Many Questions, A Few Clues, Emerging Answers

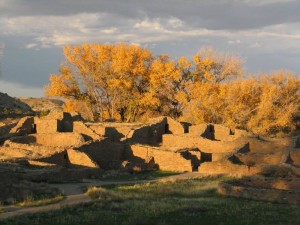

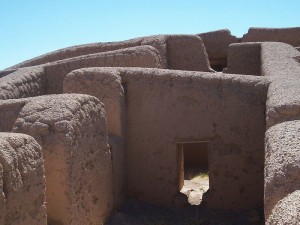

The Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, located 45 miles north of Silver City in the middle of the Gila Wilderness, is a unique cultural site in Southern New Mexico. Yet, despite 131 years of study and research since the great anthropologist Adolph Bandelier visited the Cliff Dwellings and the nearby TJ Ruins in 1884, and the subsequent discovery of many important clues as to its origin and abandonment, the site is still little understood, its mystery securely wrapped in the silent stones.

Part 1 of this Blog presents many of the significant facts and data surrounding the Cliff Dwellings and TJ Ruins that have been discovered over the years, along with key questions that the data raise, plus some partial answers and a few speculations. As previously noted in Part 1, it is unlikely that significantly more data will be recovered from the Cliff Dwellings as they are at this time almost completely excavated at the professional level, with much critical information forever lost to looting and vandalism in the years prior to the establishment of the Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. The TJ Ruins, however, remain essentially untouched and un-excavated. Whenever the TJ Ruins are excavated, it is considered quite likely to this writer that more answers will be forthcoming to the questions raised in Part 1 of this Blog regarding the Cliff Dwellings, which are repeated below:

- Who were these Cliff Dwellers anyway and what were they like?

- Where did they come from?

- Why did they come, and why did they choose to stay in dark, cold caves as opposed to the large TJ Ruin?

- Were there people living in at the TJ Ruin site at the time, and if so what was their relationship with the Cliff Dwellers?

- Why did they stay such a short time? (as suggested by lack of adult burials, lack of trash, lack of building modifications and additions), and Why did they leave?

- Where did they go?

Until the excavation of the TJ Ruins takes place, there is little more that can be learned directly from the Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument itself. There is, however, a vast wealth of existing regional Southwest archaeological data and information for what was happening in the Northwest New Mexico portion of the Four Corners Area involving the Anasazi, Chaco and Aztec Cultures from the 10th to the late 13th Century. This data and information, when considered in context with the Gila Cliff Dwellings, offers tantalizing clues and possible answers to the above questions.

Part 2 of this Blog begins with a brief summary of the Rise and Fall of the Anasazi Chaco and Aztec Culture, and uses it to develop a speculative scenario as to the possible origin and abandonment of this mysterious, isolated cultural site of the Gila Cliff Dwellings in Southern New Mexico.

THE RISE AND FALL OF THE ANASAZI (ANCESTRAL PUEBLO) CULTURE

AT CHACO AND AZTEC

Note: Unless otherwise indicated, most of the facts, data, and information reported in this section

are derived from Lekson, S.A., 2015, The Chaco Meridian1

First Came Chaco . . .

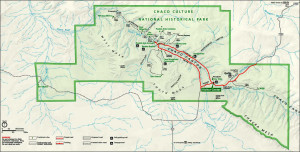

Between 850 and 1275 AD, the Four Corners area of the United States (Utah/Colorado/New Mexico/Arizona) witnessed the development of the largest and most advanced Native American culture in the Southwest. This was the Anasazi or Ancestral Pueblo Culture which at its peak between the late 11th and early 12th centuries grew to a population that Lekson believes was “something under 100,000 people”, spreading out as much as 250 kilometers (155 miles) from its geographic, cultural, and political center at Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon. Pueblo Bonito is just one of 12 major Anasazi Pueblo Ruins in the Chaco Culture National Historical Park, which is located in the northwest corner of New Mexico about 100 miles northwest of Albuquerque.

The numerous Pueblo ruins in Chaco Canyon and the surrounding area have been the focus of extensive and still-ongoing formal archaeological research since 1896. In 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt set aside a portion of Chaco Canyon as a National Monument. Additional lands were added over the years. In December 1980, the small National Monument became the Chaco Culture National Historical Park to protect the more than 2,400 archaeological sites within the Park’s boundaries.

