OVERLOOKING THE GILA WILDERNESS IN SOUTHWEST NEW MEXICO

AT CASITAS DE GILA GUESTHOUSES

A VIEW FROM THE TOP

Hiking in Nature, regardless of where it is undertaken, is a simple pleasure that is always good for the body as well as the soul. However, there’s something uniquely special about completing a hike to the top of a hill or mountain that cannot be sensed when hiking in lowland terrains. It is an elusive something that transcends the descriptive word, a something that can only be perceived and experienced at the personal level. Elements of the reward at the top can be described, of course: the reward of a magnificent view, the psychological and physical satisfaction of having made it all the way to the top, the absolute silence and stillness of vast open spaces on a quiet day, or conversely, the bluster and buffeting of the wind as it rushes past one to the other side. But, yet, there is always something more, an ineffable something that strikes a deeper chord within one’s being, and that, once experienced, keeps drawing one up that beckoning hill or mountain again and again.

At Casitas de Gila Guesthouses there is such a hike, a mile-long trail that winds its way up a small mountain that rises up directly in front of the Casitas on the other side of Bear Creek. We call it “The Paradise Overlook Mountain Trail”.

THE GEOLOGIC SETTING OF THE PARADISE OVERLOOK MOUNTAIN TRAIL

Casitas de Gila is situated at the very edge of a series of cliffs that crop out along the west side of Bear Creek Canyon, a narrow, hundred-foot-deep canyon that has been incised into the 5 to 10 million-year-old Gila Conglomerate Formation. The Gila Conglomerate is a widespread sedimentary formation consisting almost entirely of volcanic rock and pyroclastic fragments that were eroded from uplifted volcanic rock formations formed by large-scale volcanic activity. This volcanic activity consisted of four extremely explosive, large, caldera-type eruptions, commonly known as super-volcanoes. These four super-volcanoes occurred within what is now the Gila Wilderness in two episodes that occurred 34 and 28 million years ago. Ancient rivers and creeks flowing out of these volcanic mountains over subsequent millions of years carried the eroded volcanic material downstream where it was deposited within adjacent down-dropped fault basins caused by tectonic subsidence to form the thick sedimentary layers of rock formations that are now called the Gila Conglomerate.

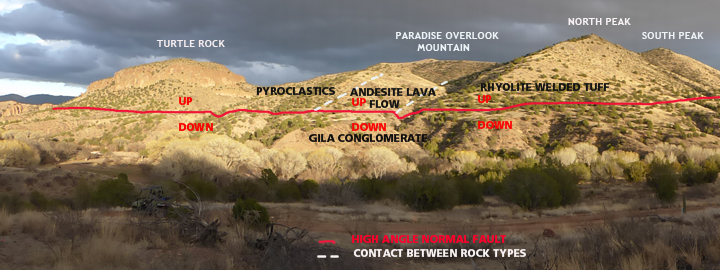

The mountainous terrain directly east of Casitas de Gila constitutes the western end of the Silver City Range, a 20-mile-long, uplifted fault-block range of mountains that extends northwest from Silver City to terminate on the east side of Bear Creek in front of the Casitas, where the mountain range is truncated by a major, north-south trending, high-angle, normal dip-slip fault. Close examination of this fault and the rock formations that lie on either side of the fault yields considerable information regarding the geologic history of rocks found along the Paradise Overlook Trail:

- The volcanic rocks comprising the small mountains and peaks east of the fault (Turtle Rock, Paradise Overlook Mountain, and North and South Peaks—see photo above) were ejected from the Bursum Super-Volcano caldera 28 million years ago, the center of which was located about 25 miles north of the Casitas. These rocks consist of an alternating sequence of primarily three distinct rock types, including, from oldest to youngest: rhyolite welded ash-fall/flow tuff, andesite lava flow, and various types of fine to coarse grained pyroclastic rock. Originally deposited in horizontal layers, these volcanic rocks were subsequently uplifted and tilted approximately 30° to the north during regional mountain building that occurred in Southwest New Mexico around 20 to 15 million years ago, which included the uplift of the Silver City Range.

- Following the uplift of the Silver City Range and other nearby mountains, the Gila Conglomerate was formed between 6 and 10 million years ago by numerous rivers and creeks carrying eroded material out of the mountains. This eroded material was then deposited in adjacent down-dropped fault basins such as the Gila River Valley, lying just to the west of the Casitas.

- Fault movement along the margins of these uplifted fault-block mountains continued for a long time as evidenced by the great thickness of the deposits of the Gila Conglomerate that are found throughout in the area, such as those now exposed along the cliffs of Bear Creek Canyon in front of the Casitas. The vertical cliffs as seen today across from the Casitas were carved and sculpted by the abrasive down-cutting action of sediment being carried downstream by the running waters of Bear Creek operating over many hundreds of thousands of years.

A MORNING’S HIKE UP THE PARADISE OVERLOOK MOUNTAIN TRAIL

Passing under the gnarled white branches of an ancient sycamore and then through a gate, the Paradise Overlook Mountain Trail immediately begins a steep climb to the north as it leaves the Bear Creek floodplain. Within a couple of hundred feet, outcrops of Gila Conglomerate surface here and there, exposed by the runoff from the previous summer’s Monsoon rains. After a short climb, the trail levels off just above the tops of the old cottonwoods lining the creek and the view to the west begins to open up. And what a view it is, as the entire southern front of the majestic Mogollon Range and the northern end of the Burro Mountains emerge from behind the low rolling hills that border Bear Creek to the west.

