— A FASCINATING JOURNEY THROUGH A LANDSCAPE BORN OF

ANCIENT SUPER-VOLCANO ERUPTIONS TO OBSERVE THE FOREST’S

RECOVERY FROM THE GREAT WHITEWATER BALDY COMPLEX FOREST FIRE OF 2012

THE SHERIDAN CORRAL TRAIL DAY HIKE (GILA NATIONAL FOREST TRAIL #181)

The Sheridan Corral Trail (GNFT #181), also known as the Holt Apache Trail, is one of several trails providing easy-to-moderate day hikes of two or three miles length (one way) into the southwestern portions of the Gila Wilderness and the High Country of the lofty Mogollon Mountains. From the trailhead at the end of Catron County Road C054 and an elevation of 6,360 feet, Trail #181 heads northeast, gradually ascending over the next 1.9 miles to an elevation of 6,840 feet on Sheridan Gulch Creek, where it intersects with the North Fork Big Dry Creek Trail, GNFT #225, leading south to Skunk Johnson’s Cabin. At this junction, Trail #181 then turns north, following the creek another 1.4 miles up Sheridan Gulch, before beginning a steep 1,000 foot ascent over 1.1 miles of switchbacks to a junction with the Holt Gulch Trail, GNFT #217 at an elevation of 9,120 feet.

A MID-MAY HIKE UP THE SHERIDAN CORRAL TRAIL

May is normally a bright, dry, warm month with brilliantly clear night skies, one of the best months for visiting astronomy guests at Casitas de Gila Guesthouses. This year was an exception, however, with abnormal cloud cover, some rainy days, below average temperatures, and disappointingly cloudy skies at night. By mid-month the May New Moon was fast approaching, one of those special times of the year when the viewing of the dark skies at the Casitas is dependably at its best. Yet for this year it was not to be. With increasing empathy, the hosts at the Casitas watched as their regular astronomy guests were teased daily by forecasts of good weather to come, only to be thwarted by another night of uncooperative, cloudy skies. After several days of this, and an updated forecast that was calling for yet another day and night of cloudy weather, it seemed like a good opportunity for the hosts to suggest a change in plans. Perhaps this was the time to introduce these dedicated observers of the Heavens to a more down-to-Earth daytime experience of another of the Casitas’ special local attractions: a hike into the Gila Wilderness!

Striking off from the Sheridan Corral trailhead, the trail was followed eastward, gradually climbing up and along a ridge, passing through a landscape of mature high desert Piñon Pine (Pinus edulis) and Alligator Juniper (Juniperus deppeana) forest, with intervening open areas of various grasses, Beargrass (Nolina microcarpa), Desert Scrub Oak (Quercus turbinella), Banana Yucca (Yucca baccata), Parry’s Agave (Agave parryi), Sotol (Dasylirion wheeleri), and Pancake Prickly Pear Cactus (Opuntia chlorotica). This vegetation is typical of the south-facing and southwest-facing volcanic foothills of the Mogollon Mountains below 6,800 feet.

After about a half mile, the Sheridan Corral trail passes from the Gila National Forest into the Gila Wilderness. Here and there vast panoramas now opened before us, slowing our progress as we paused to survey the magnificent Mogollon Mountains in the Gila Wilderness looming ever closer in the East, and the wild, rugged San Francisco River Backcountry in the distant West. Beneath our feet, the trail crunched loudly as we passed over exposures of the diverse, colorful volcanic deposits of the ancient Mogollon and Bursum Super-volcano eruptions that had created this rugged Wilderness.