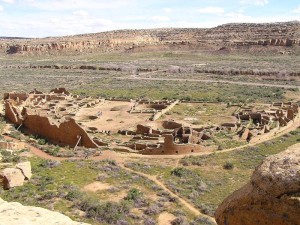

After more than a hundred years of archaeological investigations, it is clear that the so-called “Chaco Phenomenon”, a term coined by archaeologist Cynthia Irwin-Williams in 1972, was indeed just that. What took place there was unique in Southwest U.S. archaeology in every sense of the word: from its magnificent and massive 4- to 5-story exquisite stone buildings known as Great Houses, and huge, above and below ground circular-shaped Great Kivas adjoining large adjacent open plazas, to the nearby scattering of small, one-story, single-family Unit Pueblos with a small kiva, to an extensive road system leading to many of the 150 identified surrounding smaller “Outlier” villages as much as a 100 miles or more away, each with their own Great House and Great Kiva and surrounding smaller Unit Pueblos. Indeed, there was nothing like it either before or after what has been collectively referred to as the Chaco World or the Chaco System.

In the past two decades, somewhat of a consensus has been emerging regarding a basic understanding of the architecture, social, religious, economic, and political components of the Chaco World. Key aspects of this understanding that are considered important relative to answering the questions posed above regarding the Gila Cliff Dwellings are given below.

ARCHITECTURE

In Chaco, named for its location in Chaco Canyon, architecture was of two main types: 1) massive and magnificent Great Houses soaring up to 5 stories high, built of finely worked, thick stone masonry with unique T-shaped doors for all to see, with adjacent, equally large and impressive Great Kivas, bordering large open plazas; and 2) nearby scattered single family, small, 5 or 6 room Unit Pueblos of rough stone masonry and mud, commonly with an adjacent small kiva.

Architecture in the Outlier villages was very similar to that of the major Chaco sites located in Chaco Wash except on a smaller scale: a Great House and Great Kiva with nearby scattered single-family Unit Pueblos.

SOCIAL

Chaco culture was stratified, with a very distinct class structure. Chaco was not an egalitarian commune, as was thought by many early on. There were Nobles, Elites, or Lords who lived in the Great Houses and did important things and thinking in the Great Houses; and then there were the Commoners, peons or serfs who lived in the small unit pueblos and labored to build the great buildings and roads, to serve the Nobles, and to toil endlessly in the fields to produce the food for the Chaco system.

The Nobles did no manual labor, nor did they build the Great Houses. The lack of hearths in the Great Houses suggests they didn’t do their own cooking either; food was probably prepared for them by servants or slaves in the plazas where large cooking pits have been excavated.

It was easy to tell the Nobles: they wore exotic jewelry of marine shells and Scarlet Macaw feathers – lots of feathers – and copper bells imported from Mexico, plus turquoise jewelry from Chacoan mines near Outlier villages to the east. And while they sat in the splendor of their Great Houses, talking to their Scarlet Macaws, they drank Cacao (chocolate), also imported from Mexico, from unique and exclusively-Noble cylinder-shaped pottery mugs. and laid plans for their next building or road project. Another important annual decision involved deciding which of the outlier villages that did not get enough rain for their crops that year, but had remained faithful to the Chacoan Code of Rules, deserved to be issued grain from the Chaco Great House storage bins.

The commoners, on the other hand, were typical of all commoners throughout history: born to a lifetime of work from dawn to dark, or born to serve, and if they worked and served well, and above all obeyed the Nobles’ rules, possibly they, too, could acquire a bauble of marine shell or a piece of turquoise, but, except for the extremely good, probably not a macaw feather.

RELIGIOUS

Christy Turner2 in his 1999 book Man Corn, Cannibalism and Violence in the Prehistoric American Southwest writes extensively about archaeological and ethnographic evidence that the Chaco World and other Southwestern Native American cultures “received, imported, adopted or adapted elements of Mexican Indian religion or cosmology”. This evidence is seen in rock art (petroglyphs and pictographs), scenes on Mimbres pottery, paintings on kiva walls, and religious paraphernalia and practices, especially those that bear resemblance to two ancient Mesoamerican deities, Quetzalcoatl, the Feathered Serpent and Xipe Totec, “Our Lord the Flayed One”, both of which are associated with ritual sacrifice.

ECONOMIC

Most archaeologists in working on the nature of Chacoan and other prehistoric Southwestern economies have focused on localized subsistence economies, those based on food (maize, squash, and beans), pottery, rocks (obsidian for projectile points) or human labor. Exotic objects found in Chacoan ruins, such as Scarlet Macaw feathers and skeletal material, marine sea shell jewelry, copper bells, and turquoise, generally received little attention or mention, being considered nothing more than trinkets for “would-be Elites”.