For the next hundred yards, the trail crosses a gently sloping surface of thick, clayey soil washed down from the mountain above. Previous studies in the adjacent Paradise Lookout Canyon 350 feet to the south of the trail have revealed that a few feet below this gently-sloping, soil-covered surface lies a smooth, flat terrace-like surface of Gila Conglomerate bedrock, cut hundreds of thousands of years ago by the running waters of an ancestral Bear Creek. At the eastern, upper end of the soil covered terrace, the trail steepens considerably once more, and begins a steady upward climb which will continue for most of the remaining hike up the mountain.

Immediately past the point where the trail begins to steepen, the thick soils covering the terrace disappear and fresh bedrock is exposed at the surface and sides of the trail. This bedrock, however, is not Gila Conglomerate, but rather a dark gray, very fine grained volcanic rock which is classified compositionally as andesite. Looking closely, one observes that much of the rock contains abundant spherical to ellipsoidal holes ranging in size from a millimeter to two or three centimeters or more, many of which are lined with white crystals of quartz and other minerals known as zeolites. These are gas bubbles formed when the rock was still in the molten state, and which offer mute testimony that the rock formed as a lava flow. The ellipsoidal gas bubbles show not only that the flow rock was still moving immediately prior to cooling and solidification, but with further detailed field analysis could indicate the actual direction in which the lava was moving at the time of deposition.

As often happens in doing geologic field studies, the nature of the contact between the sedimentary Gila Conglomerate underlying the terrace and the volcanic rock is totally obscured by the thick soils covering the bedrock, making it impossible to determine the age and spacial relationships between the two rock types. Fortunately, however, the contact is beautifully exposed 350 feet to the south in the bottom of Paradise Lookout Canyon. Here the contact is revealed to be a north-south trending, high-angle fault contact that dips to the west. Further examination of the rocks on either side of the contact show that as horizontal beds of the Gila Conglomerate are traced towards the contact from the west they gradually turn upward to intersect with the fault, clearly indicating that the block of Gila Conglomerate had moved down relative to the block of volcanic rock which had moved up (see photo).

Continuing on beyond the soil covered terrace, the trail soon comes to series of switchbacks where a new type of bedrock is encountered. These rocks are highly variable in composition and texture, consisting of a chaotic mix of dark reddish to gray rock fragments of various sizes and compositions welded together in a very fine grained, light gray to tan colored matrix. Closer examination reveals these are pyroclastic rocks that were explosively ejected when the Bursum Cauldera blew its top. While some of the exposures along this segment of the trail might be mistaken for Gila Conglomerate sedimentary rocks, the freshly broken, angular texture of most of the smaller fragments and the fact that these fragments are predominantly composed of the same rock type of fine-grained andesite indicate the volcanic pyroclastic origin.

Exposures of pyroclastic rocks alternate with highly weathered outcrops of the andesite lava flow rocks as the trail switchbacks across the contact between the two rock types. At this point, about halfway up the mountain, the soil cover is thin, generally only a foot or two thick over the bedrock on these mountain slopes. In many places along the trail it is easily seen that the soil has formed in place from the highly weathered and altered underlying bedrock.

Up to this point, the trail has been ascending the mountain along a steep slope on the north side of Paradise Overlook Canyon, a prominent canyon that drains from a topographic saddle between Paradise Overlook Mountain and North Peak, located a third of the mile to the southwest. Vegetation along this section of the trail is sparse due to the dryness of its south facing exposure and consists mostly of various grasses, Honey Mesquite, Wait-a Minute Bush or Catclaw, and Prickly Pear Cactus, with increasing stands of Sotol agave, as the trail climbs higher. Looking across the canyon to the south, however, one notices that the vegetation on the steep, north facing slope is considerably different. It is much denser with a greater diversity of plants, characterized by abundant One-Seed Juniper and Scrub Live Oak scattered over a thick grass-covered slope of various species that flourish there due to the greater retention of soil moisture on the north-facing slopes.

Two-thirds of the way up the mountain, the trail finally crosses Paradise Overlook Canyon to begin the steepest ascent of the trail up the north side of the canyon to terminate at Paradise Overlook at the top of the mountain. As the trail climbs ever higher on the mountain, the vista to the west becomes increasingly expansive, carrying the eye first across the Gila River Valley to Sacaton Mesa, then into the Gila Wilderness and the distant Blue Range Wilderness beyond.

Immediately upon crossing the canyon, one finds that the rock type has changed to a dense, hard, light tan to white fine-grained welded ash-fall or ash-flow tuff, the oldest of the three main volcanic rock type deposits found along the trail. Continuing up the final one-tenth of a mile, the welded tuff soon changes back to an alternating sequence of pyroclastic rocks that crop out along the trail, ranging from fine-grained welded tuffs, to medium-coarse pyroclastic rocks with mostly homogeneous angular fragments of fine-grained andesite, to complex pyroclastic aggregates of diverse volcanic rock types ranging from small angular fragments a centimeter or less in size to large, well-rounded boulders up to 30 centimeters or more in diameter of andesite and rhyolite many of which contain crystal-lined gas bubbles.

Trail across Turtle Rock to the entire southern flank of the majestic Mogollon Range

Near the top of the trail, a final short, but steep … yes, we can do it … switchback brings the intrepid hiker to a much-welcomed wide, flat spot in the trail where thoughtfully placed large boulders make for a nice resting and watering spot with a marvelous view. But, nice as this spot is, the best part of the trail is yet to come! On the north side of the flat spot a small rock cairn marks the beginning of a final 250 foot scramble to the very top of Paradise overlook Mountain. Here, at an elevation of 5,540 feet, some 800 feet above Bear Creek below, is the perfect lunch spot you’ve been waiting for, a spot where an incredible 360° view awaits. To relax here, looking out over the Gila Wilderness and the surrounding panorama in all directions, you most likely will agree that indeed it is a Paradise Overlook …