At about 0.85 miles into the hike, the character of trail abruptly changes as we entered a zone of burned forest resulting from the Whitewater Baldy Complex Forest Fire of 2012, and began a gradual descent into Sheridan Gulch Canyon. Here, and for the next 0.6 miles, the trail offered an interesting opportunity to observe the forest in its third year of regeneration from that immense fire that raged through the western portion of the Gila Wilderness between May 9 and July 31, 2012, burning over 297,000 acres to become the largest forest fire in New Mexico’s history. Broad vistas to the south across Sheridan Gulch Canyon showed clearly how the fire progressed from south to north across this rugged landscape, leaving behind charred runs of blacked snags with intervening areas of untouched forest. As the trail descended further into the canyon one noticed an accompanying gradual change in vegetation from the drier, grassy south-facing slopes of high desert Piñon-Juniper forest into a cooler, wetter and more complex riparian forest of Ponderosa Pine (Pinus scopulorum), Douglas Fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) and other Conifers, Arizona Sycamore (Platanus wrightii), Arizona Walnut (Juglans major), Emory Oak (Quercus emoryi), and Gambel Oak (Quercus gambelii).

At about 1.2 miles into the hike, the trail intersects the canyon bottom. Here, a small stream gurgled, beckoning us to stop and refresh among a colorful diversity of volcanic boulders in transit downstream from the high country peaks looming high above us. Bordering the stream, a lush, three-year-old bright green resurgent forest of many species and a scattering of incredible wildflowers including the bizarre blossoms of the Golden Columbine (Aquilegia chrysantha) now surrounded us, rising up in exuberant color and contrast among the somber, ghostly, gray and blackened still-standing snags of the former pristine forest now spiking into the sky high overhead. Ensconced in this surreal setting, large boulders of choice were quickly converted into stoney tables and chairs as lunch was rapidly consumed by the famished, with some of the party chatting quietly, others silently immersed in the palpable energy of a Wilderness in the process of rebirth.

With lunch under our belts, we pressed on. Still passing through the burned area, the trail crossed back and forth across the narrow floodplain over the next quarter of a mile as cliffs of diverse volcanic bedrock bordering the sides of the canyon pressed in closer to the trail. Here and there boulders and charred forest debris choked erosional chasms, produced by catastrophic storm runoff on the fire-denuded steep sides of the canyon, sliced down to the trail from above.

And then, at a point just 1.45 miles from the trailhead, and within a matter of just a few feet, the trail emerged from the burned area to pass immediately back into an unburned mixed conifer and deciduous forest. What a surprise and a delight it was to be back into the forest green! Ancient old-growth Ponderosa and Douglas Fir now bordered the trail, as if still standing guard after defending one of Nature’s fire-lines, beyond which the advancing inferno could not pass. Instantly, we were immersed in a whole new world of enduring life and color. Fascinated, we continued on, once more engulfed by the primeval beauty of the Gila Wilderness.

It was now getting late, and although the trail through the Wilderness green beckoned us strongly onward, at the 1.5 mile point into our hike, we reluctantly turned around. It was time to return …

THE GEOLOGY OF THE SHERIDAN CORRAL TRAIL

The Sheridan Corral Trail is located in the southeast corner of the Holt Mountain Quadrangle. This entire area of the Gila Wilderness is composed of volcanic rocks deposited from the Super-volcano eruptions of the Mogollon Caldera, 34 million years ago, and the Bursum Caldera, 28 million years ago. The Holt Mountain area has been the subject of considerable geologic investigation, most notably as reported in the 2006 New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources Open-file Digital Geologic Map and Report, OF-GM 120: A Preliminary Geologic Map of the Holt Mountain Quadrangle, Catron County, New Mexico, by Jim Ratte, Scott Lynch, and Bill McIntosh.

Ratte, et al. consider the Holt Mountain Quadrangle critical to the understanding and interpretation of the volcanic history of the Mogollon Mountains complex, and in the above-cited reference give an excellent summary of the interpreted geologic history of the Gila Wilderness. A pdf file is available on-line, and is highly recommended for those who would like a better understanding of how the Gila Wilderness came into being.

