Sitting in front of Casitas de Gila Guesthouses, one is presented with an overwhelming panorama of pristine natural beauty stretching from the distant mountainous ramparts of the Gila Wilderness to the close-up verdant oasis of the Bear Creek drainage in the canyon below. The scene is ever changing with the seasons, offering unlimited photographic opportunities for both novice and professional alike. Hiking the numerous trails at the Casitas offers a closer and more intimate photographic exploration into Nature, from shear, vertical cliffs of Gila Conglomerate towering over gnarled, ancient, and massive sycamores and cottonwoods to the challenging pursuit of the diverse birds and animals that inhabit the Casita Nature Preserve. Yet, while these photo opportunities are exceptional and can provide hours of enjoyment at the Casitas, there is another natural world awaiting, hardly noticed and even more rarely travelled: The Colorful World of the Lichens of the Gila.

Lichens are some of most bizarre and interesting organisms found on our planet. They thrive in all climates and geographic zones of the Earth, from barren frozen polar regions, to the lowest, hottest deserts, to the highest rocky mountain peaks, to the edge of the ocean, to temperate and tropical forests. However, for the greater part of humanity, they are little understood. So to begin, exactly what are Lichens?

First of all, lichens are not individual species of organisms at all. Rather, they are a composite life form consisting of two, and sometimes even three, completely different species which live in a symbiotic, mutually-beneficial relationship. The greatest number of lichens species consist of a species of fungus, which is used for the scientific name of the lichen, and a species of plant called green algae. In some lichens, a species of photosynthesizing bacterium, called a cyanobacterium, takes the place of the green algal species. And in some lichens, all three species of organisms are present. The fungal component is dominant and makes up the main body of a lichen. It consists of a dense matrix of filaments completely enclosing, and thus benefitting, the photosyntheisizing algal or cyanobacterium components by shading them from intense sunlight and preventing them from drying out. In turn, the chlorophyll bearing algal and cyanobacterial components are able to use the sunlight’s energy to produce and provide food and nutrients for the fungal component through the photosynthetic conversion of water and carbon dioxide.

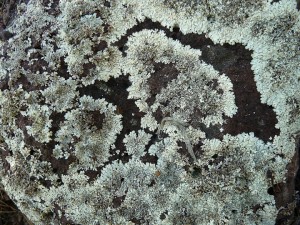

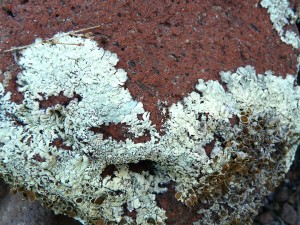

The main body of the lichen, called the thallus, can be classified on the basis of growth form into several categories: crustose (flat, paint-like coatings), foliose (leaf-like), fruticose (branched, miniature shrub-like), leprose (powdery), filamentous (hair-like), or gelatinous. Of these, it is the crustose and foliose lichens found on the various loose surface rocks and exposed bedrock that are most likely to catch the eye of the visitor to the high desert Gila area of the American Southwest here at the Casitas.

Lichens are very slow growing, spreading laterally outward from their point of inception in most species at rates typically ranging from 0.1 to 1.5 mm per year. Growth rates within certain species, particularly the crustose species, tends to be very constant through time. Consequently, the scientific discipline of lichenometry (age determination of exposed rock surfaces by lichen measurement) has become an important tool in archeology and geology and related disciplines. By measuring the diameter of the largest lichens, scientists can determine dates of specific events, such as at sites of human habitation, or in determining cycles of climate change by examining moraine deposits (rock debris) left by the retreat of melting alpine glaciers. Growth rates for various species can be easily determined by measuring lichens on dated tombstones or old buildings. In more recent years, C14 dating using AMS (accelerator mass spectroscopy) has proven very successful in lichen dating, providing corroborating data for rates of growth determined by direct measurement methods. Lichenometry is most accurate on surfaces exposed for less than a 1,000 years; however, it can be used on ancient rock surfaces up to about 10,000 years. Here at the Casitas, one can observe crustose lichens on boulders and bedrock surfaces that are hundreds of years old.

Lichens have been utilized by humans for thousands of years in diverse ways, including:

- Food – For most human cultures lichens have served primarily as a famine food, particularly for peoples living in the northern latitudes. However, in some cultures lichens are considered a staple, even a delicacy. Very few lichens are poisonous, but most contain poorly digested compounds which can be removed by simple processes, such as boiling. Human use as a food in North America’s Southwest was apparently never significant.

For wild and domesticated animals a few lichens serve as both forage and fodder, primarily in extreme environments of the far north and in lower latitude desert areas. In New Mexico lichen has been reported as a forage for antelope. - Natural Dye – Lichens have long been used as a natural dye for yarn, textiles and basketry. The dye is extracted by boiling or steeping in ammonia or urine. Common colors are shades of yellow and tan, however, a few species produce reds and purples. Here in New Mexico lichens have a strong tradition of use in woolen rugs and blankets woven by the Navajo, and in basketry by other tribes in the Southwest.

