2000 YEARS OF HARVEST TIME ALONG BEAR CREEK

HARVEST TIME AT THE CASITA GARDENS

It’s late August and the rains of the 2013 Southwest Monsoon season have shown no sign of weakening. As of this morning, Casitas de Gila Guesthouses has had 8.54 inches of rain since the monsoons began on July 1. Despite the devastating hailstorm of July 3, the courtyard garden at the house is thriving (except for the tomatoes, which were completely destroyed) and is now producing abundant yellow squash, basil, and green peppers for harvest, plus flowers galore. The over-composted soil brought up from the Bear Creek floodplain below the Casitas last year has obviously aged to just the right nutrient levels.

The large experimental garden put in this year down on the Bear Creek floodplain has also been highly successful. While most plants located at the periphery of the garden and some situated beneath the protective shade cloth where it ripped apart from the weight of the hail suffered significant damage by the July 3rd hail storm, those areas quickly regenerated new growth and soon caught up with the protected parts of the garden. Now well into the harvesting phase, the garden has produced abundant snap peas, string beans, carrots, and tomatoes. The delicata and butternut squashes, potatoes, and two kinds of watermelon should be ready for harvesting soon. The experimental plot of Einkorn Wheat has also done well, yielding a dense growth of two-foot high shafts of wheatberries now ripening golden in the late August sun. Only the cantaloupe have failed. They continue to put out long vines with lots of flowers, but, alas, only a few fruit, seemingly unwilling or unable to compete with the overpowering growth of the delicata and the butternut squash.

THE UNFERTILE SOILS OF THE CASITA FLATS AND THE FERTILE SOILS OF THE BEAR CREEK FLOODPLAIN

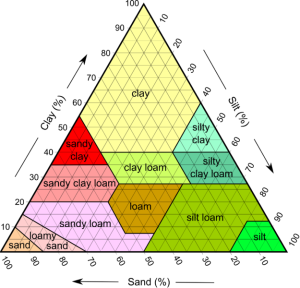

Productive agricultural soils consist of the right mixture of mineral particles (sand, silt and clay), water, gases, organic matter, and necessary nutrients which have developed over significant periods of time. The source of the mineral particles can be either igneous, metamorphic, or sedimentary rocks which have been broken down and altered by physical and chemical weathering at or near the surface of the earth. If the altered mineral material remains at the site where it was formed, on top of the parent rock, it eventually develops into what is known as a residual soil. Most soils, however, can be classified as transported soils, whereby the mineral particles are transported by the processes of water, gravity, wind, or ice, and then subsequently deposited. A third type of soil called cumulose soils are those that develop entirely from organic material that lives, dies, and collects in place such as peat or muck soils.

An essential form of both the mineral particles and organic matter in soil is the abundant presence of colloidal-sized particles (extremely fine particles between 2 and 500 nanometers). Colloidal particles act as storage repositories for essential nutrients and ions and act to stabilize soil chemistry through time and space.

Soils must contain sufficient nutrients in the right proportion in order to promote healthy and abundant plant growth. Some 20 elements are essential for plant growth and nutrition. Two of these, carbon (C) and oxygen (O) are taken in by plants from the air. The rest, including hydrogen (H) from water (H2O), are taken from the soil and are divided into four categories: the three primary macronutrients of nitrogen (N), phosphorous (P) and potassium (K); the three secondary nutrients calcium (Ca), sulphur (S) and magnesium (Mg); the macronutrient Silicon (Si); and the micronutrients/trace minerals: boron (B), chlorine (Cl), manganese (Mn), iron (Fe) zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), molybdenum (Mo), nickel (Ni), selenium (Se), and sodium (Na).

The soil comprising the flats on which the Casitas de Gila Guesthouses are constructed consists of materials transported down from the hills to the west of the Casitas by surface rainwater runoff, and ranges in thickness from 5 or 6 feet beneath the Casitas to about 20 feet at the west side of the flat. The soil on the flats consists mostly of silt to course sand with variable amounts of gravel derived either from the erosion of thin residual soil developed on the underlying weathered and altered Gila Conglomerate or physical erosion of unweathered Gila Conglomerate bedrock exposed over the surrounding hills.

