AT CASITAS DE GILA GUESTHOUSES

CYCLES OF SOLSTICE ON BEAR CREEK

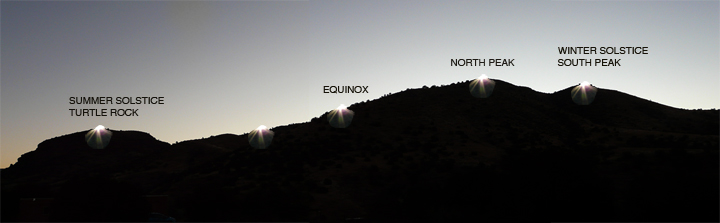

Guests that return to Casitas de Gila Guesthouses at different times of the year will observe, while sitting in front of their Casita watching the Sunrise, that the Sun comes up at different places along the mountainous skyline to the East above Bear Creek. In mid to late June the sun will appear to pause, popping up repeatedly and predictably for a few days from the same place behind Turtle Rock at the north end of the skyline. Then, as Summer fades and transitions into Early Fall, this anticipated shaft of Dawn’s first light begins its annual, daily southward migration, arriving at the middle of the skyline in late September. Without pausing, the southward journey of Sunrise continues for another three months until late December, when it finally comes to its southern-most point of emergence near the top of South Peak. Then, after another few day’s pause where it will be seen to rise in the same place, this first light of Sunrise will begin once more to trace its six-month-long journey northward along the skyline to finally again emerge from behind Turtle Rock.

This observed seasonal progression of Sunrise is, of course, as most of us were taught so long ago, due to the annual, year-long cyclical progression of the Solstices, from Summer Solstice to Winter Solstice and then return. The Solstices, along with the intervening half-way points the Equinoxes, mark the passage of the Seasons and the progression of the Earth in its orbit around the Sun. Because the Earth’s axis of rotation is tilted at an angle of about 23.43° relative to its orbital plane about the Sun, the angle at which the Sun’s rays strike the earth varies as the Earth proceeds in its orbit. Hence, for a person who enjoys a cup of coffee or tea while waiting for Sunrise at the Casitas, over a year’s time, she or he will observe that the exact position of Sunrise will shift back and forth with the Seasons along the mountainous horizon to the East, covering a horizontal distance of about 0.8 of a mile, between Turtle Rock and South Peak, at a rate, excluding the pauses around the Solstices, of roughly 26 feet a day.

ARCHAEOASTRONOMY AND THE ANCIENT ONES

For over 2,000 years, the three main Prehistoric Native American Cultures of the American Southwest — the Ancestral Puebloans (Anasazi), Mogollon, and Hohokam — farmed the river and creek valleys and upland areas of this arid landscape, with increasing dependance on the three main crops of corn, squash, and beans as their main source of sustenance. As these cultures moved away from small groups of hunter and gatherer populations living in individual pit house structures to larger and larger communities living in above-ground complexes of adobe and stone, their dependance on reliable and successful harvests of crops became increasingly critical.

To insure successful crops and harvests, each of these cultures employed their own intertwined, two-fold agrarian strategy, the first involving complex nature-oriented religious beliefs, customs, and ceremonies, and the second, in what might be considered a more scientific and practical approach, the study of the change in the seasons as related to movements of the sun, moon, planets, and stars in the heavens. Today, this prehistoric connection of cultures to celestial phenomena is the subject of the emerging multidisciplinary field known as archaeoastronomy.

As anyone knows who has ever planted a garden, the time of planting is critical. Put the seeds in the ground too soon in the Spring and a late frost will send you back to the seed store. Put them in too late and your harvest may be cut short or ruined by the onset of an early Fall or Winter. Even with today’s calendars, long range weather forecasts, endless internet resources, etc., the natural and cyclical uncertainties of weather from year to year ensure that there are no guarantees that a particular crop is going to be successful. Fortunately for today’s back-to-the-land horticultural enthusiast, there is always the backup of the local plant nursery or grocery store.