There was a subsistence economy in the Chacoan World, an economy that basically functioned within a 150 km (90 miles) radius of the Chaco Center in Chaco Canyon, where Chaco served as central warehouse and redistribution center to outlier villages, which functioned, perhaps, in some form of a “from each according to their ability, to each according to their need”, or maybe “render unto Caeser the things that are Caeser’s … or else” basis.

There was also, however, what Lekson (2015) calls a “political-prestige economy” which was based on exotic materials and objects such as macaw birds and feathers, marine shell objects, copper bells, jet frogs, cacao, and turquoise. Most of these materials and objects were wearable or easily portable symbols of nobility, office, rank, wealth, and most importantly, Power. This prestige economy could be used in establishing alliances, and extending the Chacoan policy outward to great distances, distances as much as 250 km (150 miles), which lay far beyond the practicalities and logistics of subsistence economies.

POLITICAL

While many earlier archaeologists spoke in their own terms of a political hierarchical/class structured society at Chaco, it was not until Lekson (2015) was introduced to the concept of the Postclassic Mesoamerican Altepetl that he felt he had found a political/social/governing system that closely fit the diverse data gathered from over a hundred years of research and excavation of Chaco. As Lekson describes: the altepetl (plural altepeme) consisted of a ruling class of several (6 or 8) ruling families and their associated commoners within a defined agricultural territory. There could be a hierarchy of altepemes with Major Nobles and their Commoners and Secondary Nobles with their Commoners. In this system the Commoners were obligated to contribute a certain amount of goods (crop harvest for example) or labor (building the Great Houses were the Nobles resided) to their Noble families. Major Nobles would live in a larger, centralized or “urban” altepetl such as the magnificent Great House centers of Chaco Canyon, while their Commoners lived in nearby Unit Pueblos. Secondary Nobles would rule over smaller altepemes in the surrounding countryside, the so-called Chaco “Outliers”, living in smaller Great Houses, which would be surrounded by a number of Unit Pueblos where the Commoners lived. In this system, just as Commoners paid tribute in goods or labor to their Noble families, Secondary Nobles were obligated to pay tribute in goods or services to the Major Nobles. While there was a Chief Noble or King, the kingship did not pass down by blood heritage when replacement was needed, but rather the successor was decided upon by the half dozen or so Major Noble families, and generally not chosen from the outgoing Noble family.

Then Came Aztec . . .

Chaco began somewhere around 850 AD and experienced a golden age period of infrastructure and population growth between 1020 and 1125, when construction of buildings ceased. Around 1080 something triggered a decision to move the capital from Chaco Canyon to some 90 km (54 miles) north to what is now known as Aztec Ruins National Momument on the Animas River. The Aztec Ruins are in many ways very similar in architecture and layout to Chaco Ruins with Great Houses, Great Kivas, surrounding complexes of unit Pueblos, as well as some new building designs of circular tri-walled structures. Construction began at Aztec around 1100, about the same time as the building of the Great North Road commenced that would connect Chaco to Aztec, and by 1125, the new capital or center was essentially completed. Aztec functioned as the central seat of power in the Chacoan World until 1275, when a final collapse and abandonment of the Chacoan World took place.

THE COLLAPSE AND ABANDONMENT OF THE CHACOAN WORLD

As stated in Part 1 of this blog, the last part of the 150 year time period, between 1150 and 1300 has long been considered a time period critical to the understanding of two of the greatest mysteries in the archaeology of the Southwest. These mysteries, sometimes referred to as The Great Collapse or The Great Abandonment, concern the time period when two of the three largest and most evolved Southwestern Native American Cultures, the Mogollon and the Ancestral Pueblo (Anasazi), experienced major change and societal upheaval. This upheaval was both widespread, long-term, and chronic throughout their domains, ultimately resulting in the eventual collapse of these two advanced cultures’ social structure, and the subsequent abandonment of their villages and larger population centers. The cause (or causes) of this collapse and abandonment has been the subject of strong and often vitriolic ongoing debate for decades.

Early on in the research of the Chocoan World, archaeologists began to consider chronic drought with accompanying starvation as the primary cause for the collapse and abandonment. In recent years other possible causes have been proposed, such as introduction of new religious beliefs, depletion of resources such as deforestation and subsequent erosion of agricultural lands, and possible warfare or rebellion.