Following the construction of the Casitas 15 years ago, numerous attempts were made at landscaping and gardening around the Casitas. These attempts included vegetable gardens, flower and herb gardens, and an orchard of fruit trees. While some of the efforts yielded results for a year or two, most ended in failure no matter what amount of physical effort was expended or advanced agricultural techniques, such drip irrigation systems, were implemented. Depending on the year, reasons for the these failures would be attributed to various scapegoats such as too cold and late frosts in the spring, too hot and a scorching sun in the summer, too little precipitation, too much wind, gopher attacks, grasshopper plagues, marauding deer, or even our own bad-acting horses. And, at first consideration, these were obvious and valid reasons.

Yet in retrospect, all of these reasons were for the most part secondary to a fundamental underlying cause, namely that the soil was extremely poor, too poor for the struggling plants to prevail against the various challenges that face all plant life in the American Southwest. Essentially the soil was almost devoid of necessary organic matter, nutrients, and especially, the critically-important colloidal clay mineral and organic particles. No, because of its extremely fine particle size, the bulk of the colloidal material, instead of being deposited over the flat with the coarser mineral particles, would be be swept along, suspended within the rushing runoff waters, across the flat, and then over and down the cliffs to be deposited either on the floodplain or to join with the waters of the creek itself some 80 feet below. With little or none of the critical colloidal materials which act to retain moisture and store nutrients, the small amount of nutrients in the soil would be quickly used up during the first or second year after an initial planting and could not be replaced from the mostly-sterile mineral soil remaining.

It was with this understanding, plus the personal aversion to using commercial fertilizers, that the decision was made to utilize the silty to fertile sandy loam from the Bear Creek floodplain terraces below. As related in the July 2013 blog and the opening paragraph above, the decision was a propitious one. The gardens flourished and good veggies were at last being enjoyed by all at the Casitas, (albeit somewhat reluctantly by Becky, who really much prefers chocolate!). And thus it also came to pass that the knowledge of how to grow food crops in Southern New Mexico was rediscovered by this writer, a body of knowledge that had been worked out in great detail by the Native American Mogollon Culture who were farming the Bear Creek drainage for hundreds of years some 2,000 years ago.

THE PRE-COLUMBIAN NATIVE AMERICAN MOGOLLON CULTURE

The Mogollon Culture was one of four essentially contemporaneous prehistoric Native American cultures that included the Anasazi or Ancestral Pueblo People, the Hohokam, and the Patayan cultures. These cultures thrived a huge area in the Southwestern United States and Northern Mexico that is sometimes referred to as Oasisamerica during the time period of roughly 1200-100 BC until 1300-1450 AD, a time span that has been subdivided into various eras under the Pecos Classification in the Four Corners area.

The large area in which the Mogollon Culture lived included Southern New Mexico and Southeastern Arizona in the U.S., plus Eastern Sonora and most of the Chihuahua states in Northern Mexico. Their cultural boundaries joined with the Hohokam Culture of Southeastern Arizona on the west and the Anasazi or Ancestral Pueblo Peoples Culture of the Four Corners area of Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico on the north.

The Mogollon Culture is thought to have developed from an earlier nomadic Archaic Culture called the Cochise around 150 AD, at which time pottery was introduced, probably from the south in Mexico. Over the years, archeological investigations of the Mogollon Culture have led to the recognition of several chronological phases in the development of the culture1, including:

- the Georgetown Phase, 550 to 650 AD, characterized by deep, round pit houses for living quarters, development of San Francisco Red, Alma series plainwares and San Lorenzo red-on-brown pottery

- the San Francisco Phase, 650 to 750 AD, characterized by shallow rectangular pit houses with rounded corners, continued production of San Francisco Red and Alma Series plainwares, plus the development of Mogollon red-on-brown and Three Circle red-on-white pottery

- the Three Circle Phase, 750 to 1000 AD, continued use of shallow rectangular pit houses with rounded corners, gradual replacement of San Francisco Red and Alma Series plainwares by Reserve Plain and Corrugated wares, plus development of the Puerco and Mimbres black-on-white pottery

- the Reserve Phase, 1000 to 1125 AD, pit houses giving way to surface pueblos of rock and adobe, development of the Reserve black-on-white pottery

- the Tularosa Phase, 1125 to 1300 AD, rectangular surface pueblos now the preferred building mode plus development of cliff dwellings, introduction of Tularosa black-on-white and some polychrome pottery

- the Mimbres Phase, 1025-1300, rectangular surface pueblos, some attaining large compounds of adjoining room blocks up to 150 or more rooms, development of the classic black-on-white Mimbres pottery which featured intricate geometric designs as well as figures of animals, birds, insects and humans

Starting in 1250 to 1300 and continuing until 1400 to 1450, the Mogollon people began to abandon the large pueblo complexes and disperse. Traditional explanations for this depopulation have centered on climate change, as evidenced by a 50-year period of extended and persistent drought that began in 1250. More recent investigations have considered outside pressures brought on by an influx of other Native American cultures with resulting conflict and warfare.

