Forged by Fire • Treasured Through the Ages

Among the wide range of volcanic rocks and minerals that can be found near Casitas de Gila Guesthouses, one of the most interesting is obsidian. In geologic terms, obsidian is classified as an extrusive igneous rock or sometimes a mineraloid, but never as a mineral because it does not have a crystalline structure. Instead it is a naturally-occurring amorphous volcanic rhyolitic glass, formed when a magma or lava flow, highly rich in SiO2 cools so rapidly that crystalline minerals do not have time to form. Typically, obsidian contains between 70 and 75% SiO2, substantial amounts of magnesium oxide (MgO) and iron oxide (Fe3O4), plus numerous trace elements, such as rubidium (Rb), cesium (Cs), strontium (Sr), barium (Ba), lanthanum (La), cerium (Ce), yttrium (Y), titanium (Ti), zirconium (Zr), phosporous (P), tantalum (Ta) or niobium (Nb).

Obsidian is easily identified by its glassy, conchoidal fracture and its brown or smoky-gray to black color. Sometimes it may contain inclusions of small, white crystals of the mineral cristobalite, a high-temperature form of SiO2, or it may contain linear or swirling patterns of extremely small gas bubbles retained within the flowing magma or lava before it was rapidly cooled.

Obsidian is found around the world wherever rhyolitic magma (containing 70% or more SiO2 and less than 2% water) occur. In the United States, obsidian occurs in most western states and is abundant within western New Mexico and Arizona. Similar deposits of obsidian occur just south of the border in the Mexican States of Sonora and Chihuahua.

Obsidian is not stable at the earth’s surface and consequently is rarely found in rocks more than a few tens of millions of years old. The reason for this is that over time, ever so slowly, obsidian absorbs water into its structure, and once that happens the obsidian converts to another natural glass or mineraloid called perlite. Thus, many volcanic deposits that originally formed as obsidian are now entirely converted to perlite. Not all perlite deposits form from hydration of obsidian, however. If a rapidly cooled, rhyolitic magma contains 2% or more water to start with, then the resultant volcanic glass will solidify as perlite, not obsidian.

THE MULE CREEK REGION OBSIDIAN DEPOSITS

The geologic history of western New Mexico during the Late Paleogene to Early Neogene Periods (old terminology Mid to Late Tertiary) was basically a time of extensive and ongoing volcanic activity. By the end of Oligocene Epoch the lengthy period of massive eruptions of the Super-volcanoes within the Gila Wilderness (35-28 million years ago) had come to an end, and the focus for most of the ensuing volcanic activity within the Grant County/Catron County, NM, border area over the next 10 million years or so during the Miocene Epoch shifted westward towards the Arizona/New Mexico border and into eastern Arizona. It was during this time between 20 and 17 million years ago that the obsidian deposits of the Mule Creek region were formed.

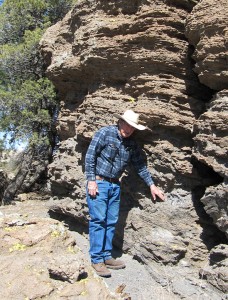

Extensive research by M. Steven Shackley, Department of Anthropology at the University of California at Berkley, regarding archaeological sources and use of obsidian in the American Southwest indicates that the Mule Creek Obsidian Deposits are probably the most extensive occurrence geographically of obsidian anywhere in the Southwest. The deposits are located about 20 miles northwest of the Casitas and occur within a greater than 100 square mile area that centers around the small community of Mule Creek, New Mexico, about five miles from the Arizona border. Within this vast area that includes portions of Grant and Catron Counties in New Mexico and Greenlee County in Arizona, are numerous, extensive obsidian-bearing volcanic rhyolitic ash flow deposits. When found in place, the obsidian occurs as small nodules, generally two inches (5cm) or less in diameter, but occasionally up to twice that size, within outcrops of perlitic ash-flow deposits that absolute dating shows were ejected 17.7 million years ago.

The scientific name for these obsidian nodules is marekanites which take their name from the Marekanka River in the Okhotsk basin in Siberia, Russia, where they were described over a hundred years ago. A more recent, common name that is often given to these obsidian nodules is that of “Apache tears”, a name coined by mineral collectors, rockhounds and lapidary enthusiasts for the obsidian nodules found in the American Southwest. In addition to the widely distributed outcrops of marekanite bearing perlite deposits of the Mule Creek Obsidian Deposits, the obsidian nodules also occur as a significant constituent of virtually all Quaternary Period alluvium deposits which have been eroded from the bedrock outcrops and redeposited in stream beds and valleys throughout the region.

TREASURED THROUGHOUT THE AGES

Obsidian has been a treasured natural resource of prehistoric and historic cultures worldwide since the beginning of the Stone Age because of its glassy composition and conchoidal fracture, allowing the rock to be easily worked into extremely sharp projectile points, cutting blades and other tools. Because of its limited occurrence, good sources were highly sought after by prehistoric cultures, most likely fought over, and became the basis of early production centers, commerce, and trade routes.

Archaeological research of the late pre-historic cultures of the American Southwest and Northern Mexico conducted by Dr. Shackley at the University of California at Berkley and research done as part of the Preservation Fellowship Program at the private non-profit organization Archaeology Southwest has shown that the Mule Creek Obsidian Deposits were extensively mined and utilized by early cultures, and that the raw obsidian nodules and probably partially finished products (called blanks) were widely utilized and traded within in New Mexico and Southern Arizona. The evidence for this is based on analyzing the trace element composition of obsidian artifacts, and then comparing the results with the trace element composition of known obsidian source deposits.

Extensive analysis of numerous obsidian source areas has shown that the type, amounts of, and the ratios of various trace elements within a source area are essentially unique, and thus can be used as a diagnostic tool for determining the source of the material used in an artifact’s manufacture, as well as providing clues as to distribution patterns and possible trade routes for the raw material.

Today obsidian is still used in the manufacture of precision cutting tools such as scalpels used in surgery. The reason for this is that a fractured edge of obsidian is far sharper than any surgical steel blade manufactured. Research on the effectiveness of obsidian scalpels has shown that wounds heal faster, with less scarring, and without complications.

The use of obsidian in jewelry, stone carvings, and sculptures goes back for thousands of years and continues today, where it finds abundant use in inexpensive, mass-produced jewelry, as well as high-end artisan jewelry, and as a carving stone for sculptures.

MULE CREEK OBSIDIAN AT THE HIGHWAY’S EDGE

For travelers who delight in taking the road less travelled, the most scenic route between the southern Arizona cities of Tucson and Phoenix and Casitas de Gila Guesthouses involves a spectacular one-hour drive through the Apache National Forest in Arizona and the Gila National Forest in New Mexico over AZ/NM Highway 78. About five miles east of the Arizona/New Mexico border, NM 78 passes through the small community of Mule Creek, which has a US Post Office (at least at the time of this writing), but no other stores. Near the sign for the post office there is a dip in the road where the typically dry Mule Creek crosses the road. For the traveller in a hurry, a one-minute stop here at the side of the road will almost always produce a couple of nice Marekanites left behind by short-term flooding of Mule Creek during periods of high runoff from the surrounding hills. For the more serious rockhound or geology afflicted souls, rest assured that longer visits into the surrounding Gila National Forest in this area can provide anywhere from a day to a lifetime of memorable geological experiences!