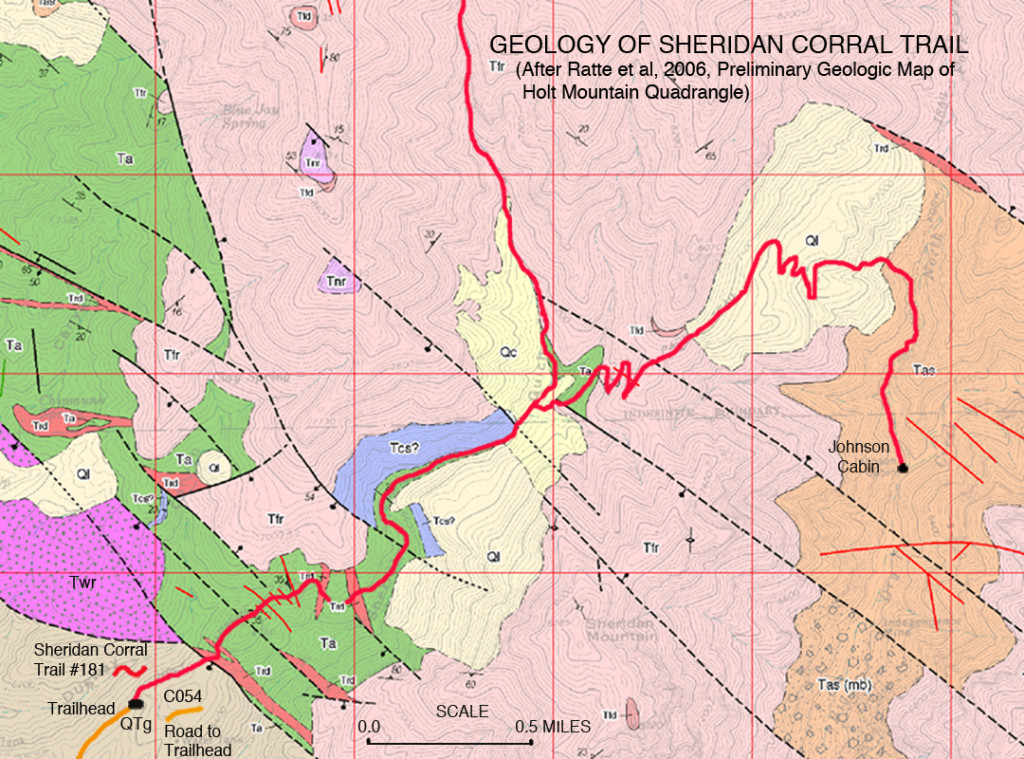

The map shown here (click on map for larger image) is a portion of Ratte et al’s Geologic map of the Holt Mountain Quadrangle with an overlay of the Sheridan Corral Trail. As shown, there are several distinct formations that have been identified and mapped in this portion of the quadrangle, that are well exposed along the portions of the Sheridan Corral as described in this blog. The various formations shown in Figure 1 are identified on the map by colors and symbols that are explained in detail in Ratte et al’s Geologic map of the Holt Mountain Quadrangle, which is available online in pdf format on the New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources web site. However, a brief description of the formations and rock types found along or very close to the section of the Sheridan Corral Trail as described in this blog are given below, starting at the Trailhead and progressing to a point 2.0 miles up the trail.

A BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF FORMATIONS AND ROCK TYPES FOUND ALONG THE FIRST TWO MILES OF THE SHERIDAN CORRAL TRAIL

Miles

0.0 Sheridan Corral Trailhead:

Qtg is the symbol for undivided deposits of the Gila Group which range from Miocene to Pleistocene in age. These are sedimentary rocks and loosely consolidated sediments composed of volcanic material carried by streams and rivers as gravel deposits from the ancestral Mogollon Mountains. Throughout the Gila Wilderness area, including the cliffs at Casitas de Gila, these rocks are informally referred to as the Gila Conglomerate.