BEAR CREEK: AN ANCESTRAL HOMELAND OF THE MOGOLLON CULTURE

The mostly mountainous area enclosed by the Gila, San Francisco, and Mimbres rivers and their tributaries in Southwest New Mexico were heavily populated by the Mogollon Culture, and ruins of their early pit houses and later adobe and stone pueblo complexes and various cliff dwellings are found throughout the area. In the vicinity of Casitas de Gila Guesthouses, numerous village ruins and habitation sites are found along the Gila River near today’s communities of Cliff and Gila, upriver to the Gila Cliff Dwellings, and throughout the Bear Creek Drainage from its confluence with the Gila River at Gila upstream to its headwaters in Piños Altos. In the Bear Creek drainage, signs of the Mogollon Culture are especially abundant, including pit houses, small pueblo complexes, cliff dwellings, occasional petroglyphs, and sites of intense and extended agricultural activity, as evidenced in small caves and on bedrock surfaces along the creek that contain abundant mortar holes in which maize, acorns, and other harvested wild seeds were ground.

The Mogollon Culture depended on farming, supplemented by hunting and gathering, as a way of life. Like the Anasazi, Hohokam, and Patayan Cultures, they employed what is known as Three Sisters Agriculture, a type of farming used by many North American Native American cultures in which maize (corn), squash, and climbing beans are planted in close association. When planted in this manner, these three plants have a unique symbiotic association with one another. The maize provides a pole for the beans to climb on, the beans provide nitrogen to the soil that the maize and squash utilize, and the squash spreads out horizontally covering the ground with big leaves that retard weed growth and retain ground moisture.

FARMING THE STREAM TERRACES ALONG BEAR CREEK

Having spent some 15 years on foot and horseback studying, observing, and researching the natural and cultural history of the Bear Creek drainage, it seems highly probable that most if not all of the lower stream terraces bordering Bear Creek and the active floodplain were farmed by the Mogollon peoples during the thousand years or so that they lived here. On Bear Creek these terraces occur at elevations of 5 to 10 feet above normal creek level and range from a few feet to several hundred feet in width. The typical composition of these terraces is that of an organic rich, fine-grained silty and sandy loamy soil which accumulated over time from repeated deposition from sediment laden flood waters that overflowed the main channel and spread across the floodplain. As the flood waters spread out across the floodplain, the velocity of the water slowed, allowing the suspended fine sediment and organic debris to settle out and be left behind as a new thin layer of soil over the floodplain. It is this process operating repeatedly year after year down through the ages that produces the thick stream terrace deposits of organic rich, loamy soil that the Mogollon People farmed so long ago along Bear Creek.

Once formed, these stream terraces may persist for decades or even hundreds of years, or may be eroded away depending on the local action of the never-ending process of stream migration. In stream migration, the main channel of a stream constantly meanders or shifts back and forth in broad loops across the floodplain as it seeks to maintain a dynamic state of equilibrium between the sediment being transported and the velocity of the stream. As the channel meanders across the floodplain, it will often cut away the stream terraces that have existed for many decades. In other places it will bypass a stream terrace for a sufficient length of time to allow the downward cutting of the entire canyon bottom to be lowered sufficiently so that the terrace is left at an elevation high enough above the creek that even the largest floods will no longer inundate it.

The garden that was put in below the Casitas this year is located on a terrace some five to six feet about the present level of the creek. Presently about 100 feet in width, this terrace was at least 50 feet wider when the Casitas were built in 1999. As described in the June 20, 2013 blog the big flood of 2005 caused the main channel of Bear Creek to shift from the east side of the floodplain to the west side. In the process a large part of the east side of the terrace where the garden is now located was cut away. Over the next couple of years the cut bank of the terrace was stabilized by new growth of cottonwood and willow. Today the cut bank at the edge of the terrace is completely stabilized and protected from further erosion by a continuous row of shrubs and trees up to 50 feet in height. From time to time major floods will spread out across the terrace to deposit a new layer of fine nutrient rich loamy soil gradually raising the level of the terrace surface ever higher.