For Prehistoric agrarian cultures the world over, including the Mogollon, Ancestral Pueblo, and Hohokam cultures here in the Southwest, knowing the right time for planting was quite literally a matter of life and death. There were no backups or plan B should crops fail. And, while the prudent Mogollon agronomist would undoubtedly have held back seeds to be used in a second or possibly a third planting, several crop failures in a row could easily mean starvation. The need for a reliable indicator for the time of planting was essential. Throughout human history it has been proven time and time again that, indeed, necessity is the mother of invention. Thus it was, over a time span of several millennia, that many of these early agrarian cultures, quite independently of one another both in time and space, turned to the heavens for the solution to their problem of determining the time of planting. Through repeated observations gathered over generations of the recurring movements of the celestial bodies, they were able to devise and construct permanent and reliable indicators of stone, adobe mud, and wood that would indicate not only the time of planting, but also the summer and winter solstices, the equinoxes, and a variety of lunar events.

Examples of these early almanacs or calendars of stone, mud, and wood can be found the world over, from the Neolithic megalith monuments of Newgrange in Ireland and Stonehenge in England, to astronomical alignments of structures built by the Mayans and Incas in Mesoamerica, to the pictographic indicators and astronomical alignments of buildings at the Ancestral Pueblo People (Anasazi) Complex of Chaco Culture National Historical Park in Northwest New Mexico, and Wupatki National Monument near Flagstaff, Arizona.

It is clear from comparative research in archaeoastronomy and ethnoastronomy (the study of the heavens by historic and present-day indigenous cultures and societies) that down through the ages different cultures ascribed different meanings and interpretations to their observations of the heavens. Attempts at determining the deeper cultural context, significance, or purpose of the various archaeoastronomical alignments and indicators of prehistoric cultures that have been found and described is very difficult, resulting in conclusions that are generally considered speculative and subject to different interpretations. However, with respect to the use of these alignments and indicators by prehistoric peoples as a type of agricultural calendar to ensure successful planting and harvests, there is much greater consensus that such use was both essential and widespread in practice.

ARCHAEOASTRONOMY AT CHACO CANYON

The Ancestral Pueblo People Culture (Anasazi) Complex at Chaco Canyon in Northwest New Mexico is the site of numerous examples of what many, but not all, scientists and archaeologists now consider to be archaeoastronomical constructed alignments and indicators. It all began in 1977, when an artist by the name of Anna Sofaer visited Chaco Canyon as a volunteer to record Chacoan rock art in the form of petroglyphs and pictographs. During this work she discovered the now famous Sun Dagger Site on Fajada Butte, a prominent landform rising some 400 feet from the canyon floor at the south entrance of Chaco Canyon.

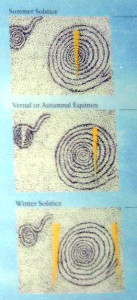

The Sun Dagger Site consists of three large stone slabs leaning against the cliff which focus sunlight in various patterns across two spiral petroglyphs pecked into the cliff wall. At about 11:30 AM on Summer Solstice a dagger of light pierces the center of the larger spiral which lies in shadow beneath the stones. At other times of the year different shafts of light mark the winter solstice and the equinoxes, as well as lunar events. Following this initial work, Sofaer went on to found the Solstice Project which resulted in a tremendous amount of research regarding numerous archaeoastronomical alignments of the many of the buildings in the Chaco Canyon Complex.

The image at right is a diagram of the Sun Dagger petroglyph at the Sun Dagger Site, showing Sunlight Daggers for Summer and Winter Solstices and Vernal or Autumnal Equinox.

EXPLORING THE UNIQUENESS OF NEW MEXICO LIGHT

There are several climatic, atmospheric, and terrestrial factors that combine to produce the unique light found in New Mexico. Primary and most important is the ubiquitous high-desert climate itself, characterized by predominately high barometric pressure, low humidity, and scant precipitation. Couple these factors with the extreme atmospheric clarity that results from the State’s small population and low levels of pollution, and the relatively thinner atmosphere due to the general high elevation of the landscape, and the result is the distinctive turquoise blue New Mexican Summer sky that gradually takes on the deeper shades of cobalt blue seen in Winter. And it is because of this atmospheric clarity that the full spectrum of undiluted, non-refracted or non-degraded frequencies of sunlight are allowed to penetrate and illuminate the iconic New Mexican landscape with such intensity and brilliance.