- Medicine – Lichens have been and are still used medicinally by numerous cultures around the globe. Their primary use stems from a variety of secondary compounds found in the fungal component of the thallus which can be used as an antibiotic for a wide variety of ailments, both internal and external. Here in New Mexico lichens have a long history of medicinal use by both Native American and Hispanic cultures.

- Other Uses – Lichens have a long history of use in numerous and highly diverse ways around the globe, including cosmetics, perfumes, fibers, poisons, hallucinogens, preservatives and hide tanning!

THE ROCK-COVERING LICHENS

OF THE CASITAS DE GILA NATURE PRESERVE

As one explores the various hiking trails at Casitas de Gila, it will be noticed that the type and abundance of lichens found growing on the rocks observed along the way vary considerably, both in species type, form, size and color. Major controls for this variation include:

- Rock Composition – Even a cursory study of the type of lichens covering the various rock surfaces at the Casitas will show that specific types of lichens seem to show a preference for specific types of rocks. This is due not only to the composition of the rock but also to the degree and ease to which a specific rock type is broken down by mechanical and chemical weathering to provide nutrients to the algal component of the lichen.

Almost all of the rocks found around the Casitas are volcanic in origin. Compositionally, they consist primarily of light-colored rhyolite and andesite, plus a much smaller amount of dark-colored basalt, which formed as lava and pyroclastic flows and welded tuffs. Across Bear Creek from the Casitas these volcanic rocks are well exposed in outcrops found on the mountain side along the Paradise Overlook Trail. Closer to the Casitas, the cliffs on both sides of Bear Creek consist primarily of rounded pebble-size to boulder-size pieces of similar volcanic material that was carried down from the surrounding volcanic mountains by rivers and streams to be subsequently deposited as the Gila Conglomerate some 6 to 10 million years ago. Over hundreds of thousands of years, the upper surfaces of the weakly consolidated and cemented Gila Conglomerate were broken down through mechanical and chemical weathering to release the abundant small pebbles to large boulders found on the flats around the Casitas on which lichens subsequently became established. - Surface Reflectivity of the Rock Substrate – The surface reflectivity of rocks is a function of both rock composition and surface texture. Light-colored rocks and a smooth surface texture will reflect the Sun’s rays and heat, while dark-colored rocks and a rough surface will absorb the Sun’s rays and heat up. The degree of surface reflectivity also has an effect on the length of time moisture is retained on or within the rock surface, which of course is an important factor for lichen growth.

- Directional Orientation of the Rock Surface – The orientation of a rock’s surface relative to compass directions and inclination from the horizontal greatly influences lichen growth by determining the amount and angle at which the Sun’s rays strike the rock surface. These factors in turn influence the temperature and moisture retention of the rock substrate.

- Amount of Daily and Seasonal Sunlight vs. Shade over the Rock Surface – Location of a rock surface relative to shade-producing features such as trees, and adjacent topographic features such a canyon walls or cliffs, can greatly affect and control lichen development and growth rates by regulating the amount of sunlight received and the time of year that it is received.

- Amount of Rainfall Received and moisture retention potential of the rock surface and surrounding ground surface – Water is essential for lichen growth and survival and the amount of rainfall received on the rock surface annually and seasonally can be further affected by the orientation of the surface and how rapidly rainwater drains from the surface. Moisture retention at and within the rock surface is also a factor since some rocks are somewhat permeable and can soak up and retain water like a sponge or have thin accumulations of soil which will retain water.

- Stability of the Rock Surface Itself – The old adage “a rolling stone gathers no moss” applies to lichens as well. While some outcrops of bedrock can be stable for thousands of years, favoring the growth of ancient lichens, other outcrops can erode so quickly through mechanical and chemical weathering that lichens cannot establish on them. For loose rocks and boulders, the degree of slope of the surface on which they rest is critical since gravity, animal activity, and soil erosion and deposition can move or cover up loose rocks prohibiting lichen growth. Indeed, by walking the trails around the Casitas one can observe and determine soil surfaces of all degrees of stability simply by noting the presence and size of the lichens.

All of the photographs presented in this blog were taken within a few hundred feet of the Casitas’ guesthouses. A wide variety of species can be found which exhibit a gamut of colors from brilliant yellows and reds to steel-blue grays and drab browns. Their textures range from simple pain-like encrustations to bizarre leafy forms displaying incredibly detailed fractal patterns. If you have a camera with even minimal macro-photographic capability, you will find that a whole new world of Nature’s color, texture, and design awaits you at Casitas de Gila!