The following sections will discuss several lines of recent research which, when combined, offer strong evidence for a proposed climatic root cause and a resulting political/societal upheaval scenario that led to the collapse and abandonment of the Chaco World. Following that, the proposed scenario will be used to suggest further answers to the key questions raised in Part 1 of this blog about the Gila Cliff Dwellings. We begin with a close look at climate data for the past 2,000 years in New Mexico.

2,000 YEARS OF CLIMATE CHANGE IN NEW MEXICO

For several years now, as any follower of contemporary news has noticed, there has been a lot of concern over Climate Change and what it means to current civilization. For any student of earth history, Climate Change is nothing new. The Earth’s Climate (as well as its geology, geography, and resident life) has always been in a state of dynamic change, and it always will be. In this section we will take a quick look at the last 2,000 years of Climate Change in New Mexico and its affect upon its prehistoric cultures.

Climate, as defined by Merriam-Webster, and as used here, refers to “the average course or condition of the weather at a place usually over a period of years as exhibited by temperature, wind velocity, and precipitation.” Paleoclimatology is the study of climate change in prehistoric times. Measurement of temperature, and precipitation in the prehistoric past can be determined by a variety of climate proxies. Proxies for ancient wind patterns also exist, but are much less precise; for example, study of a down-wind deposit of volcanic ash from a known or suspected volcanic eruption.

TEMPERATURE TRENDS IN NORTHERN NEW MEXICO, 800 TO 1300 AD

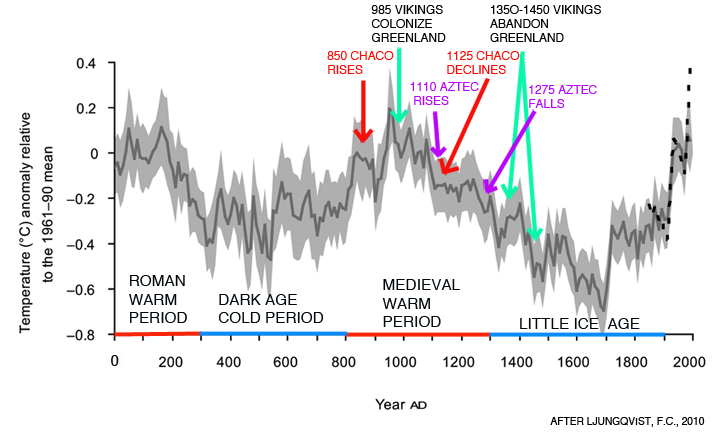

Figure 1 below is a graph from F.C. Ljungqvist’s 20103 reconstruction of global temperature for the last 2000 years in the Northern Hemisphere. The study is based on 30 temperature sensitive proxies, including: historical documents, marine sediment records, lake sediment records, ice core oxygen isotope records, varved sediment records, and tree ring records globally distributed around the Northern Hemisphere between 30° and 90°N.

Ljungqvist’s research has yielded substantial evidence that the changes in global temperature shown by the graph in Figure 1 during the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age were experienced throughout all portions of the Northern Hemisphere. Figure1 illustrates how these periods of major climate change can be used to better understand major human cultural endeavors in the historic past. Superimposed on Ljungqvist’s graph are historically documented dates for the Viking colonization and later abandonment of Greenland as recorded in the ancient Viking Sagas, as well as in Icelandic writings at that time. As shown in the graph, and confirmed by the historical records and modern archaeological excavations, we can see how climate controlled the Viking colonization and prosperity during the Medieval Warm Period and subsequent abandonment during the ensuing Little Ice Age.

Also shown on the graph are the dates given by Lekson (2015) for the rise and decline of Chaco and the rise and fall of Aztec. It can be seen that the rise of Chaco around 850 and its subsequent golden age coincided with the warmest part of the Medieval Warm Period, and that the climate entered a substantial cooling period around 1080 a few years before construction stopped at Chaco in 1125. The moving of the Chacoan capital from Chaco Canyon to Aztec began during this time period with construction beginning at Aztec around 1110. The building of Aztec took place rapidly so that by 1125 Aztec was flourishing while Chaco was beginning its decline. From 1100 temperature remained fairly stable globally until about 1250 when cooling increased, gradually bringing the Medieval Warm Period to an end and ushering in the Little Ice Age at 1300. During this period Aztec falls around 1275, bringing to an end the Chaco Phenomenon in the Four Corners area.