THE AMAZING LIGHT OF SUMMER SOLSTICE

As discussed in an earlier blog on Winter Solstice, there is a vast difference between the light and shadow illuminating the landscape of New Mexico during Summer Solstice as compared to that of Winter Solstice. The perceived intensity and brilliance of the New Mexico Sun varies along with the seasons in response to the angle at which the Sun’s rays strike the earth due to the tilt of the Earth’s rotational axis. In the Summer, when the Sun traces its daily passage high overhead, the sunlight in New Mexico is virtually omnipresent – penetrating, bouncing, and reflecting soft, warm, glowing light into the shadows of even the deepest canyons and thickest mountain forests. With the coming of Fall, however, as the daily arc of the Sun’s passage traces ever lower towards the southern horizon, the intensity of the direct sunlight gradually decreases. And with this decrease, one notices that the soft warm glow once reflecting within the shadows of the canyons and forests takes on a harder, cooler, dimmer, bluish tone, and that the contrast between light and shadow has increased markedly.

EXPLORING LIGHT AND SHADOW ON BEAR CREEK AT SUMMER SOLSTICE

MORNING LIGHT

This year, Summer Solstice 2015 occurred on June 20 at 16:38 UT or 10:38 AM MDT, and on this date Sunrise for Gila, NM, calculated on the basis of longitude was forecast to occur at 6:05 AM MDT. However, here at Casitas de Gila, because of the proximity of a mountainous skyline comprising Turtle Rock, North Peak, and South Peak on the other side of Bear Creek due east of the Casitas, on this morning from a viewing point beside the windmill, the Sun would not emerge from behind the highest point of Turtle Rock until 6:54 AM MDT. The day dawned clear and bright after an overnight low of 58° F. It was a beautiful First Day of Summer morning and a perfect time for a hike along Bear Creek to observe the light and shadow of Summer Solstice.

Hiking north out the entrance road to the Casitas around 7 AM, the One Seeded Junipers (Juniperus monosperma) were still casting long shadows across the road. Looking back to the south, the long ridge extending west from South Peak still remained in deep shadow behind the Casita buildings now bathed in brilliant sunlight streaming in from the east over Turtle Rock. Here and there the last of the Spring Flowers raised their heads to greet the morning rays: beside the road the bizarre, gaudy little blossoms of the Silverleaf Nightshade (Solanum elaeagnifolium) and to the west, up on the hillside, clusters of sun-glazed white spires of Soaptree Yucca (Yucca elata) flowers soaring high into the sky.

Heading down a dry wash towards the Creek, the Desert Willows (Chilopsis linearis) (immediately above) were just coming into flower, their orchid-like pink, purple and yellow flowers glistening in back-lighted brilliance against the long, drooping arcs of shadowed green leaves.

Leaving the dry wash behind, the Hidden Spring Trail intersects the Big Tree Trail on Bear Creek towards the north end of the Casitas land. Here, a thousand shafts of sunlight filtered down through the foliage of the high-rising stands of young Freemont Cottonwoods (Populus freemontii) on the east bank of the Creek, creating a creekside sylvan tapestry of light and shadow in a myriad of different shades and tones of lush, Sun-dappled green. The air was still and the silence complete, except for the frequent plaintiff calls of numerous unseen birds wafting down from overhead.

Continuing south along along the Creek, the Big Tree Trail passes beneath overarching branches of large, mature Goodding’s Willow (Salix goddingii) to soon enter a very dark and shadowed grove of Gray Oak (Quercus grisea) guarded by a sunlit curtain of tendrils of Canyon Grape (Vitus arizonicus).