0.25 Fault:

At this point the trail crosses a major normal fault that runs northwest along the face of the Mogollon Mountain uplift. Along this fault the Gila Conglomerate has been dropped down relative to the volcanic mountains, which have been lifted up. Although the fault zone itself is covered by loose sediment, its position would be very close to where the first exposure of bedrock is found on the trail after leaving the Trailhead.

0.25-1.20 Formations shown on Figure 1 — Twr (violet color), Tfr (pink), Trd (red) and Ta (green):

Twr is the symbol for the Wilcox Peak Rhyolite Formation of Eocene age, which is a fine-grained intrusive igneous rock of rhyolitic composition that is commonly found chemically altered as soft deposits rich in clay minerals such as dickite and other secondary minerals such as alunite. Analyses of alunite crystals have given an age for the Wilcox Peak Rhyolite of 33 million years, indicating that this formation was deposited during an eruption of the Mogollon Caldera.

Tfr is the symbol for the Fanney Rhyolite Formation of Oligocene age. The Fanney Rhyolite consists of light gray to reddish gray extrusive lava flows and intrusive domes around the ring-fracture zone of the Bursum Caldera which erupted about 28 million years ago.

Trd is the symbol for the Fanney Rhyolite Dikes which are vertical intrusive veins of various thickness that radiate off from intrusive domes of the Fanney Rhyolite.

Ta is the symbol for Andesite Lava Flows and inter-layered volcaniclastic sandstone beds of uncertain age relationships. They could be either Eocene or Oligocene in age, and possibly were erupted from the Mogollon Caldera.

1.20-2.00 Formations shown on Figure 1 — Tcs? (purple), Ql cream), and Qc (yellow):

Tcs Is the symbol for the South Fork Member of the Cooney Tuff Formation a deposit of Uppermost Eocene or Lowermost Oligocene age which was ejected from the Mogollon Caldera. The South Fork Member at its type locality near the mouth of Whitewater Canyon (The Catwalk canyon) consists of deposits of partially to densely welded ash flow tuffs. The question mark behind the symbol as it is mapped along the Sheridan Corral Trail means that these deposits are tentatively correlated with the South Fork Member deposits of Whitewater Canyon.

Ql is the symbol for Landslide Deposits of Pleistocene and possibly Holocene age that form extensive areas of slumped and rotated bedrock that came loose and slid down along the west-facing slopes of the Mogollon Range.

Qc is the symbol for Colluvium of Holocene age consisting of coarse talus and unsorted gravel deposits that mantle bedrock on steep slopes and some valleys of the Mogollon Range.

SOME FURTHER NOTES, SUGGESTIONS, AND CAUTIONS REGARDING THE SHERIDAN CORRAL TRAIL

This blog discusses conditions experienced on May 15, 2015, of only the first 1.5 miles of the Sheridan Corral Trail. Visual observation of aerial photography of the trail on Google Earth taken 2/22/13, indicates the next 2.5 miles of the trail to be relatively untouched by the 2012 fire, and therefore, should be suitable for an extended day hike. Recent discussions with Gila National Forest personnel at the Glenwood Ranger Station, based on their field examination of the trail following the fire, confirm this observation to be correct, and suggest that the trail should be in fair condition and easily followed, but that further on could become difficult to traverse and follow.

A cautionary suggestion is offered regarding current hiking on any of the Gila National Forest or Gila Wilderness trails that were previously heavily forested and subsequently burned during the Whitewater Baldy fire of 2012. Many of these trails, such as the burned portion of the Sheridan Corral Trail discussed in this blog between the .85 and 1.45 mile points, pass through and beneath large portions of dead standing timber. Now, three years after the fire, many of these dead standing trees have rotted at their core and are extremely susceptible to falling at any time, but especially during strong winds or running water during storms or flash floods. Although this blog discusses enjoying lunch in such a burned area, it is definitely not recommended! On that particular day the wind was calm, but had we known that the unburned portion of the trail would begin such a short distance ahead we would have continued further on before acquiescing to our growling stomachs! Keep safe!