was approved by the Department of the Interior’s Office of Indian Affairs on May 14, 1860, thereby creating the Gila Preserve Indian Reservation. With this approval, the land proposed by Steck was removed from public domain status by the General Land Office, which meant that the land would not be available for settlement under the Homestead Act or other subsequent use.

But it was not to be.

Before plans for the Gila Reserve could be implemented in 1861, the War Between the States broke out, and by the time it was over, plans for the reservation were abandoned and the land returned to public domain status. The reason, of course, was one that would be given frequently throughout the settlement of the West. Quite simply, by the end of the Civil War, the Mangas valley with its perennial source of water was considered much too valuable as agricultural land for an Indian reservation, plus the surrounding mountains had already proven great potential for gold, silver, copper, and other minerals.

CASITAS DE GILA AND THE GILA PRESERVE RESERVATION

All of the land on which Casitas de Gila is situated, as well as all of the land that can be seen from the Casitas, was at one time part of a huge ranch put together over several generations by the pioneer Hooker Family. The first Hooker family in the area arrived in Silver City on New Year’s Day 1877 and later settled on the Gila River at the mouth of Bear Creek.

While we were constructing the Casitas in 1999, we were told several interesting stories about the history of the Hooker ranch and the Gila area by members of local families who had lived here all of their lives. One of the stories concerned a reservation for the Apaches that was to have encompassed all of Gila Valley, the communities of Gila, Cliff, and Buckhorn, as well as a large part of the old Hooker Ranch up on Bear Creek, but had never materialized. At the time we found the story interesting, but thought little more about it until a couple of years ago when we found a reference to the proposed Gila Preserve Reservation in “Cochise, Chiricahua Apache Chief” by Edwin R. Sweeney. We began researching the Gila Preserve, and eventually through the personal research of Ronald Henderson, a local historian and writer, were able to locate what is thought to be the point of beginning for the proposed reservation. After plotting out the reservation it became clear that all of the land on which Casitas de Gila is located would have indeed been within the northeast corner of the Gila Preserve Reservation boundary.

There is little doubt that the entire Bear Creek drainage was a favorite place for both the nomadic Chiricahua Apache, as well as for the earlier Mogollon Culture who farmed and built pit houses and sometimes cliff houses along its length. For the Bedonkohe Apache, it was a much used and loved part of their homeland territory and one that could be counted on for providing dependable water, abundant game, useful plants, a sheltered east-west corridor for rapid travel, and when necessary, a safe haven. Another of the stories locals told us concerns the jagged cliff-rimmed volcanic rock promontory that rises abruptly from the east side of Bear Creek and dominates the foreground as one looks north along the Creek from the front of the Casitas towards the mountainous ramparts of the Gila Wilderness mountains five miles distant. This spectacular erosional rocky remnant is now commonly known as “Turtle Rock”. However, some of the older ranchers recall when it was referred to as “Apache Corral”, a name surviving from earliest pioneer times when the high promontory provided an easily defended, natural fortress where older members, women and children of the tribe could be safely left when the able-bodied were conducting raids or war on their enemies.

Sitting here at the Casitas we sometimes contemplate how had it not been for the critical timing of the Civil War, all of the unfolding pageant of subsequent history within the greater Gila Valley area, from the days of the pioneers to modern times, including Casitas de Gila and all the guests that visit here, might never have never transpired, as this land would have remained forever the Gila Preserve Reservation for the Chiricahua Apache.

To Be Continued next month . . .

REFERENCES:

-

1. Edwin R. Sweeney, 1995, Cochise: Chiricahua Apache Chief, University of Oklahoma Press

2. Edwin R. Sweeney, 2011, Mangas Coloradas: Chief of the Chiricahua Apaches, University of Oklahoma Press

3. Edwin R. Sweeney, 2012, From Cochise to Geronimo: The Chiricahua Apaches, 1874-1886, University of Oklahoma Press

4. Eve Ball, 1988, Indeh: An Apache Odyssey, with New Maps, University of Oklahoma Press

5. David Roberts, 1994, Once They Moved Like the Wind, Touchstone

6. Geronimo and S.M. Barrett, 1906, 2005, Geronimo: My Life (Native American), Dover Publications. Geronimo’s autobiography as told in his own words to author S.M. Barrett while he was a Prisoner of War at Fort Sill, Oklahoma

7. Robert M. Utley, 2012, Geronimo, Yale University Press