Fig. 1: Graph of Global extra-tropical Northern hemisphere (30-90°) decadal mean temperature variations (dark grey line), with 2 standard deviation error bars (light grey shading) after Ljungqvist, 2010. Time periods shown for the Roman Warm Period, Dark Age Cold Period, Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age are Ljungqvist’s. Anasazi Chaco and Aztec Culture dates are from Lekson, 2015; Vikings dates are from D’Andrea and Huang, 2011.

RAINFALL TRENDS IN NORTHERN NEW MEXICO, 0-1650 AD

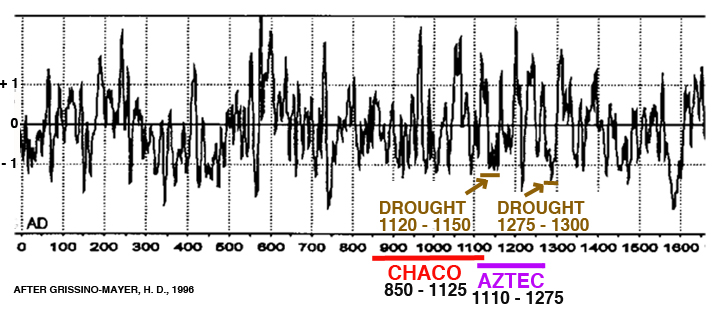

When considering the paleoclimate for any area, temperature, of course, is only part of the equation, the other major determinant being precipitation. Fortunately, a very detailed record for precipitation at the time of the Chaco Phenomenon is available for Northern New Mexico from the field of dendroclimatology. Dendroclimatology is the scientific method that uses measurements and patterns of tree rings (also known as growth rings) as a proxy to reconstruct past climate. In 1996, an in-depth research study based on tree ring analysis was published which details past precipitation for the El Malpais National Monument Volcanic Field in Central New Mexico for the last 2,200 years. The Malpais is located only 80 miles south of Chaco Canyon.

Figure 2 below is a graph showing above and below average precipitation for the Malpais National Monument volcanic field lava flow area in New Mexico between 0 and 1650. This graph is based on H.D. Grissino-Mayer’s 1996 in-depth study4 of tree-ring width analyses from 248 measurement series of cores obtained from living trees and sub-fossil wood (dead, down and not decayed) from long-lived Douglas Fir and Ponderosa Pine found in the Malpais. Because of the unique hydrologic conditions in the Malpais lava flow fields, trees growing on the lava flow over the past 2,000 years exhibit a very accurate dendrochronologic record of variations in annual precipitation patterns.

Fig. 2: This graph of annual rainfall in Malpais region New Mexico. Curve is a 10-year smoothed curve of yearly tree-ring width fit to accentuate short-term (less than 50 yr) climate episodes. Horizontal 0 line separates above normal precipitation (Positive standard deviation) from below normal precipitation (Negative standard deviation). After Grissino-Mayer, H.D., 1996. Rise and fall dates of the Anasazi Chaco and Aztec Cultures and drought dates are from Lekson, 2015.

Periods of cyclical drought are an inherent and a defining characteristic of the American Southwest from prehistoric times to the modern present, and can be expected into the foreseeable future. Every culture who has lived there, from the prehistoric past right up to the present, has experienced droughts and dealt with them, with various degrees of success, depending on the particular time period in which they lived there. The ecological concept of Adapt or Perish is particularly appropriate for any culture that has ever tried to live in the American Southwest. In the next section we will focus on how drought or the lack thereof influenced the rise and fall of the Chacoan Phenomenon. But first, a few comments about Figure 2.

Archaeological research on the Chacoan Phenomenon has identified various time periods of drought, some long, some short, some local, some widespread. In looking at the graph in Figure 2 its obvious that fluctuations in precipitation in Northern New Mexico seem to be the rule rather than the exception. However, there have been two periods of drought that most researchers tend to agree on as being significant during the time periods of Chaco and Aztec – the first being an extended period of drought between 1120 and 1150 (some research suggests 1180), and a second major drought period between 1275 and 1300. In comparing these droughts with the rise, decline, and fall dates of Chaco and Aztec, it must be kept in mind that the graph is showing total annual precipitation in which both winter and summer rainfall are combined. Variations in seasonal rainfall (summer vs winter) cannot be determined. This is a critical point in considering the impact of climate change upon the Chacoan Phenomenon because the success or failure of farming and harvests at that time was completely dependent upon the Summer Southwest Monsoon rains, which can be notoriously variable from year to year, both in terms of time and location. How major changes in climate might have affected the Monsoon rains is little known.