It is unlikely that the terrace on which this year’s garden was planted existed at the time of the Mogollon Culture, but rather is a product of stream deposition in much more recent times, probably within the last 100 to 200 years. However, just a few feet to the west of the garden, the surface of this modern stream terrace rises abruptly four to five feet to another level surface that extends westward several tens of feet to terminate against water-worn cliffs of Gila Conglomerate that form the west side of the Bear Creek Canyon. This higher level surface, now vegetated with old growth juniper, oak and mesquite, is a remnant portion of a much older stream terrace that can be traced along Bear Creek throughout much of the Casitas’ property. Evidence from personal research conducted to date on this ancient terrace indicates that it not only existed at the time of the Mogollon Culture, but that it was probably farmed by them as well.

During the initial development of the Casita property a small access road was constructed to the edge of the Bear Creek floodplain, terminating at the edge the ancient Bear Creek terrace just described. In the process of doing so, numerous rocks left in the path cut by the bulldozer were personally cast aside under nearby trees. About three years ago, while hiking the Casita trails, one of our guests picked up a rock off to the side of the terminus of this road and noticed that it showed evidence of having been worked. Indeed it had been. Examination suggests that the artifact had been quickly and roughly worked into a maul or adze-like shape with medial grooves for attachment of a handle. When shown the location of where the artifact had been found, it turned out that it was one of the rocks that had been scraped up from the ancient terrace at the end of the road during construction and cast aside under the trees 15 years ago!

CULTIVATED FOOD CROPS AND WILD EDIBLE PLANTS USED BY THE MOGOLLON PEOPLES

Most information that is written for general consumption concerning the lifestyle of the Mogollon People will start out by mentioning that they cultivated and depended upon the Three Sisters crops of maize, squash, and beans, which they supplemented by hunting and gathering. Typically, however, that’s about as far as these articles go. For the curious sort of person, and especially one who had just expended considerable amount of time and energy on an experimental garden down along Bear Creek, however, several inevitable questions soon began to pick away in one’s brain as to just what kind of squash and beans and corn were they growing, and what sort of plants might they have been gathering. Fortunately, there is a vast body of information available regarding these questions residing in the numerous in-depth archaeological studies that have been done on the Mogollon Culture over the past 80 years or so. But it does require a bit of digging (unearthing maybe?) to get it. Sorry … Anyway, here are some answers to those questions, gathered from two reports published in 19562 and 19863.

The 1956 report by Martin, et al, Higgens Flat Pueblo, Western New Mexico, details results of excavations done in 1953 on a Tularosa Phase Mogollon Pueblo village site located near Reserve, New Mexico, dating from about 1200 to its abandonment around 1250. Considerable identifiable plant remains of both cultivated and wild plants were recovered at this site from partially burned or charred material, which are summarized below. Wild plants identified in these studies and which are listed below as being used for food or medicinal purposes have been researched against the University of Michigan at Dearborn’s Native American Ethnobotany Data Base, an excellent reference source for those readers interested in learning more about how Native Americans have used various species of wild plants throughout history.

Cultivated food plants:

- Corn (Maize), specific name Zia mays: The bulk of the preserved plant material was corn and considerable research is presented comparing the Higgens Flat corn types to other varieties found at other Native American sites in the Southwest based on cob and grain measurements

- Squash, genus Cucurbita: Two types of squash, identified by seeds, were cultivated at Higgens Flat. Most abundant were seeds of a cultivated variety of Curcubita pepo, which at the time of the study was still being farmed by many Native Americans throughout the southwest. Today there are many cultivars of this species including Acorn, Delicata, Yellow Summer Squash, and Zucchini, as well as some winter squash.

Second in abundance was a variety of Cucurbita argyrosperma, syn. C.mixta Pangalo which at the time of the report was still being farmed by the Hopi and at Taos pueblo, a cultivar known as the Green Striped Cushaw. This species includes numerous cultivars of pumpkin and winter squash.

- Beans, genera Phaseolus and possibly Canavalia: Two species of Phaseolus were identified, P. vulgaris, the Common Bean or Kidney Bean, and P. acutifolius var. latifolius, the Teparary Bean. A large third type of bean was identified as possibly being either P. lunatus, the Lima Bean, P. coccineus, syn. P. multiflorus, the Scarlet Runner Bean, or Canavalia ensiformis, the Jack Bean, all three of which have been found at sites in central and southern Arizona.