The Sun is rising higher now; time to leave the comfortable hammock beneath the ancient Cottonwood and continue hiking south along the Creek. Once more the Creek itself is bathed in alternating bands of light and shadow. The banks along the Creek’s edge are lined with moist-ground-loving flowering plants such as the beautiful Spotted Monkeyflower (Mimulus guttatus) (below left) and the exquisite stout and furry blooms of Rabbitfootgrass (Polypogon monspeliensis) (below right) ablaze in the light of the Solstice Sun.

Approaching the cliffs, the stream channel narrows. Dense stands of tall Cottonwoods, Bluestem Willow (Salix irrorata), Seepwillow (Baccharis salicifolia), and occasional Arizona Sycamore (Platanus wrightii) press in on the boulder-strewn channel, casting the creek in deep mid-morning shadow, except where sporadic shafts of brilliant sunlight penetrate the foliage above to illuminate, without giving reason, that which Nature wishes to be seen …

Turning and continuing downstream, it was only a short distance to the place where the towering vertical cliffs of Gila Conglomerate reach down to join the creek And it was here, in one of those moments of instant awareness and recognition, that one encountered one of those magical special places that every seeker of Nature is always looking for but seldom finds. Such places can be sought, but cannot be summoned. Like the fragrance of a flower, such places are one of the true gifts of Nature, a gift to be experienced only in the ephemeral moment, but capable of being treasured in one’s memory forever.

The scene in itself was a simple one, just a bleached rock outcrop, reddish sediment and crystal clear creek water, with a dash of complementary plant-life green thrown in, part in shadow, part in light. But oh!, how these simple elements were arranged! In essence, it was yin and yang Nature in perfect balance: light and shadow, hard and soft, big and small, placid and turbulent, life and lifeless, and on and on. A photograph was taken. Could it capture the essence of this fleeting moment? In totality no, but in part possibly, and hopefully in a way that this gift of Nature could be shared.

Downstream from the cliffs, Bear Creek makes a sharp turn to flow west. By now the late morning light of the Solstice Sun was washing at full flood stage over the shallow waters. On the south side of the creek, and bordered by one last bedrock outcrop of Gila Conglomerate, occurs an isolated shallow pool that in times of low flow in the creek, like this day, is typically completely cut off from the main flow of the creek. Often this pool is filled with small minnows, but today it was the consummate tadpole nursery, with hundreds of black tadpoles swarming among clumps of green algae. The Monsoon rains would soon be coming with flash floods that would wash away their nursery. Would they be mature enough to survive?

The Creek is running deeper and wider downstream from the cliffs, an indication that the layer of sediment over the bedrock is thinner here than the sediment upstream from the cliffs, where more of the water in the creek is flowing through the sediment beneath the surface of the creek bed. With the increase in water depth minnows are more abundant and larger along this section of the creek, darting back and forth in small schools over the pebbled bottom, the refraction of light passing through the swirling waters altering their shapes into bizarre patterns just like the curved mirrors in the funhouse at a county fair. Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) is in full bloom along the margins of the creek, with Springwater Dancer Damselflies (Argia plana) perched on these floating masses waiting for dinner to appear, while on the adjacent stream bank thick stands of flowering White Sweet Clover (Melilotus albus) attract a variety of butterflies such as the Cabbage White (Pieris rapae), Western Honey Bees (Apis mellifera), and other small flying insects.

By 11:00 AM, the drama of the alternating play of Light and Shadow of Morning Summer Solstice is almost over. As always, the Morning Light has once again prevailed and is now penetrating into almost every corner of the Bear Creek floodplain. But not quite, for while walking back to the Casitas on the floodplain across the outwash from the Dry Wash Trail, a large group of Prickly Poppies (Argemone pleiacantha) is discovered with their back-lit blue-green leaves and delicate white blossoms with deep yellow centers glistening in high contrast against the fast-disappearing shade of a young Arizona Walnut tree.

LATE AFTERNOON LIGHT

By 6:00 PM MDT, the Summer Solstice Sun is once again beginning the eternal ever-changing competitioin of Light versus Shadow in Bear Creek Canyon. Having discovered the best vantage points for witnessing this annual contest in the past, our late afternoon journey begins at the south end of Casita lands and heads upstream in a northerly direction as the Sun slowly arcs down in the west.