WAS DROUGHT IN THE MEDIEVAL WARM PERIOD AND THE LITTLE ICE AGE THE ROOT CAUSE THAT LED TO THE COLLAPSE AND ABANDONMENT OF THE CHACOAN WORLD?

This section discusses this writer’s speculative proposition that the two periods of drought shown in Figure 2 could indeed have been the root cause or catalyst that triggered the ultimate collapse and abandonment of the Chacoan World. Central to this proposition is Lekson’s 2015 proposal that the Chacoan political/social/government system as discussed above was essentially a modified version of the Mesoamerican Altepetl System consisting of Noble rulers living in Great Houses governing commoner farmers and labors, who paid tribute or taxes through goods (such as a portion of yearly harvest) or labor.

The Altepetl System as developed in Mesoamerica worked well there for hundreds of years from the Post Classic Period on (900-1519), and with some possible local adaptation by the Chaco Nobles, would have worked well during the height of the Medieval Warm Period at Chaco during the boom years of construction, expansion, and population growth when the climate was warm and precipitation plentiful. Then beginning around 1120 a series of droughts ensued during a period of climate instability for 30-60 years during which summer rains and other weather factors became increasingly unreliable as the global climate began to cool. Dry farming on the mesa tops, which had become possible at the height of the Medieval Warm Period, now became untenable, and the summer monsoon rains, which are always highly variable from year to year in terms of how much rain any specific area will receive, became even less dependable. The Major Nobles now had a problem, one that was not going to go away …

The problem was that their far flung 150-member atlepetl system had been constructed around the concept that in any given year, enough of the individual Outlier Great House altepetls would get enough rain for a successful harvest so that overall, the Total Choacan Summer Harvest would have a sufficient surplus to feed everyone in the Chaco System within the 150 kilometer (90 mile) radius of Great House Outliers, which operated on the Chaco Subsistence Economy. Those Outlier Altepetls that had not received rain from the increasingly less dependable Summer Monsoon did not have to worry, but could remain secure in the understanding that not only would they be fed that winter from the Food Bank Surplus in Chaco Center, but, if necessary, they would also be provided with seeds for the coming year’s planting!

But then, as the droughts increased in frequency and severity, came the years when the critical threshold was reached where the number of Great House Outliers with harvest failures exceeded the number of successful Outlier harvests, and the Food Bank Surplus in Chaco Center could not meet the Overall Demand. The Chaco System and the all knowing, all powerful and heretofore benevolent Nobles’ credibility was failing. What could the Nobles possibly do?

The rest of this speculative scenario is not hard to envision. What is known from the archaeological record as Lekson (2015) relates, and Turner and Turner (1999), and Kohler, et al. (2014)5 document is that during Chaco’s time, and especially in the later decades of the interval between 1020 and 1180, there were instances in the Chaco World of extreme violence ranging from individual killings or sacrifice to massacres of whole communities – from infants to the aged – being executed, dismembered, and in some cases even eaten, their bones then tossed into an empty room or kiva. Was this violence done under orders or direction of the Nobles, or was it just intra-Outlier hunger-driven, mob-violence warfare? A review of the nature of the religious component of the Chaco Culture as discussed above would suggest the former, especially when one considers that 6 out of the 76 sites studied by Turner and Turner were in Chaco Center in Chaco Canyon that included both extreme violence and cannibalism, some of which was found within the Great Houses.

It is conceivable that when the suggested Noble-instigated and directed sacrifice, intimidation by dismemberment, and even worse, failed to increase crop production among the farming Commoners, and whole Outlier villages were abandoned as Commoners fled en masse during the night, in terror, to the East, West, and South, that the Major Nobles at Chaco Center may have seen the need for a new course of action. Eventually they may have come to the conclusion that maybe the failing harvests were the result of the climate after all, and not the fault of lazy, incompetent Commoner farmers, and that they should move Chaco Center to Aztec where the year-around waters of the Animas River could be used to irrigate and ensure dependable harvests. Which they did around 1110.