Wild food or medicinal plants:

- Utah Juniper, Juniperus osetosperma, syn J. utahensis: berries.; used as medicine

- Arizona Walnut, Juglans major: nuts; gathered for food

- Freemont’s Goosefoot: Chenopodium fremontii, a member of the Amaranthaceae family: seeds; leaves and stems used as vegetable greens and seeds as grain in bread and porridge

- Cactus, Oputnia sp.: fragments of pads; pads and fruits used for food

- Jimson Weed or Sacred Datura, Datura wrightii, syn: D. metelodies Seeds; used as medicine and as hallucinogenic drug

The 1986 report by Anderson, et al, The Archaeology of Gila Cliff Dwellings, is a report that analyzes, synthesizes, and interprets existing field research data, excavations and collections made on the Gila Cliff Dwellings since the time of their discovery in the late1800s. As presented in this report, the Gila Cliff Dwellings, like the Higgens Pueblo site near Reserve, were constructed and occupied during the Tularosa Phase of the Mogollon Culture and housed some 40 to 60 people during a short period from roughly 1270 until 1290. Cultivated and wild plants used for food and medicinal purposes recovered and identified from the Cliff Dwellings include all of the plants listed from the Higgens Pueblo, plus some additional ones which are listed below.

Cultivated food plants:

- Squash, Cucurbita moschata: This species includes cultivars of both squash and pumpkin. Modern day cultivars include the Butternut Squash

Wild food or medicinal plants:

- Wild or Spotted Bean, Phaseolus maculatus, syn. P. metcalfei: used both as food and as medicine

- Wooton’s Devil’s Claw, Proboscidea parviflora or Hollyhock Devil’s Claw: young pods and seeds used for food, and also used as medicine

- Pinyon, Pinus edulis: seeds used for food

CULTIVATED FOOD CROPS AND WILD EDIBLE PLANTS USED BY THE MOGOLLON PEOPLES ON BEAR CREEK

It is highly probable that the Mogollon Peoples who lived and farmed on Bear Creek cultivated and gathered all of the plants recovered and identified from the Higgens Pueblo and Gila Cliff Dwellings archaeological studies. It is also highly probable that these plants are only a small fraction of the large number of plants found within the Bear Creek drainage that were gathered for food or used for medicinal purposes. For example, this year one of the most common plants found throughout the Bear Creek drainage and surrounding area and known by its common name of Careless Weed or Pigweed, Amaranthus palmeri, has virtually taken over most of the ground surface surrounding the Casitas de Gila Guesthouses and has formed thick massive stands of up to five feet high down on the Bear Creek floodplain. It is known from other archaeologic and ethnobotanical studies that this plant was extensively gathered and used throughout Native American history as an important food source, the leaves and stems boiled or baked as vegetable greens, and the dried seeds ground for flour. Also this year, a fine crop of Wooton’s Devil’s Claw (Proboscidea parviflora) and Hollyhock Devil’s Claw (Proboscidea althaeifolia) are to be found both around the Casitas on the terraces below along Bear Creek.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

In preparing this blog, it also must be said that some possible insight may have been gained in understanding the hierarchy of horticultural success of the various plants tried in this year’s experimental garden on the Bear Creek floodplain terrace. As discussed earlier, of all the plants tried, only the cantaloupes failed to produce fruit in abundance, seemingly having been completely overgrown and outproduced by the neighboring Delicata squash cultivar of Cucurbita pepo and Butternut squash cultivar of Cucurbita moschata. A little research has shown that the cantaloupe, while it is a member of the Cucurbitaceae family, belongs to an entirely different genus and species, Cucumis melo var. catalupensis. Cantaloupes originated in Iran, India, and Africa, and were cultivated in Iran 5,000 years ago and in Greece and Egypt 4,000 years ago. Cantaloupe is not native to North America. Yet down in the Bear Creek garden, the two squash that were planted beside the cantaloupe, Curcubita pepo and Cucurbita moschata, belong to a genus that is native throughout the American Southwest, and are species that have been genetically adapting and thriving here on Bear Creek for over 2,000 years. No wonder they did so well!

REFERENCES:

- Power point presentation Beloit University: PPT Southwest Complex Societies – Oneonta

- 1956, Martin, Paul S., Rinaldko, John B., Bluhm, Elaine A., Cutler, Hugh C.,

Higgins Flat Pueblo Western New Mexico, Fieldiana: Anthropology, Volume 45, Chicago Natural History Museum - 1986, Anderson, Keith M., Fenner, Gloria J., Morris, Don P., Teague, George A., McKusick, Charmion, The Archeology of the Gila Cliff Dwellings, Western Archeological and Conservation Center, Tucson, Arizona, The Digital Archaeological Record