Deep shadows are already encroaching on Bear Creek upon reaching the point where the morning’s observations ended seven hours ago. The light of the Afternoon Summer Solstice is markedly different than that of this morning, more yellow and warmer due to atmospheric changes. With the shadows from the Willows and Cottonwoods overarching the creek now coming in from the opposite direction, the observed landscape is immediately perceived as being very different, almost to the extent of being unrecognizable as the same location.

Walking up the Creek, this reversal in light and shadow perspective continues with cliffs now bathed in brilliant light that reflects down into the creek casting a warm glow into the deepening shadows beneath the Cottonwoods, Willows, and Seepwillows. High on the cliffs above the creek the pads of an Engelmann Prickly Pear (Opuntia engelmannii) gleam in stark silent contrast against the shadowed, eroded recesses of more weakly cemented layers of Gila Conglomerate.

Upstream from the cliffs, where the Creek channel narrows, the shadows, as witnessed in the morning, once again press in on the boulder-strewn channel, casting the creek into a near totality of deep, late afternoon darkness. Except that now it is the opposite side of the creek that is displayed in resplendent intensity as sporadic shafts of brilliant sunlight illuminate new microcosms of water, rock, and greenery along the creek, still without reason, only revealing that which Nature wishes to be seen.

Over the years, Bear Creek has migrated back and forth across the floodplain in front of the Casitas, leaving in its wake alternating linear bands of barren sediment deposits filling old creek channels and densely forested intervening stands of Willow and Cottonwood. The Floodplain Loop trail offers a unique opportunity to observe this part of the Bear Creek evolution as it follows along several of these old channels. But on this Solstice day an extra added perspective is experienced as one watches how the intervening stands of trees cast a complex, ever-changing pattern of light and shadow across the trail.

Passing from the Floodplain Loop Trail onto the Big Tree Trail, the Big Tree itself is soon encountered, the late afternoon Sun creating a kaleidoscope pattern of light and shadow on the massive multi-hundred-year-old trunk and the now deserted bistro chairs and table below. Soon after leaving the trail and heading back to the creek another of Nature’s special moments of time and space is encountered, this time a young Sycamore caught in the rays of the setting Sun, its white bark reflected in the quiet waters of the deeply shadowed creek. Magnificent!

Crossing the creek beneath the young Sycamore and climbing up onto the first terrace above the floodplain, the Big Tree trail is rejoined near the garden and the horse corral, where an extensive field of Prickly Poppies dance in the late afternoon Summer Solstice Sun. The Big Tree trail is followed north for a short distance, passing once again beneath the same overarching branches of Gooding’s Willow described in this morning’s hike, the light now coming from the opposite direction, and illuminating the first blooms of an amazing 10-foot tall stand of Common Sunflower (Helianthus annuus).

As traversed previously this morning, the Big Trail is again followed past the now shadowed curtain of tendrils of the overhanging Canyon Grape and into the darkened grove of Gray Oak. Halfway through the grove of oaks the trail is abandoned, walking west to witness a spectacular display of Summer Solstice Light and Shadow that was discovered many years ago and visited regularly on Summer Solstice ever since. Here, on the west edge of the grove stands an old oak consisting of several trunks that splay out from a common base. Beyond this oak a few other trees, including several old Junipers, grow, leaving an opening in the overhead canopy through which the late afternoon rays of the setting Summer Solstice Sun penetrate in full intensity to silhouette and cast in shadow on the ground the multiple trunks of this unique tree! Because of the unique orientations of the opening behind the oak and the oak itself, this marvelous display only occurs at Summer Solstice!

It is now nearly 7:00 PM MDT and Bear Creek Canyon is growing increasingly shadowed as the Sun sinks closer to the hills rising up just to the west of the Casitas. Climbing the Self-Guided Loop Nature Trail out of the Canyon one pauses to watch as the failing Summer Solstice Light catches the very tops of a large old Juniper, its branches loaded with a crop of soon-to-ripen berries from this Spring’s rain. And then … poof! … the Light is gone, as the Shadows of Summer Solstice prevail.