After the move to Aztec, as Lekson (2015) relates, apparently things were more peaceful between 1180 and 1260. Possibly the irrigated fields produced better and more reliable harvests, and, from Figure 2, after 1180 there appears to be an increase in rain until about 1250. If overall conditions did improve during this time, perhaps the Commoner’s faith in the wisdom and power of the Nobles over the weather, as well as the overall Chacoan System may also have been restored. That is until around 1275, when the droughts and precipitous global cooling recommenced in earnest, lasting until 1300. During this time period extreme violence, now more in the form of warfare, is again found in the Chacoan World between 1260 and 1280 (Kohler, et.al., 2014), with communities massing together on defensible mesa tops or within cliff dwellings for safety. The chaos of these times was systemic with the eventual result of complete cultural collapse with both Nobles and Commoners alike abandoning the Four Corners area en masse by the tens of thousands. The Chaco Phenomenon was over.

During the period of Collapse and Abandonment of the Chaco/Aztec System around 1275-1280, and perhaps earlier during the move from Chaco to Aztec, Lekson (2015) contends that numerous Noble families headed due south along what he terms the Chaco Meridian where they would resume noble opportunities in the new emerging capital city of Paquime in Casas Grandes, Chihuahua, Mexico, 670 km (400 miles) south of Chaco Canyon. The evidence for a Chaco/Aztec/Paquime connection is a fascinating story in itself, and is the primary focus of Lekson’s 2015 book The Chaco Meridian.

During those turbulent times, the Commoners that fled or survived during the various Noble inflicted traumas during the latter years of Chaco, and the later warfare during the final collapse of Aztec, either migrated to points unknown or stayed in the general area to found new, more egalitarian, farming pueblos both to the west, south, and east of the Chaco/Aztec region, as represented by the Hopi, Zuni, and Acoma Pueblos of today.

A POSSIBLE UNWRAPPING OF SOME OF THE MYSTERIES OF THE GILA CLIFF DWELLINGS IN LIGHT OF THE RISE AND FALL OF THE CHACO PHENOMENON

The above summary of the Rise and Fall of the Chaco Phenomenon is a mixture of well-researched and documented archaeological fact, plus a heavy dose of follow-the-dots type reasoned conclusions and assumptions, as well as a little unabashed speculation. Quite often in archaeology, as in geology, the hard data that is found often raises more questions than it answers. And certainly this is the case with the Gila Cliff Dwellings. While there are important evidencial facts and clues from the Chaco Phenomenon which can shed some new light on the Key Questions posed in Part 1 of this blog regarding the People of the Gila Cliff Dwellings, the new evidence, indeed, raises a whole new set of questions.

The Key Questions Regarding the Gila Cliff Dwellers

Who were these Cliff Dwellers anyway and what were they like?

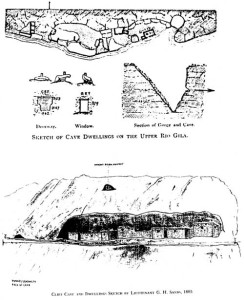

Convincing evidence, as summarized in this blog, supports the argument that the Gila Cliff Dwellers were Chacoan Nobles. Primary evidence for this fact is the abundance of prestige-economy marine shell jewelry, 26 macaw feathers, and 1 macaw skull; plus the architectural evidence in the commanding presence of a T-shaped door that for all intents and purposes says “We Are Chacoan”. If they were Nobles, then the evidence from Chaco also strongly suggests that they probably did not build the dwellings, farm the fields near the TJ Ruins, gather wild edible plants, or cook their own meals … Chacoan Nobles didn’t do such things; they had commoners or slaves to do this work.

Where did they come from?

Because the construction date of the Cliff Dwellings (1276-1287) as known from tree ring dating of the roofing vigas, corresponds exactly to the time of the Great Drought of 1275-1300 and the final Collapse of the Chacoan social and political system, it is considered most probable that the Gila Cliff Dwellers came either from an Outlier to the north or possibly from Aztec. Because of the abundance of Tularosa Phase pottery found in the Cliff Dwellings, the type locality for which is the Aragon/Reserve area 50 miles to the north, a southern Outlier would seem more likely than further north in Aztec. Although, a related fact is that Chacoan Nobles did not make their own pottery, so they could have come from Aztec and simply used locally made pottery, either imported from the Aragon/Reserve area or possibly made 1-1/2 miles away at the TJ Ruin.

Why did they come, and why did they choose to stay in dark, cold caves as opposed to the large TJ Ruin?

Based on the construction dates and suggested short-term occupation of the Gila Cliff Dwellings relative to the current understanding of the time and events of the final collapse of the Choacan social and political system, it is highly likely that the Nobles were fleeing the “Troubles up North” as suggested in Part 1 of this blog. As discussed above, Lekson (2015) makes a strong case that following the final collapse of the Chacoan System many of the Noble families left their failing system of increasingly oppressive rule over the Commoners, and moved south to Paguime at Casas Grandes, Chihuahua, Mexico.

Were there people living in the TJ Ruin site at the time, and if so what was their relationship with the Cliff Dwellers?

Only the formal excavation of the TJ Ruin could possibly provide definitive answers to this question. However, the strong evidence that the Gila Cliff Dwellers were Chacoan Nobles, and that Chacoan Nobles didn’t construct buildings, or farm the fields, etc., does support the possibility that the TJ Ruin was inhabited at the time of the Dwellings by someone, perhaps a reduced holdover population remaining from TJ Ruin’s height of occupation, or alternately a group of loyal Commoners of various types who accompanied the Nobles on their flight from the Chaco World who could have taken up residence in the abandoned TJ pueblos and farmed the adjacent fields.

Why did they stay such a short time? (as suggested by lack of adult burials, lack of trash, lack of building modifications and additions), and Why did they leave?

The presence of Noble prestige economy goods such as abundant marine shell jewelry, macaw feathers, and the skull of at least one live macaw being left behind could suggest a very sudden rather than a planned departure from the Cliff Dwellings, as these exotic objects and the T-shaped doors were the only proof of their Noble status. Did the “Troubles Up North” somehow catch up with them, forcing them to flee in the middle of the night? Also, as mentioned in Part 1 of this blog, large caches of stored maize in the form of cobs, were also found in the Cliff Dwellings, also suggesting an unanticipated departure. This sort of complete abandonment of personal goods and stored foodstuffs was a common archaeological discovery in the Aztec area, particularly in the Cliff Dwellings, during the last decades of the Collapse and Abandonment.

Where did they go?

Recent archaeological research at the Paguime Ruins and the surrounding Casas Grande area in Mexico, and the San Juan Basin area surrounding Aztec, have strengthened Lekson’s proposed connection between the collapse of the Chaco/Aztec Culture and the sudden emergence of the Paquime Culture. New analyses regarding the beginning of construction for the initial major buildings at Paquime yield dates of 1250 to 1300, which corresponds to the final collapse at Chaco and Aztec. Looking past the initial observation that the 4- to 5-story Paquime buildings are constructed of adobe while those at Chaco and Aztec are of stacked stone masonry, many architectural similarities between the two areas exist, such as the iconic T-shaped doors of Chaco and Aztec. Also, Paquime was very much involved with the prestige economy, and over time became a major center for the production, manufacture, and distribution of prestige economy goods, such as live macaws and macaw feathers, marine shell jewelry, copper bells, pottery, etc.

Perhaps the final collapse and abandonment of the Chacoan/AztecSystem is best summed up by Lekson (2015), when, after describing how the remaining Commoners moved east and west beyond the Nobles reach to reinvent themselves as communal, egalitarian farming Pueblos, he concludes by saying “scores of noble families, after many generations ruling, wanted nothing of the new egalitarian ethos. They sought new commoners to rule – that was their job on earth. There were no takers in the north, so they moved south – along the meridian.”

Research on ancient north–south trade routes used by prehistoric Native Americans indicates several possible routes leading south along the Meridian that the migrating/fleeing Nobles might have taken between Aztec and Chaco and Paquime. It is quite possible that one of them passed through TJ Ruin and the Gila Cliff Dwellings.

REFERENCES:

1. Lekson, S.H., 2015, The Chaco Meridian. Rowman & Littlefield, 257 pp.,

2. Turner, C., and Turner, 1999, Man Corn: Cannibalism and Violence in the Prehistoric American Southwest.The University of Utah Press, 547 pages

3. Ljungqvist, F.C, 2010: A New Reconstruction of Temperature Variability in the Extra-Tropical Northern hemisphere During the Last Two Millennia. Geografiska Annaler, 92 A (3): pp.339-351

4. Grissino-Mayer, Henri D., 1996, A 2,129 Year Reconstruction of Precipitation for Northwestern New Mexico, USA, Tree Rings, Environment and Humanity, ed. J. S. Dean, D. M. Meko and T.W. Swetnam, Radiocarbon, pp. 191-204

5. Kohler, T.A. et al., 2015, The Better Angels of Their Nature: Declining Violence Through Time Among Prehispanic Farmers of the Pueblo Southwest, American Antiquity 79(3), 2014, pp. 444-464